Every one of us knows, in our heart of hearts, that we’re geniuses. If only we didn’t have the distractions of life, we could be brilliant at [insert discipline here].

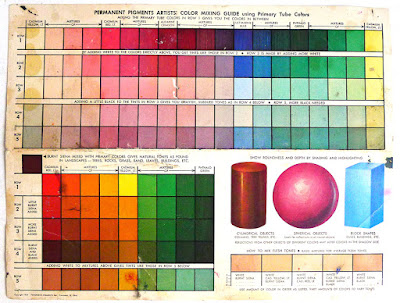

Yesterday, my student Terrie told our Zoom class about something she’d read in a composition book. “Wow, the things I could learn if I actually read the books on my shelves instead of just looking at the pictures,” I joked, because I have the same book too.

It turns out that she was describing the ‘conscious competence’ learning model. It posits the following phases in learning a new skill:

Unconscious incompetence—the student doesn’t know what they don’t know;

Conscious incompetence—the student has figured out that they don’t know, and is making the mistakes necessary to learn;

Conscious competence—the student has figured out how to do it, but the steps require a lot of concentration;

Unconscious competence—the skill is second nature.

|

Every painting teacher has had the experience of the student who responds to every suggestion or criticism with ‘yes, but.” I was once that student myself, so it’s fairly easy for me to overlook, although it does take up valuable class time.

However, over twenty years of teaching, I’ve learned that if they don’t drop that attitude, they’ll take one session and then not come back. They’ve built up a protective wall around their self-image. Challenging that is too uncomfortable.

|

Every one of us knows, in our heart of hearts, that we’re geniuses. If only we didn’t have the distractions of life, we could be brilliant at [insert discipline here]. However, it’s one thing to doodle, but another thing to drop the excuses and really challenge ourselves. All our shortcomings are revealed.

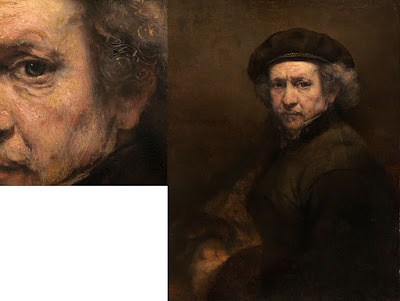

Going from dreamer to practitioner is an immensely humbling experience. That’s why—I think—so many truly-skilled artists are actually very modest people.

The instruction-resistant student can still make progress. One can teach oneself to paint with videos and books. However, that attitude is an impediment to learning, so they’ll linger in the phase of unconscious incompetence much longer than is necessary. I think I spent twenty years there, myself.

|

|

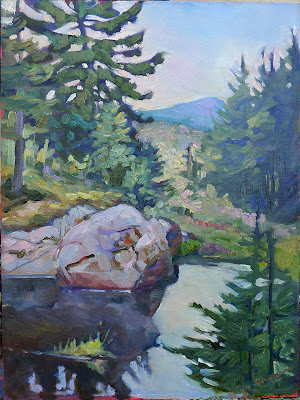

Fog over Whiteface Mountain, 11X14, oil on archival canvasboard, available |

Mercifully, most of my students start somewhere in the second phase—they’re completely aware of how little they know, and how much they have to learn.

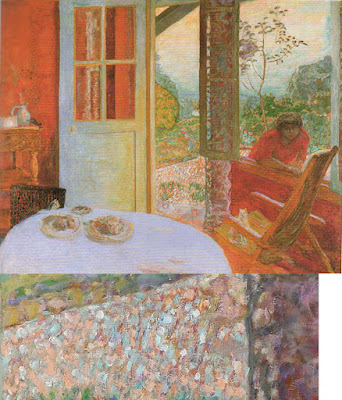

Yesterday I watched Jennifer paint a lovely red carnation in a bud vase. When she started my classes, she was doing delicate botanicals in watercolor; now she’s doing energetic, well-composed paintings across three media. She can prowl around all kinds of subjects with authority.

She’s one of my students who are in the third phase. She knows the steps and she’s refining her technique. I’m really there to stop these students from wandering off into the scrub and losing their way.

And then they’ll graduate to the last phase. These are the students I don’t mind losing, because I’m watching them fade out of my classes and into the world of their own mastery.