Poppy discovered the joys of manure, but my feet were thoroughly blistered.

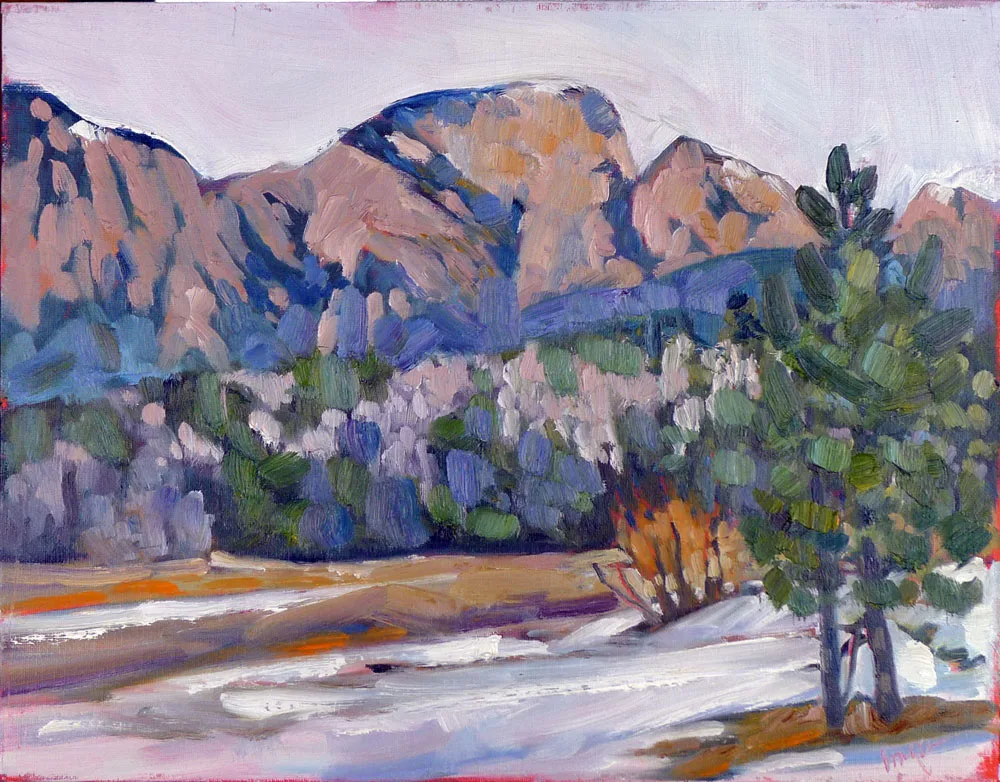

|

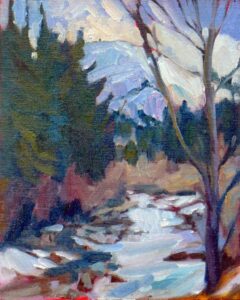

| The beautiful Northumbrian landscape. |

This is what I’d call ‘hill-walking’ but my friend Kenny—who was raised on the shores of Loch Linnhe, just a hop, skip and a jump from Ben Nevis—thinks of as a doddle. Shortly after leaving the Tyne at Newburn, we started the long slog up to Heddon-on-the-Wall. There is no urban sprawl here—just long agricultural vistas and Constable skies.

These small Northumbrian villages are Cotswold-beautiful, built of golden-brown stone and perched on high hills with magnificent vistas in every direction. Still, all the beauty in the world doesn’t prevent one from being parched and in need of a pee by midmorning. There was a public house but it seemed a bit early, even for me.

|

| The ever-polite British have deferred the 1900th birthday celebrations for the wall until September, so as to not take away from the Queen's Jubilee. |

“Look for a Methodist church,” said Alison, and she was right. They had a bathroom, and they offered us coffee, tea, and cheese scones. We had a lovely sit in their garden before we went to look at our first section of unreconstructed wall. Thank you, lovely Methodists!

From there we walked a section of military road planned by Field Marshal George Wade following his inability to move artillery and troops cross-country in pursuit of Bonnie Prince Charlie. The old wall was torn out and used as the base for the highway. The British were pretty sick of the Jacobites by that point.

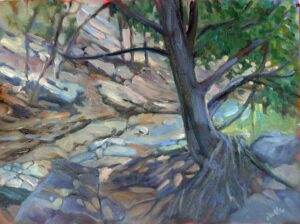

|

| Our first glimpse of the wall since Wallsend. |

After crossing the A69, we dropped down into a peaceful meadow where Poppy discovered the joys of cow dung. Poppy is a well-bred lass from Edinburgh but that didn’t stop her from rolling ecstatically. Fifteen minutes and a package of baby wipes later, we’d fairly evenly distributed the manure among our human persons, with only a moderate amount left on the dog.

Rural England is crisscrossed by public rights-of-way, but they’re shared with livestock. I don’t mind cows; they’re generally leery of people. Horses so far have been behind fences; that’s good as they’re far too canny to be trusted with daypacks.

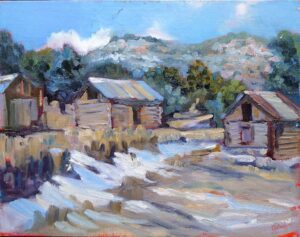

|

| Rudchester Farm. |

At Rudchester, we crossed a sheepfold, the site of the fourth fort along the Wall, Vindobala. The only reminder of its existence was the unnatural flatness of the farmyard—and the ancient stone walls, undoubtably made of reclaimed stone. As we gathered to read the explanatory sign, Poppy found sheep manure and joyfully worked it with her muzzle.

I am an assiduous hiker who does 4.5 miles up Beech Hill every morning before breakfast. I’d hoped that would prepare me for this walk, but by midafternoon, my own poor dogs were blistered. They were sliding forward with every downward step. At lunch, Martha cleverly relaced my hiking shoes for me, but the damage was done. I limped the remaining distance.

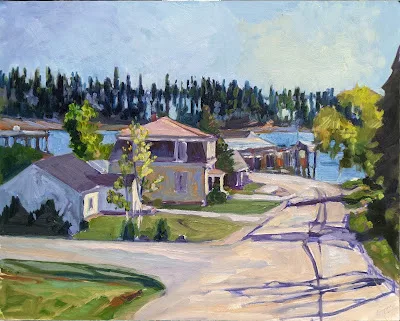

|

| The path is very well marked, and surprisingly busy. |

Kenny is very kind. For the last four miles, he promised me that there was a pub just another half mile along.

It worked.