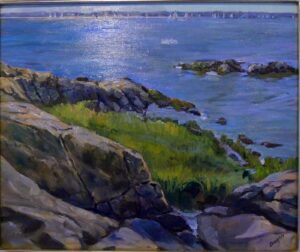

Here in the northeast, we’re seeing the first intimations of autumn-the earliest scarlet leaves starting to drop on the forest floor, staghorn sumac sporting red velvety fruit, goldenrod and fireweed popping up in unmowed fields.

There is a subtle difference in the color of leaves. In a dry summer, that’s exacerbated, but by the third week in August, there will always be maples sporting a halo of red, and the birches have tempered into olive-green.

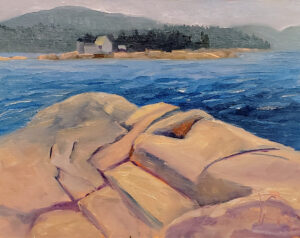

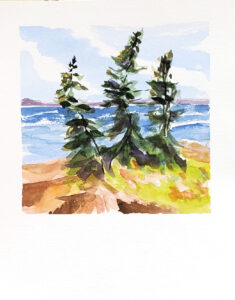

Even evergreens change color with the seasons. New growth is a very different color from the dormant needles of midwinter.

I’m leaving this morning to teach in the Adirondacks. It’s even cooler in Paul Smiths, New York (41 F as I write this) then here in coastal Maine. That should kick the swamp maples into their absurd fuchsia finery. It also means I’m going to repack my suitcase with warmer clothes before I take off.

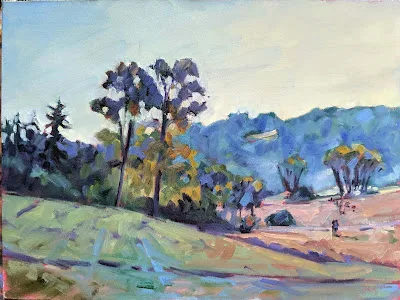

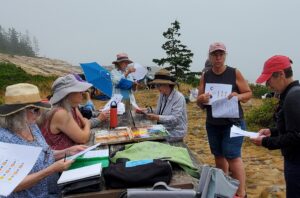

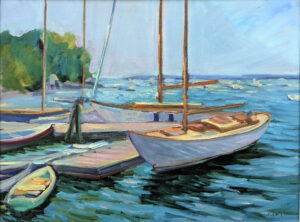

We’ll be concentrating on the shift in greens. My students are familiar with all the exercises I give them to mix greens, because doing it accurately makes all the difference to eastern landscape painting. (The inverse, the ability to mix reds, is equally important in New Mexico and Arizona.)

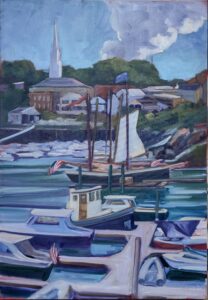

Even in the height of autumn in leaf-peeping country, green remains the predominant color. But it will not be the same green as in May or July. These subtle changes will ground a painting with a sense of season, as well as a sense of place.

I take great joy in weather, even when it’s hot or bitterly cold. I love being outside, feeling air on my skin. Recently, I’ve found my enjoyment is sometimes blunted by the endless, repetitive news cycle of catastrophic or record-breaking heat waves or winter storms. (I’m from Buffalo. I’ll see your snowstorm and raise you a blizzard.)

This is not to deny that the climate is changing-it is, and that will continue. But most weather records are relatively recent things, meaning it’s not hard to get windier, colder, hotter, or wetter than what we’ve already measured.

Poppy Balser and I were both raised on family farms. During the last heat wave we talked about haying, as it even harder than painting in beating sun. Putting up hay the old-fashioned way, with square bales, is the essence of summer heat. It may not be particularly enjoyable to stand in a hay loft, drenched in sweat, covered by infinitely small and scratchy particles of hay dust, sneezing. But it is memorable, and I’m glad I grew up doing it. In fact, I’d do it again if they’d just make bales that weighed fifteen, rather than fifty, pounds.

Weather is far more pleasant if you experience it. It’s still hot where you live? Go get an ice-cream cone and enjoy it. Autumn is really just around the corner.