I have three students whom I’ll call A, B and C.

A and B are both very accomplished. C is earlier in the cycle but has good instincts and is working very hard to close the gap. It’s paying off.

I got a sad text from C that read in part, “I am really not at the level of the others in our class.”

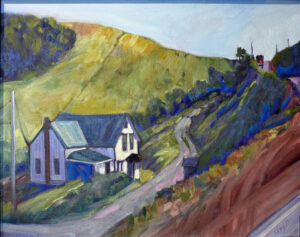

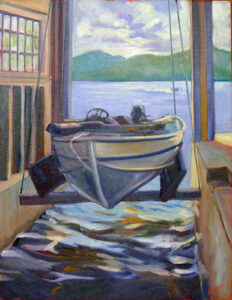

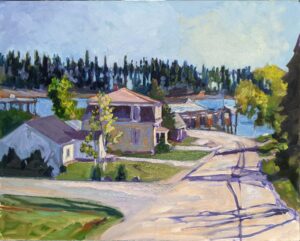

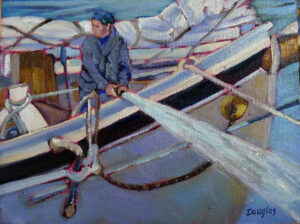

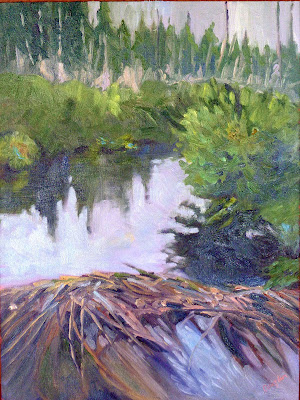

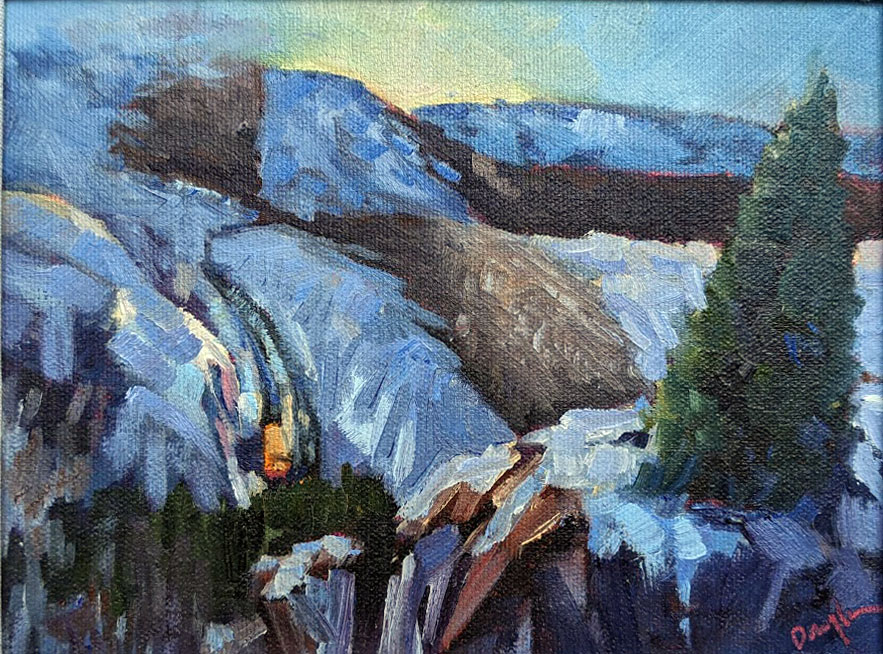

C is a perfectionist, and that occludes her vision. (That’s, sadly, a common problem among painters who were very successful in their first careers.) C can’t see how energetic her brushwork is, how controlled her color is, or how beautifully she composes. All she sees are deficiencies.

“Are you kidding?” I responded. “A and B are both painting at a professional level, but the rest of the class is on the same level as you.” I didn’t say that to make her feel better, but because it’s true.

Shortly thereafter, I got an email from B. “A is killing me,” she lamented. “I so want to paint like her. Wow, is she good.”

I haven’t heard from A yet, but I wouldn’t be surprised if she emailed me to tell me how much she wished she could paint like someone else.

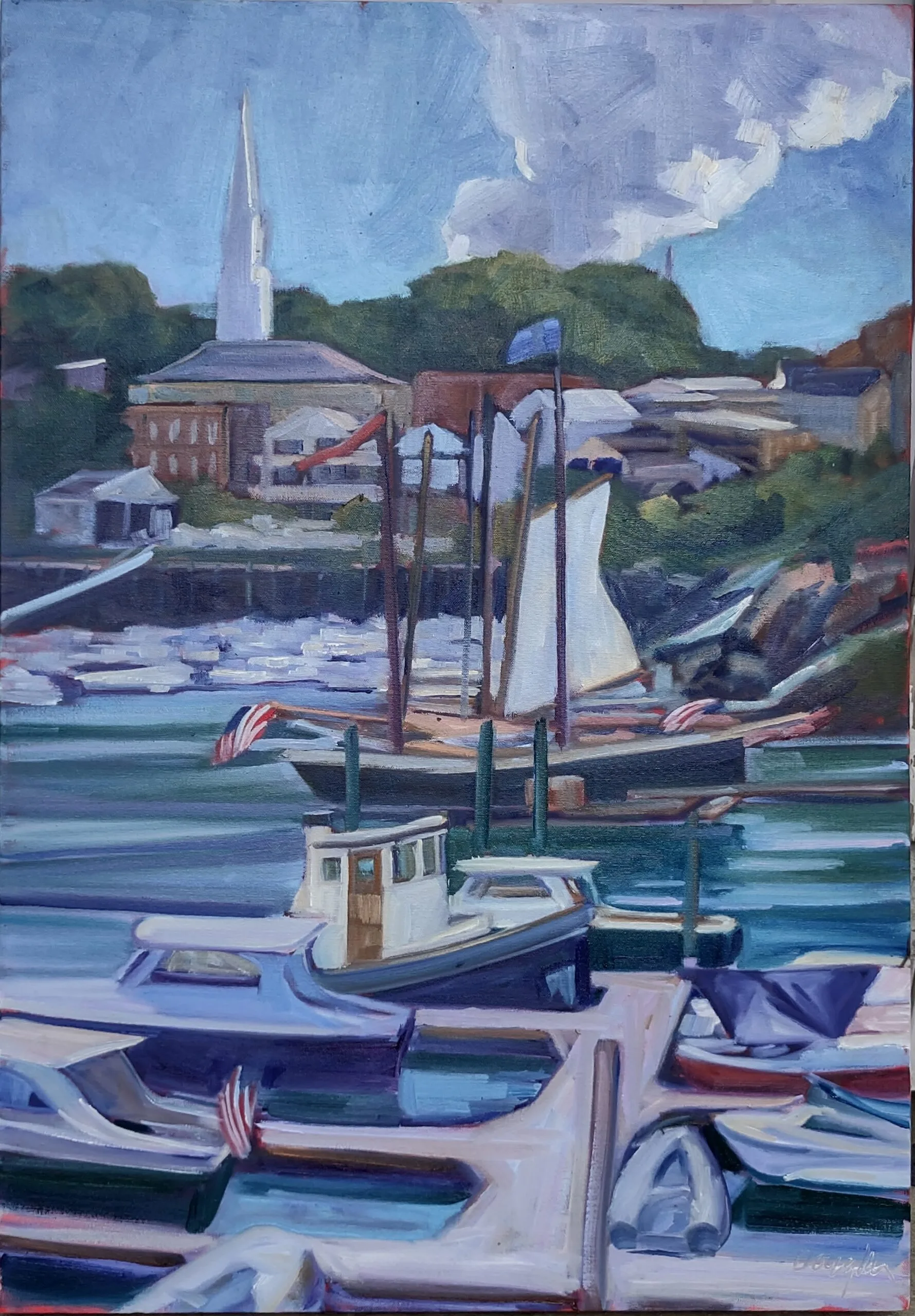

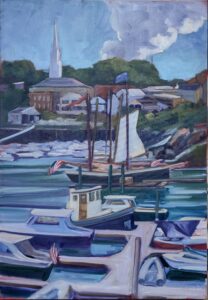

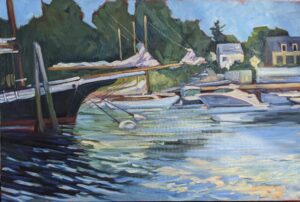

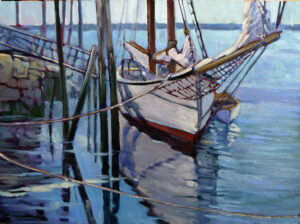

I love painting with Eric Jacobsen and Ken DeWaard, but there are days when I want to throw my brushes in the harbor when we’re done. Eric’s brushwork is lyrical; Ken’s drafting is exquisite. I peek at their work and see only my own deficiencies in comparison.

I was once at an event where I felt totally outclassed. I know it makes no rational sense, but I’d convinced myself I’d somehow gotten in by mistake. “I feel like I’m surrounded by the big boys,” I whined at Eric.

“You are one of ‘the big boys,’” he told me. “You’re here because they chose you, and they chose you because they want you.” From that moment I was able to relax and do my job properly. Insecurity, anxiety, and envy were robbing me of my confidence. Without that, what could I possibly achieve that was fluid, relaxed and compelling?

Envy is hard work’s evil twin

I’m not telling you this because I want to add ‘envy’ to your reasons to beat yourself up. We all feel envious at times. I bet some sense of inferiority stretches back from painter to painter all the way to the anonymous artist who first chalked on a cave wall.

“Ambitious men are more envious than those who are not,” Aristotle wrote in his Rhetoric, about 2400 years ago. “Indeed, generally, those who aim at a reputation for anything are envious on that particular point.” To excel, you must really want success, and envy is hard work’s evil twin.

Envy is an emotion, so by definition it’s irrational. That doesn’t mean we must be slaves to it. Eric dispelled my terrible state of mind with a few well-chosen words. I’ve been able to repeat them to myself as needed, and so can you.

Why do we deflect praise and take criticism to heart?

One day a fellow dog-walker said to me, “You look fabulous. You’ve really lost a lot of weight.”

“Oh, it’s just my leggings,” I said.

“Wrong answer,” she laughed. “Just say ‘thank you.’”

We deflect praise even when it’s true, but we take criticism to heart despite it being absurd. That’s especially true when it’s our jaundiced, ornery liar of a self who’s doing the speaking. Painting is uniquely and painfully personal. To excel, we must ignore those whispers of comparison and self-doubt. It’s really as simple as catching yourself in the self-doubt cycle and saying, “STFU, Self!”