I give new students a protocol sheet. On one side it lists the steps for a good oil painting, on the other side, the steps for a good watercolor. (Acrylic painters can follow the oil painters’ lead.) Then I tell them they no longer need me, and laugh.

Last year, I realized that there was a step missing on the watercolor side, a step that seemed so basic that I had failed to include it. It was to wet the paints on the palette before starting painting. I expected that everyone knew that. Silly me, because it’s critical for clean, bright color.

Watercolor can be purchased in pans or tubes. If the latter (which I far prefer), it’s generally squeezed into a palette and allowed to dry. (There are a few painters out there who squeeze out new watercolors every time they work; that’s an expensive and unnecessary practice.) In either case, the paint needs to be activated. That means wetting it down to approximate its consistency out of the tube.

The easiest way to do this is with a small spray bottle; you can also use a syringe or drop (clean) water from a brush. It should be done 10-15 minutes before you start painting, and might need to be redone as you work, depending on environmental conditions.

Before activating your paints, make sure they’re clean. Any color that’s migrated into another pan is best removed when the underlying color is dry. You can do this very easily with a damp brush. And if you didn’t clean your mixing wells earlier, this is a good time to do it.

How wet should your paints be? Wetter than you might imagine. You need to lay a solid film of water over the top of the paints and let it soak down into the pigments. That takes more than a few seconds. If you go several days between painting sessions, expect it to take at least fifteen minutes.

The proof is in the pudding

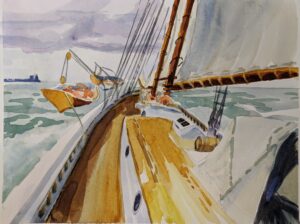

My old pal, watercolorist Stu Chait paints deep, intense hues in his abstract paintings. He gets them by working with suspensions of paint in little square cups. Bruce McMillan, master of clean color, paints on a big butcher’s tray with paint cups around the center.

The best way to achieve a prissy, old-lady look in watercolor is to start with dry paints. Even a wet brush can’t pick up enough pigment to give saturated color. To compensate, the artist starts to glaze colors, over and over. Eventually he has something so delicate, so refined, so dull, that it looks like it was done by a minor British noble’s maiden aunt.

Watercolor is shockingly durable. I have a palette given to me by a retired artist. It contains the paints she used back in art school in the 1970s. They awaken with a sheer misting of water. This is one reason for the perpetual love affair of painters with watercolors-they’re patient. You can slip them in a backpack and ignore them for months between uses.

One more thing

There are a few slots open in my critique class, starting tonight.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

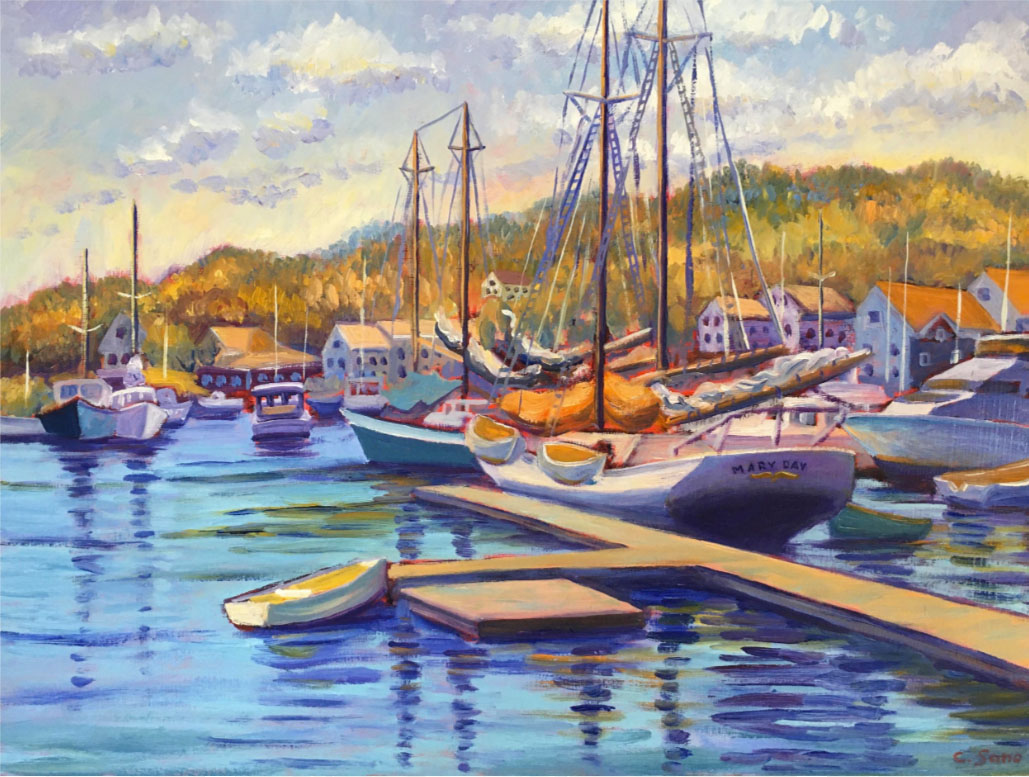

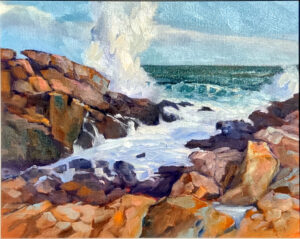

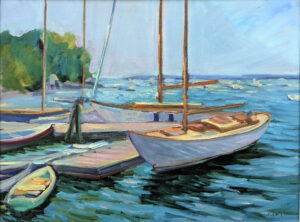

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

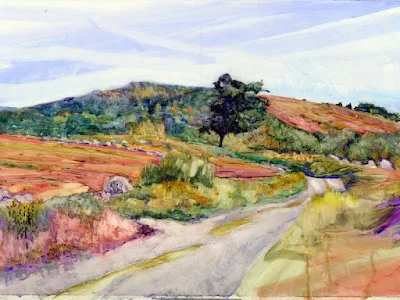

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

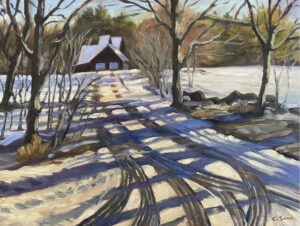

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.