I had an entertaining text exchange with an emerging painter yesterday. “We spend too much money on better paper, fancy brushes, and teaching videos,” he mused. “We think we can buy our way into good results. But it all comes down to spending time painting. One must actually apply paint to paper to understand the lessons, to get them into one’s head.”

A few moments passed and he added, “Of course, that’s very dangerous if you’re painting with other people with all the same bad habits as you.”

Therein lies the conundrum. Yes, you need to paint — lots, fast and furious — to improve. But you also need to understand the fundamentals, and it helps to have good materials. It’s like playing the piano. Both practice and instruction are critical, but you’ll enjoy it a lot more if your piano holds a tune.

I have two sets of watercolor brushes. The first are high-end, large brushes that I use for ‘important’ work. The others are mid-range Princeton Neptunes. These days, most of my watercolor painting is pootling around in my sketchbook, so of course I grab the Neptunes. It figures that I’ve gotten better with them than with my fancier brushes.

I once told my Zoom class that one could paint in oils with a stick, and that my ratty, half-hardened brushes proved it. Instead of taking that lesson to heart, they bought me new brushes (which moves me every time I think of it). While it’s quite possible to paint in oils with a stick, or even a palette knife, it is lovelier to paint with my treasured new brushes.

Palomino Blackwing pencils are going around my students like COVID right now. “Are you made of money?” I ask them, tongue in cheek. I’d order them too if my business partner didn’t have a death grip on our checkbook. Sometimes it’s just fun to have lovely things.

More fun, I’m afraid, than buckling down and doing the hard slog. But, of course, the hard slog pays off in ways that shopping never can.

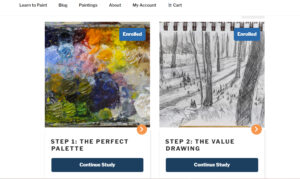

Last month I introduced The Value Drawing, an interactive class that discusses how to make an effective value drawing. Today I’m introducing The Correct Composition, an even weightier tome. The Perfect Palette came out earlier this year.

Laura and I have been releasing them as we finish them, with the idea that we’d market them as a set when the whole Seven Protocols for Successful Oil Painters is finished. Today I realized that was unfair to my followers. If you buy the whole series at one time, you’re going to rush through it, whereas if you have it episode by episode, you’ll take the time to do the exercises and quizzes, and above all, “actually apply paint to paper to understand the lessons, to get them into one’s head,” as my correspondent wrote.

The Value Drawing is closely related to The Correct Composition, so if you haven’t done that one, you might want to do them both now. Meanwhile, I’ll continue to work on the next step, which is The Essential Grisaille.

To put it in perspective, one of these classes is the discount price of a 9/12 Arches Watercolor block. The three I have done so far total the same amount as an 18/24 Arches Watercolor block. I’d never dis the value of a fancy new watercolor block; I adore them. However, I know that knowledge will improve your painting far faster than better paper, or brushes, or even those luscious pencils.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

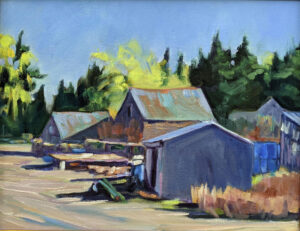

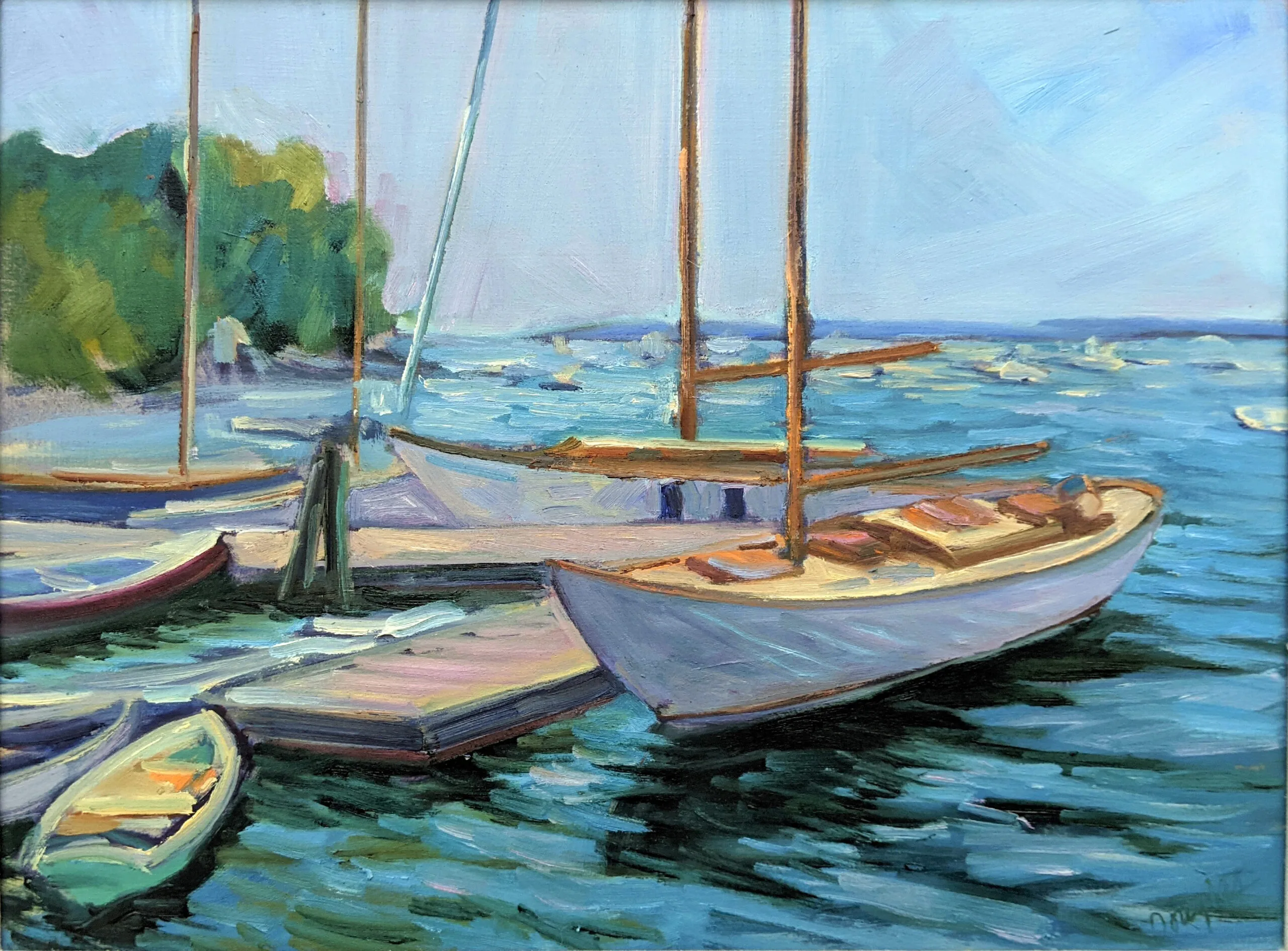

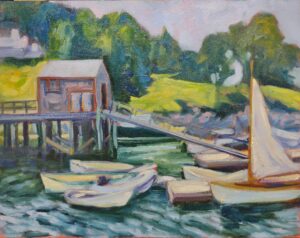

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.