I have a tome somewhere that ‘proves’ that blue landscapes are the buying public’s favorite. Apparently, they weren’t the only social scientists who addressed the question. “Some Russian consortium declared after ‘much study’ that a 12×16 with a water view, a dog and something red will outsell all others,” Björn Runquist told me. “How’s that for precision?”

Natalia Andreeva read the exact opposite thing. “When I was a student and read way more books, one of them said that people do not like blue paintings; green or red are the colors to go with. Most importantly the work should carry a positive cheerful message. Any grim or highly-edgy subject is good for being noticed but not for selling.”

I asked ChatGPT, which told me that neutrals and earth tones are popular. That’s so last year. So, I moved on and asked a group of professional artists what, in their experience, sells. I’ve edited their responses for length.

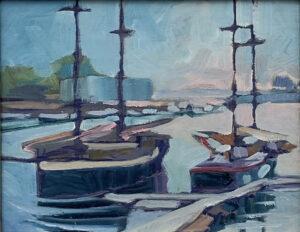

Colin Page: Some galleries tell me rules for what subjects they think don’t sell: snow scenes, boats out of the water, paintings with too much yellow. I suppose landscapes/seascapes have the broadest appeal, but I don’t find it matters for sales potential if the painting is good enough.

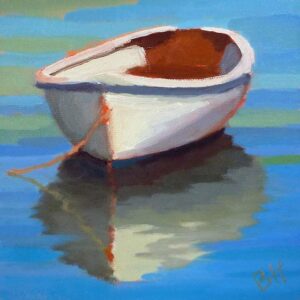

Bobbi Heath: It must have meaning for them. Thus, the popularity of pet portraits. Since I mostly sell landscapes, and usually the sun shines in my paintings, I buy the hypothesis about blue. But maybe it’s really about sky and water. My most popular paintings are of boats. But boats are close to my heart, so perhaps I paint them with more feeling.

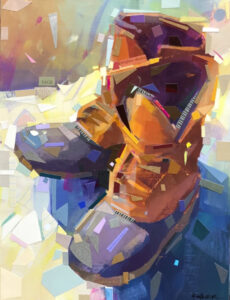

Ryan Kohler: I have subjects to paint that are in my wheelhouse, almost like bread-and-butter images: boots, boats, NYC, landscape, architecture, and critters. But then there are my ‘fun’ categories too that don’t really sell well (or at all) but I still love doing.

On top of trying to navigate those murky waters, I also have the added non-benefit of switching mediums regularly. I’ve sold plenty of paintings throughout all phases. I don’t think that many folks walk into a gallery looking for an acrylic painting, or a watercolor, or a linocut print. I think they head into a gallery looking for work that speaks to them. It’s probably more about wonder and excitement than boring stuff like media and price.

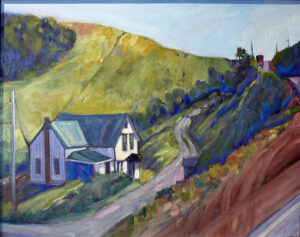

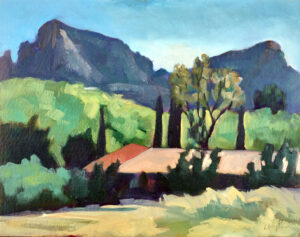

Casey Cheuvront: Out here in AZ, paintings of cactus will outsell sailboats. A painting of an iconic Prescott bar will sell in Prescott. Paintings of the yuppie barrio buildings will sell in Tucson. My friend Jan, who lives in northern CA, sells mostly seascapes.

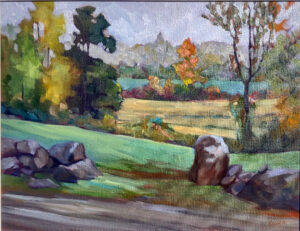

In the past year I have sold landscapes, animal and still life, many plein air pieces, several studio works, a number of small paintings, and large paintings. Most of these were oil paintings, some were watercolor/ink. They’ve been various size ratios.

I find myself constantly surprised by what sells and what doesn’t. But good work sells, eventually. Of course, price has something to do with it. Another painter once told me “The perfect price is the intersection of what your collectors are willing to pay and what you are willing to take to let it go.”

Poppy Balser: Looking through my paintings that have sold over the last year, they’ve been mostly boats, beach scenes, harbour scenes and a few landscapes. But that is also what I paint the most of, because these are the subjects I most enjoy painting.

In Camden, boats sell well. In the gallery in our main agricultural region (the Annapolis valley in Nova Scotia) landscapes, farming scenes, and Bay of Fundy coastal scenes do well. In Florida beach scenes do well.

Often the ones that sell quickly and directly are often the ones I have best managed to tell a bit of a story about. And a lot of mine that sell are predominantly blue, because, well, ocean.

Natalia Andreeva: People buy what speaks to them. They may see something in your work that you did not even intend, so painting what speaks to me makes more sense than chasing mirages. There is no point to guessing; just keep working and keep looking for new venues (easier to say then do, but it’s the right way to do it).

Mary Byrom: My big rule of thumb is I sell everything I show that is $600 and under. I sell all the small paintings that I show. All of them are landscapes, seascapes, or townscapes. Any and all landscape subjects. Oil, gouache, acrylic and watercolor. Plein air, memory, imagination, all types.

I sell some large paintings directly to collectors. I used to sell them in one gallery that closed due to health problems. I have not found another relationship like that gallery. I was in 13 galleries. I cut back steadily to two galleries and my studio.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.