This post first appeared in 2021, and has been edited to respond to questions from my Berkshire workshop students.

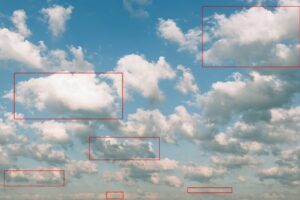

Clouds are not flat. The same perspective rules that apply to objects on the ground also apply to objects in the air. We are sometimes misled about that because clouds that appear to be almost overhead are, in fact, a long distance away.

I’ve alluded before to two-point perspective. I’ve never gotten too specific because it’s a great theoretical concept but a lousy way to draw. Today I’ll explain it, but it’s not how I want you to draw clouds. It’s just to understand them.

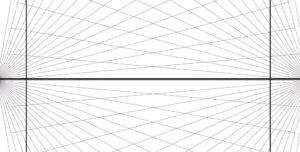

Draw a horizontal line somewhere near the middle of your paper. This horizon line represents the height of your eyeballs. Put dots on the far left and far right ends of this line, at the edges of your paper. These are your vanishing points.

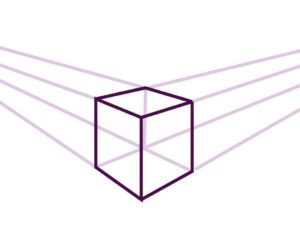

All objects in your drawing must be fitted to rays coming from those points. A cube is the simplest form of this. Start with a vertical line; that’s the front corner of your block. It can be anywhere on your picture. Bound it by extending ray lines back to the vanishing points. Make your first block transparent, just so you can see how the rays cross in the back. This is the fundamental building block of perspective drawing, and everything else derives from it. You can add architectural flourishes using the rules I gave for drawing windows and doors that fit.

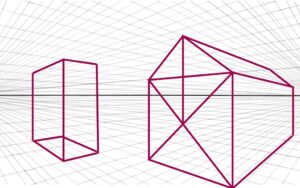

I’ve included a simple landscape perspective here, omitting some of the backside lines for the sake of clarity.

As a practical tool, two-point perspective breaks down quickly. In reality, those vanishing points are infinitely distant from you. But it’s hard to align a ruler to an infinitely-distant point, so we draw finite points at the edges of our paper. They throw the whole drawing into a fake exaggeration of perspective. That’s why I started with a grid where the vanishing points were off the paper. It doesn’t fix the problem, but it makes it less obvious.

(There is also three-point perspective, which gives us an ant’s view of things, and four-point perspective, which gives a fish-eye distortion reminiscent of mid-century comic book art. And there are even more complex perspective schemes. At that point, you’ve left painting and entered a fantastical world of technical drawing.)

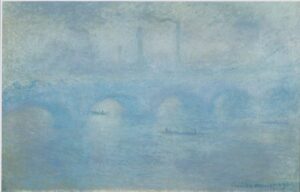

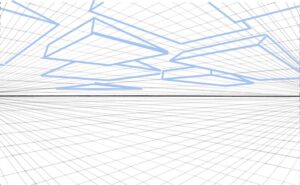

Still, two-point perspective is useful for understanding clouds. Clouds follow the rules of perspective, being smaller, flatter and less distinct the farther they are from the viewer. The difference is that the vanishing point is below the object, rather than above as with terrestrial objects.

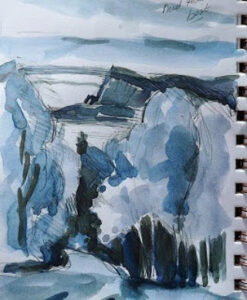

Cumulus clouds have flat bases and fluffy tops, and they tend to run in patterns across the sky. I’ve rendered them as slabs, using the same basic perspective rules as I would for a house. They may be far more fantastical in shape, but they obey this same basic rule of design.

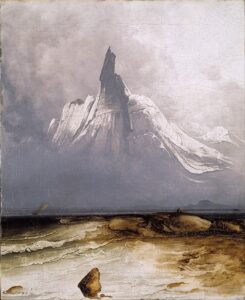

Clouds form where there’s a temperature change in the atmosphere. That means a flight of cumulus clouds or a mackerel sky will all have their bottoms at the same altitude, i.e. the same plane. However, there can be more than one cloud formation mucking around up there. That’s particularly true where there’s a big, scenic object like the ocean or a mountain in your vista. These have a way of interfering with the orderly patterns of clouds.

I don’t expect you to go outside and draw clouds using a perspective grid. In fact, that would be completely wrong. This post is to help you understand the concept before you tackle the subject. Then you’ll be more likely to see clouds marching across the sky in volume, rather than as puffy white shapes pasted on the surface of your painting.

Instead, I want you to observe the plane where clouds are forming, and how you’re looking up at the bottom of it. Note the real angles of the patterns they make. You use your pencil to figure this out. Line it up with the pattern of the clouds and then mark that angle on your paper, just as you do with any object you draw. Just make sure you keep the pencil square to an imaginary glass window, as you do with the pencil and thumb method of measuring.

Drawing clouds-like everything else-is all about measuring angles and distances. But the nifty thing about clouds is that in two minutes they’re totally different. Sneaky little devils.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

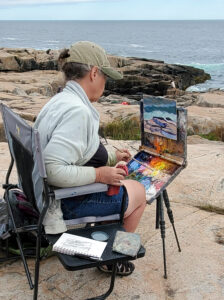

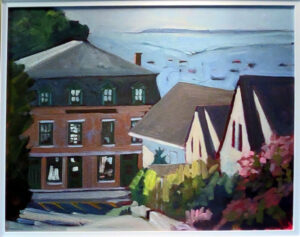

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.