On the second day of my Rockport Immersive workshop, I took my students to the Farnsworth Art Museum to look at landscape paintings. As you might imagine, the Wyeth family are featured prominently. I want to say up front that I admire NC, Andrew, and especially Jamie Wyeth, who, in addition to having his forebears’ amazing chops, can often make me laugh out loud.

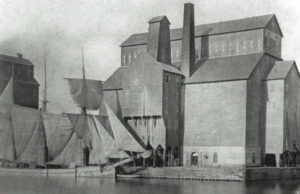

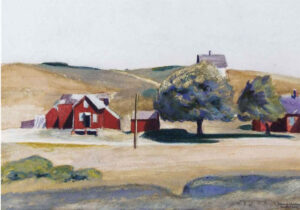

A current exhibition documents Andrew Wyeth’s relationship with siblings Alvaro and Anna Christina Olson and their ramshackle saltwater farm in Cushing, ME.

Andrew Wyeth spent time at the Olson House from 1938 until immediately after the Olson’s deaths in December, 1967 and January, 1968. Christina was the more famous Olson, as she was the subject for Wyeth’s Christina’s World. A victim of a degenerative muscular disorder, she lived most of her life as an invalid. At the age of 53, she lost her ability to stand, so she crawled everywhere. (She chose to not use a wheelchair.)

The Wyeths summered in Maine and Andrew kept a studio in the Olsons’ house, where he painted the farm, the house, and its inhabitants countless times. He said that he was looking out the window of that studio when he saw Christina crawling up the hill after visiting her parent’s gravesite. Christina, however, was not the model for the painting. At 55, she was no longer in her first flush of youth, so Wyeth used his wife Betsy as his model. It lends a bit of implausible pulchritude to an otherwise bleak painting.

“The challenge to me,” Wyeth said, “was to do justice to her extraordinary conquest of a life which most people would consider hopeless.” Personally, I’ve always thought Christina’s World is a fine mid-century abstraction that had reality superimposed on it. If it has an emotional pull at all, I don’t feel it.

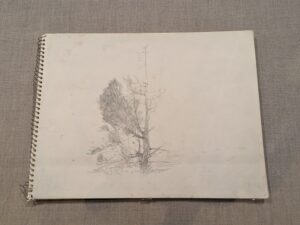

That’s not to dismiss his incredible contributions to art. I encourage my students to spend time looking at his paintings. I stress this because, as I told my flock today, “Before you can paint like Wyeth, you need to learn to draw like Wyeth.” He was meticulous in his preparation.

Yesterday, while looking at watercolors of the interior of the Olson house, one of my students said, “Andrew Wyeth got rich painting the Olsons and their house and farm. Why didn’t he do anything to make their lives easier?”

The Olsons lived in grinding rural poverty. Wyeth’s paintings show unfinished plank walls, or walls with open lath where the plaster has fallen away, or the interior of their barn, untouched by modern agricultural conveniences. They used an outhouse, an unimaginable hardship for a disabled woman.

When MoMA bought Christina’s World, Wyeth became, essentially, an overnight success. There is an unbridgeable gap between that beaten-down farm and the Wyeths’ life in Chadds Ford, PA, so my student isn’t the first person to ask the question. Several sources have written that Wyeth offered the Olson family gifts, but Christina refused any money. How much of that is mythmaking and how much is true, I can’t say. Nor can anyone else, since all the principals are dead.

Even if it is true, there are lots of reasons needy people don’t accept help, including the fear of stigma and loss of pride. Christina Olson could think of herself as Andrew Wyeth’s equal as long as she didn’t accept his money.

There’s no getting around the fact that Wyeth profited from the struggles of a disabled person. Nor did his wealth, built in part on their backs, bring them any relief. The final insult of poverty is that it kills you young. Alvaro lived to 73, Christina to 74. In contrast, Andrew Wyeth lived to 91, Betsy to 98.

That was then, and this is now, and we’re less ethically hazy, right? Every time I see a cell-phone video of a person being assaulted or dragged screaming to an unknown fate, I recognize that there was a cameraman or woman dispassionately filming, not lifting a finger to help the victim. Apparently, cameras without consciences will always be with us.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.