October 3-5, 2008 — North side of Pier 40, Manhattan

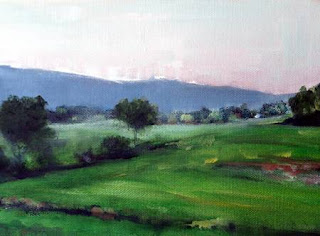

Migrating Geese, by Carol Douglas, 12X9, oil, is among works by thirty New York artists.

Migrating Geese, by Carol Douglas, 12X9, oil, is among works by thirty New York artists.New York, NY – The Lilac Preservation Project (LPP) is pleased to present The Water Works Exhibition, featuring the works of thirty artists from metropolitan New York and the Hudson Valley. The show is curated by Lilac’s artist-in-residence, Amy DiGi. All works are for sale.

Artists featured in the exhibition include: Liz Adams, Yasue Arai, John Baber, Amy DiGi, Carol Douglas, Victoria Estok, Mary Ann Glass, Marilyn Harari, Linda Hubbard, Rick Michalek, Maddy Morales, Sharon Nakazato, Rein Singfield, Christopher Staples, Ruth Ternovitz, Joe Vacara, Diane Waller, Marcia Wiley, Elizabeth Winchester, Kristin Zimmermann and others

The

Lilac, built in 1933, is an historic, decommissioned US Coast Guard vessel that served as a lighthouse and buoy tender in New Jersey. She is the last surviving vessel in her class. (For details about her history and the mission and work of the LPP, see

here.)

The Water Works Exhibition is open to the public Friday through Sunday, October 3-5, from 10 AM to 6 PM. The public is invited to a reception on Saturday, Oct. 4 from 6 to 9 PM. All Lilac exhibitions are open to the public free of charge.

Subway: Take the #1 train To Christopher Street. Walk west along Christopher Street to West Street (West Side Highway), cross to the Pier and walk south 2 blocks to Pier 40. Or take the #1 train to Houston Street and walk west along Houston Street directly to the Pier.

Bus: Take the 8, 10 or 21 bus lines. PATH directions: To Christopher Street Station. Walk west along Christopher Street to West Street (West Side Highway), cross to the Pier and walk south 2 blocks to Pier 40.

Car: Pier 40 is located 2 blocks south of Christopher Street off of West Street (West Side Highway).

.jpg)