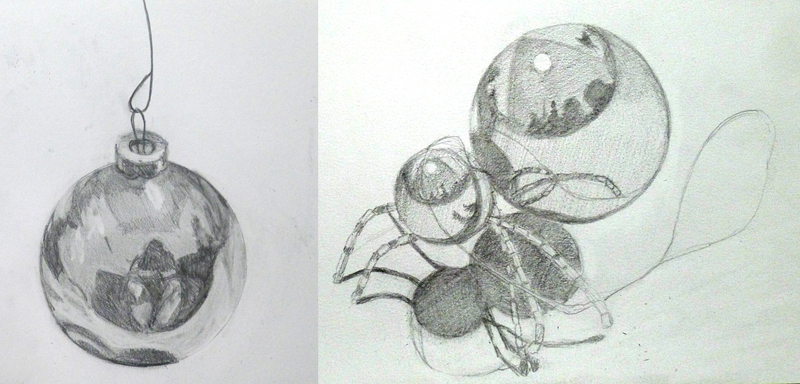

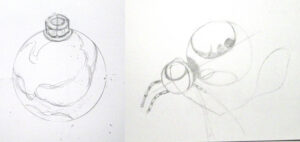

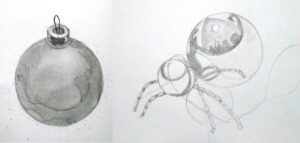

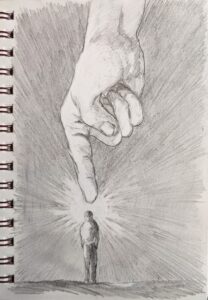

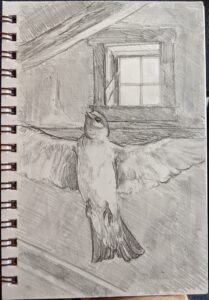

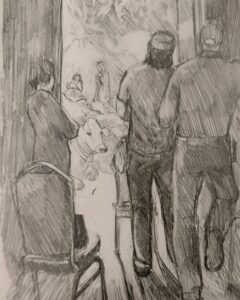

Susan Lewis Baines is an artist, gallerist, and the wrangler of a gorgeous and goofy half-grown puppy-in short, an all-around good egg. I had an idea for a Christmas exercise, but when I saw what Sue made, I asked if I could share it instead. It’s far more exciting.

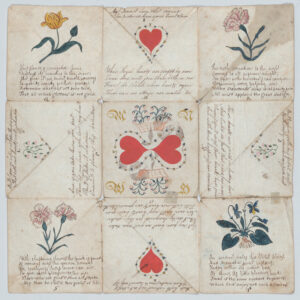

Sue’s project is called a puzzle purse, and it is a craft with a long and storied pedigree. Tato (flat paper envelopes or boxes) date from Japan’s Heian era (782-1185 AD). They were used as portable storage for small items like buttons, pins and needles, or stamps.

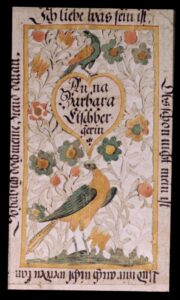

How they got to Europe, I don’t know, but by the early 18th century, puzzle purses were being used to exchange romantic messages in both England and America. Meanwhile, immigrants brought a distinctive calligraphy from Germany called fraktur. They applied this to puzzle purses to create highly complex love letters (liebesbrief) and envelopes.

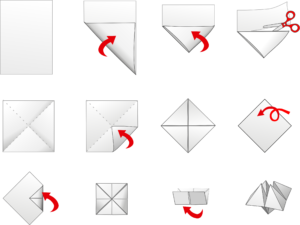

Because I’ve never made a puzzle purse, I’m sending you to the Origami Resource Center for detailed instructions.

A variation

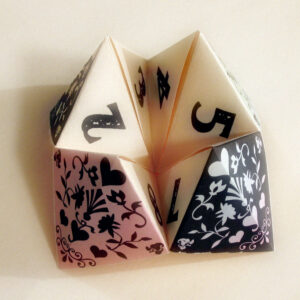

If you were a kid within the last century, you’re familiar with a paper fortune teller, or ‘cootie catcher,’ as it’s called in some parts of the US. This simple piece of folded paper also has deep roots; while it was first described in an 1876 German book for children, it resembles much older fortune-telling frameworks. Although it looks like Japanese origami, it’s European in origin.

In my childhood, adults had no part in making cootie catchers. Today you can find instructions for them all over the internet. Predictably, these adult-suggested fortunes are dull, like “signs point to yes,” or “doubtful.” I remember them as being far goofier, like “You’ve got cooties!”

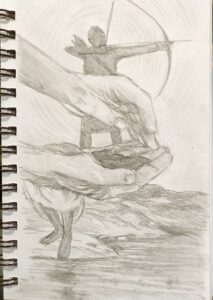

Why not marry Sue’s idea for a holiday puzzle purse with the cootie catcher? Just replace the colors, numbers and fortunes with similar little illustrations to Sue’s. For anyone who ever used one, it would be a charming surprise, a twist on a happy childhood memory.

What you need

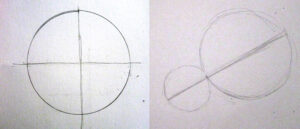

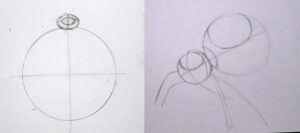

Sue did her puzzle purse in colored pencil, but you could also use watercolor. Use any foldable, reasonably lightweight hot-press paper (cold press will be more difficult to fold). If you have a bamboo or bone folding tool, it would be a nice refinement, but it’s not necessary.

Enclose an ornament hook and your puzzle purse or cootie catcher will become a treasured ornament.

Aren’t you glad I didn’t go with Plan A, which was to have you draw the packages under your Christmas tree? Now, get to work. I can’t wait to see what you come up with!

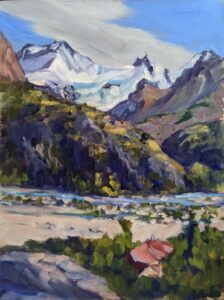

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

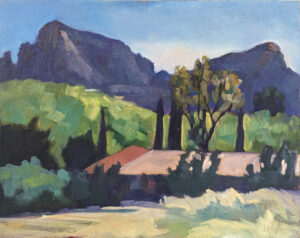

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.