If like me, you are a lifelong resident of the northeast, you may have only a dim or cartoonish idea of the culture and landscape of Texas. Before last year, my only experience there was a drive-by of the statehouse in Austin and several days poking around San Antonio and the Hill Country. There are moments in those places that are unbelievably beautiful, but I’ll be the first person to admit my knowledge of Texas is only skin deep.

“You need to come visit and teach here,” my friend and student Mark Gale told me repeatedly. Yeah, yeah, I told him. A workshop needs more than just spectacular scenery; it needs students. And yet Mark and I somehow pulled it together and we had a fantastic group.

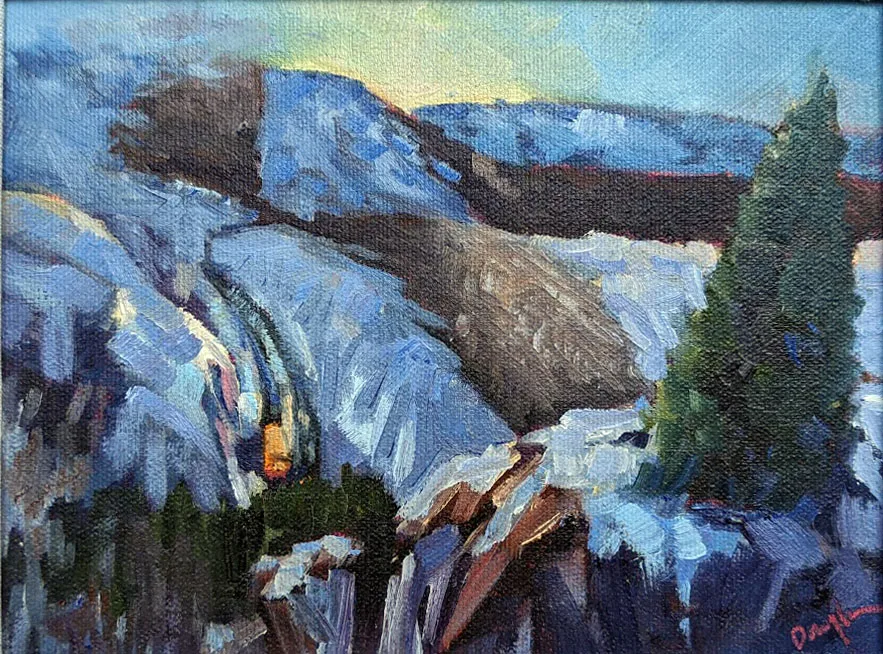

But that’s not what I wanted to tell you about. Rather, I’m here to sing the praises of McKinney Falls State Park. When Mark mentioned it to me, I was skeptical. After all, it is just a few miles from downtown Austin. I wasn’t prepared for the solitude and peace of the place, or the beauty of knotted cypress roots. Onion Creek spills over a massive, long limestone scarf, and the water is a delicate blue-green-grey. Above all, there were lupines in their thousands.

Still, from a visitor’s standpoint that’s never enough. We need bathrooms, and the toilet block was fresh and clean. Where were the outhouses I’d expected there in cowboy country? (To be honest, we have state parks here in Maine where an outhouse would be a luxury.)

We residents of the northeast have the idea that with our four hundred years of history we are somehow more civilized than newer, rawer states. Mention Texas in New York and your odds of an anti-Texas comment are about 50-50. That’s absurd. Texas is so large and varied that it defies description. It’s also historic. The first European settlement in Texas was only 61 years after the Pilgrims founded Plymouth colony.

Texas parks are beautiful and wildly diverse. That’s not just in terms of terrain, but in wildlife. We were painting lupines along McKinney Falls’ ring road, when I noticed skeins of birds high in the sky. “Canada geese?” I asked tentatively, because that didn’t make sense to me. No, they were pelicans. Meanwhile Mark has sent me photos of buffalo from Caprock Canyon, which could give the red rocks of Sedona a run for their money. There are armadillos, wild boars and rattlesnakes.

If I’d had time, I could have hiked, camped, or fished. In the more remote parks, there are extraordinary stargazing opportunities. Because of light pollution, most of us never have a chance to see the heavens unfolded but there are still empty places in Texas.

The other thing I loved about McKinney Falls State Park were the children. There were hundreds of them on school field trips, learning about and loving nature.

Yesterday the wind chill was below zero as I hiked up Beech Hill. I like Maine’s weather, but I spent the walk musing on lupines, which is why I decided to share this blast of spring with you. The lupines will be out in just a little more than two months, and I’ll be there teaching. I hope you will join me.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.