When Mary and I were kicking around Newfoundland in 2016, Kyle from St. John’s insisted to us that there weren’t bears in Newfoundland. “But there are bear-proof trashcans all over!” Mary replied. Later, a toothless old woman from Hare Bay with an impenetrable accent told us that yes, indeed, there are bears in Newfoundland. Wikipedia confirms this.

This woman was born in Hare Bay and had never left. In the waning light, we watched a mink swim toward shore as cars converged on the spare frame churches. She told us the whole village goes to church on Sunday evening. That’s how isolated Newfoundland is, both physically and culturally.

Atlantic Canada has a long history of European settlement. Portuguese and French fishermen were probably fishing the Grand Banks in the 15th century and around 1520 the Portuguese established a colony. Newfoundland was Britain’s first overseas colony, claimed in 1583 under Elizabeth I. Quebec is so old that it was settled under the semi-feudal Seignorial System (which you can still see in the lot lines on the Île d’Orléans). And then there’s the only verified Viking settlement in the New World, L’Anse aux Meadows, settled around 1014 AD.

We were on our way to L’Anse aux Meadows when we stopped to visit the wreckage of the SS Ethie. Hurricane Matthew was blowing up the coast, shifting from rain to blizzard. It was a day much like the day when Ethie broke up in the tumultuous seas off Gros Morne.

Ethie was a coal-burning steamer on the Bonne Bay–Battle Harbour run, carrying herring, cod and passengers. People have speculated that its captain, Edward English, was either anxious to get his passengers home for Christmas or under pressure from the home office. At any rate, on December 10, 1919, she set out on the leg from Cow Head to Rocky Harbour, carrying 92 passengers. That’s a short run of less than 50 km, but the weather glass was falling fast.

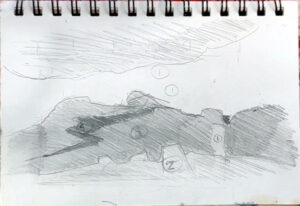

Within a few hours, it was blizzarding. The west wind pushed Ethie towards land, and she burned most of her fuel staying off the rocks. Captain English realized he had no choice but to beach at Martin’s Point. Ethie was spotted by Reuben Decker, who rushed to help with his dog Wisher. Newfoundland dogs are famous for their stoic temperament, muscular build, thick coat and webbed paws, all of which make them great cold-water swimmers.

Wisher swam from shore to fetch the rope that would be used to make a breeches buoy. That’s a rescue device that’s something like a zip line with a float attached.

All 92 passengers and the crew were rescued, including an 18-month-old baby.

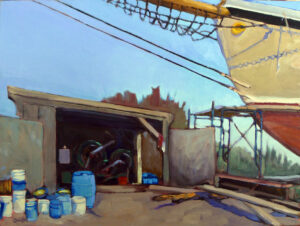

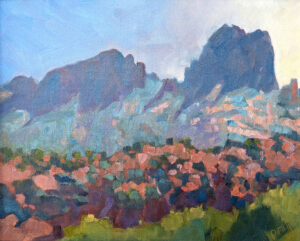

The wreckage of Ethie can still be seen today, scattered over thousands of feet of shoreline. Mine is a fantastical interpretation of the shipwreck, as I’ve compressed elements. I seldom get stuck into the details like this, but here the abstraction is in the objects themselves; it couldn’t have been painted in my usual loose style. Besides, it’s good to occasionally remind people that I can paint with precision when I want to. As Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “Consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”

Last Friday, I released Step 5, the Foundation Layer, of my Seven Protocols for Successful Painters. This is the heart of painting, where the first layer of color is applied, and I promise, you’ll learn lots.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.