“Have you written about original art sales being final?” a reader asked me this weekend. “Do you ever accept returns? If so, why or why not?”

My late friend Gwendolyn used to regularly shop on what she called ‘The American Plan.” Gwendolyn wasn’t an abuser of the system; she didn’t wear clothes and then try to return them. Instead, she’d bring things home from the mall in a variety of sizes and colors, hoping her family would like something she’d selected. The rest would go back.

American retailing encourages this, with most sellers offering very liberal return policies. That makes sense for large corporations in the highly-competitive world of online consumer goods. It makes less sense for custom goods made by small workshops, like jewelers, painters, or seamstresses.

Before you start selling paintings, you should think through your return policy, or you may be asked to do something you’re not willing to accommodate.

Since I have a commerce-enabled website, Google requires that I have a clearly-articulated return policy for both my paintings and my workshops, which you can read here. Without it, Google won’t rank my website, which means nobody would ever see it.

You determine what your policy is, but I think “no returns at any time, for any reason,” would be unreasonable. Art does occasionally arrive with damaged frames. Even though I always ship with insurance, it’s good customer relations to manage the repair or reimbursement myself.

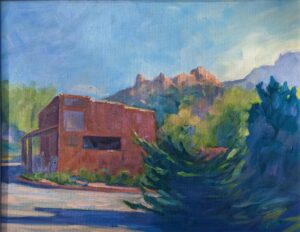

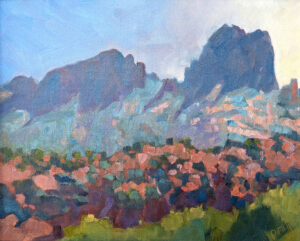

It’s devilishly difficult to photograph paintings. There’s inevitably some difference in color. A person with a very tight color scheme might realize the blue of my ocean doesn’t quite match their couch. I used to worry about this a lot, until I bought some wall paint online during COVID. My husband’s office is beautiful, but it’s not what I saw on my monitor. Nobody can manage color perfectly online because every screen shows color differently. (Then there’s airbrushing and photo enhancement. Although it doesn’t pertain to my paintings, most product photography is enhanced before we ever see it.)

Having said that, I work hard to make accurate photos and I’ve never had a painting returned because it didn’t look like the photo.

The buyer has more responsibility for paintings bought in my gallery or at an event. He or she has thumped the tires and understands the work’s physical presence. There is no reason for the same return policy in a bricks-and-mortar store but whatever it is, it should be posted.

I and many other gallerists will send a painting ‘on spec’ if asked. That means the customer pays for it up front (as a surety). If they decide they don’t want it, they pay for its return and insurance. The time limit for this must be clearly specified in advance. Two weeks is more than sufficient to realize a painting just doesn’t work.

No matter what your return policy is, your long-term goal should be to keep your client. Start by asking why they want or need to return the item. Once you determine that, you can offer them a more appropriate product for purchase or exchange. For example, in the example I gave above, I’d show them my entire inventory of ocean paintings. (If they didn’t die of boredom, they’d be bound to find something that’s a better match.) Sometimes people simply can’t visualize size, and buy something that’s too small. If that’s the case, offer them a credit toward a larger one, and don’t be afraid to offer them layaway if the price scares them. A painting is a lifetime investment, and we want to do everything possible to help people able to afford art.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.