I’m off to an opening at the Red Barn Gallery in Port Clyde this afternoon (4-7 PM) If you want to join me, drive to the foot of Port Clyde Road, turn right on Cold Storage Road and it’s on your right.

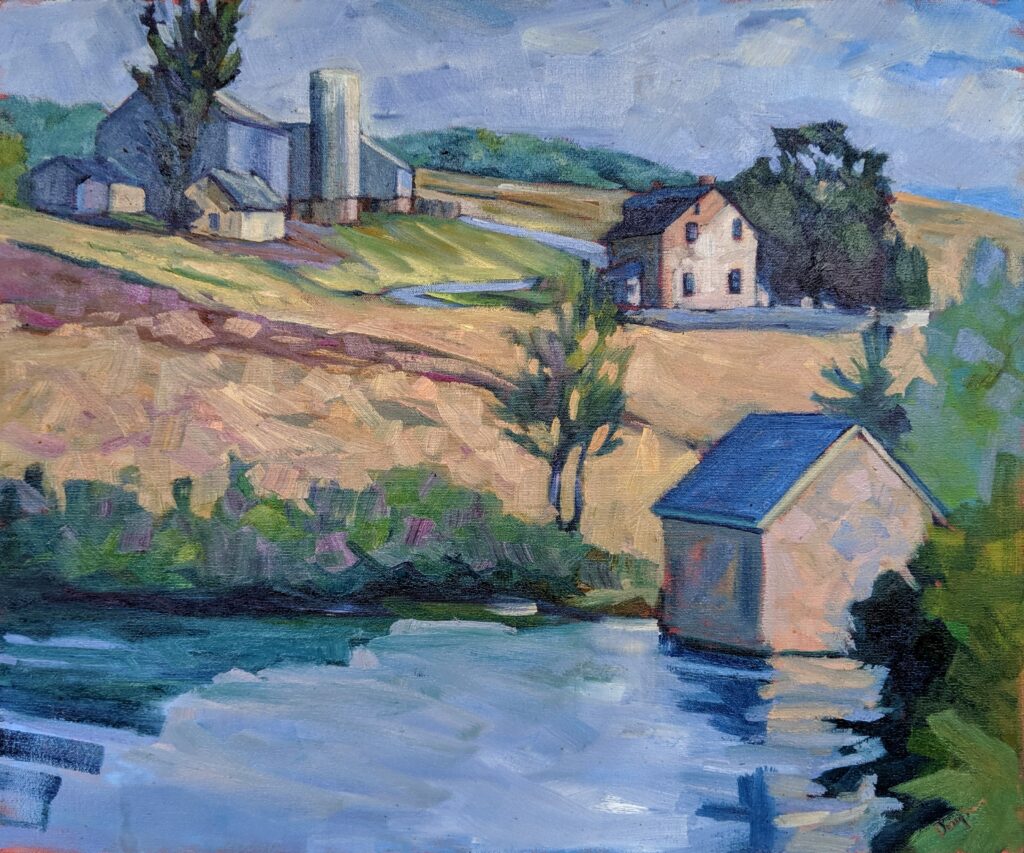

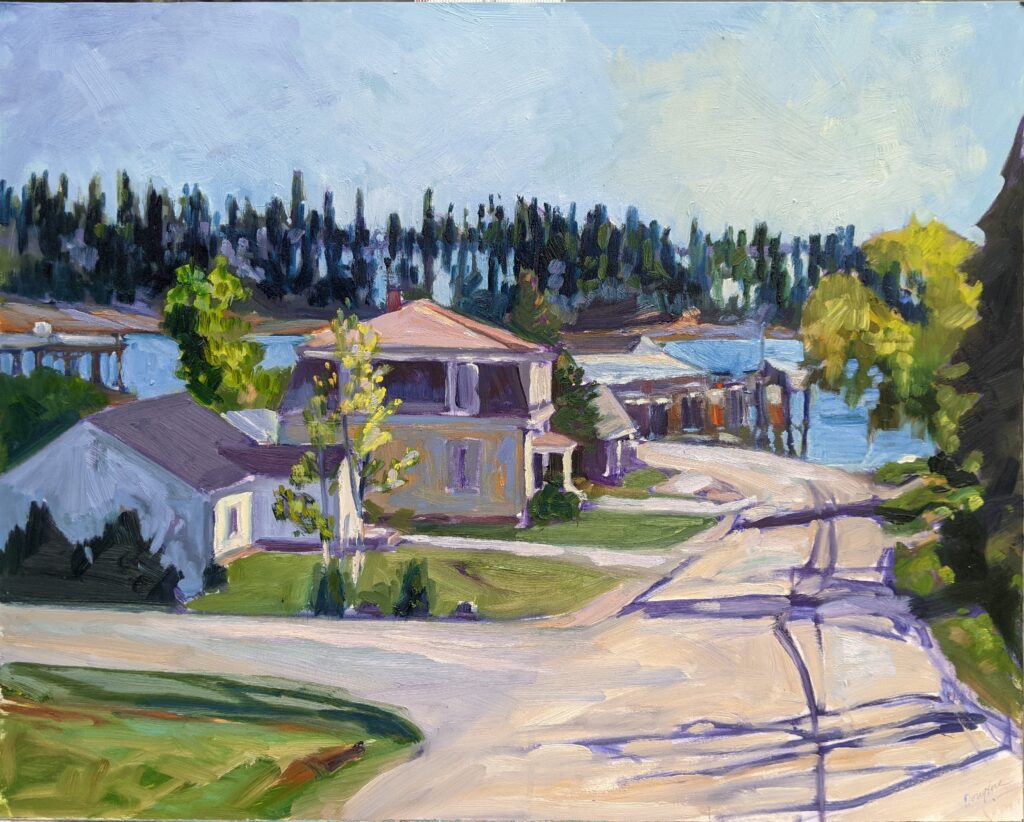

This show focuses on barns, and three of my paintings are in it: a springy equipment shed in Warren, a bright red barn in New Brunswick, and the above Home Farm at Winterthur.

Having just returned from Britain, I’ve contemplated the 18th and 19th century estates that the du Pont family were copying when they dreamed up Winterthur. Winterthur started as a small Greek Revival mansion, expanded until it contained 175 rooms and more than 2600 acres of land, and is now a public museum. That’s the same trajectory as followed by many British Great Houses, except that their transit took hundreds of years, not a mere century.

Henry Francis du Pont was a shy, awkward man. After studying horticulture at Harvard (really), he came home to manage Winterthur. Although he was an autocrat in many ways, it’s to Henry Algernon du Pont’s credit that he didn’t force his only son into the shark-infested waters of early-20th-century business.

The younger du Pont styled himself a farmer, and became one of America’s premier breeders of Holstein Friesian dairy cows. But with 250 field employees, he didn’t have much in common with the typical American farmer of the early 20th century. That fellow and his family were doing grinding chores, often in terrible weather, and always one jump ahead of crop failure. In contrast, Du Pont was a gentleman farmer, insulated from disaster by his family’s wealth.

Winterthur’s estate was assembled by buying up a few dozen local farms. By 1925, the estate was raising turkeys, sheep, chickens, hogs, cows, vegetables and flowers. Winterthur also had greenhouses, a sawmill, a railroad station, and a post office. There were the show-stopping gardens and the du Ponts’ premier collection of Early American interiors.

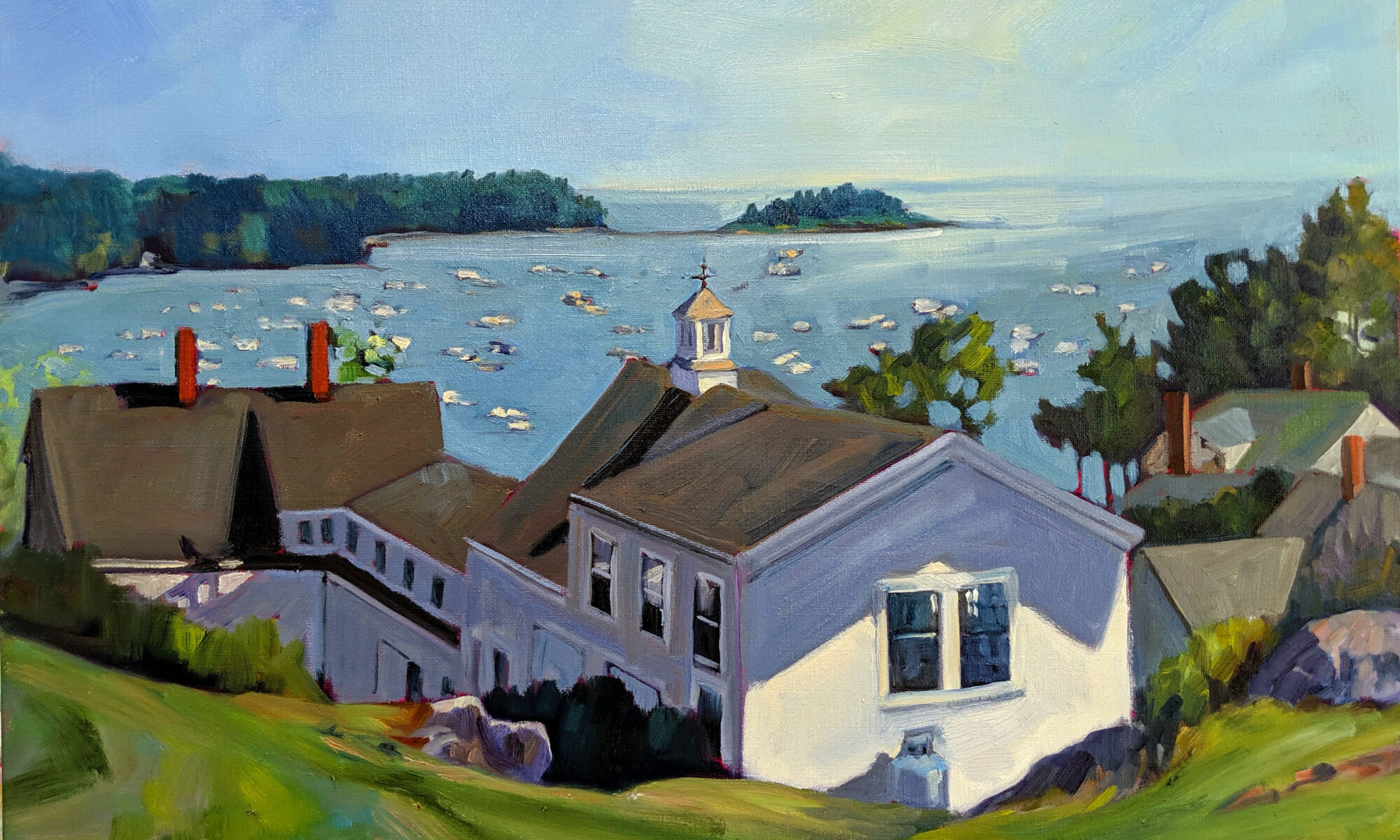

The lovely stone house I painted above was the home of one of the farm managers. It is not the fanciest of the 90 outbuildings on the estate, but it’s my favorite. I imagine it is far pleasanter inside than the manor house, which is now our premier museum of American furniture and decorative arts. These artifacts, sometimes including whole rooms, were bought up and salvaged when nobody much cared about Early American design. That, rather than farming, was Henry Francis du Pont’s great contribution to our culture.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.