When Colin Page asked me if I’d paint for the 76th annual Camden Garden Tour, I said, “sure, why not?” Don’t ever tell him I said this, but Colin is such a nice guy that he makes one want to do nice things too.

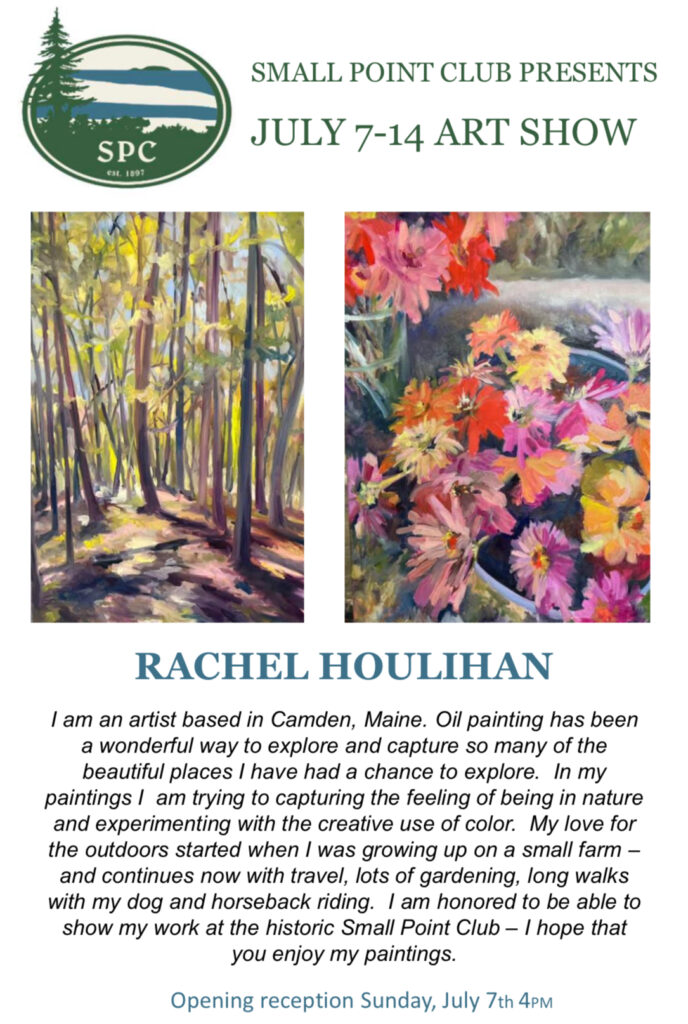

I’m not a painter of gardens. They’re one of the few landscape subjects I avoid. The painter can’t generally improve on what the skilled gardener hath wrought. Great gardens (as Merryspring Nature Center’s are) are beautiful, but they’re also neat. My natural inclination in landscape paintings is toward the scruffy, like me.

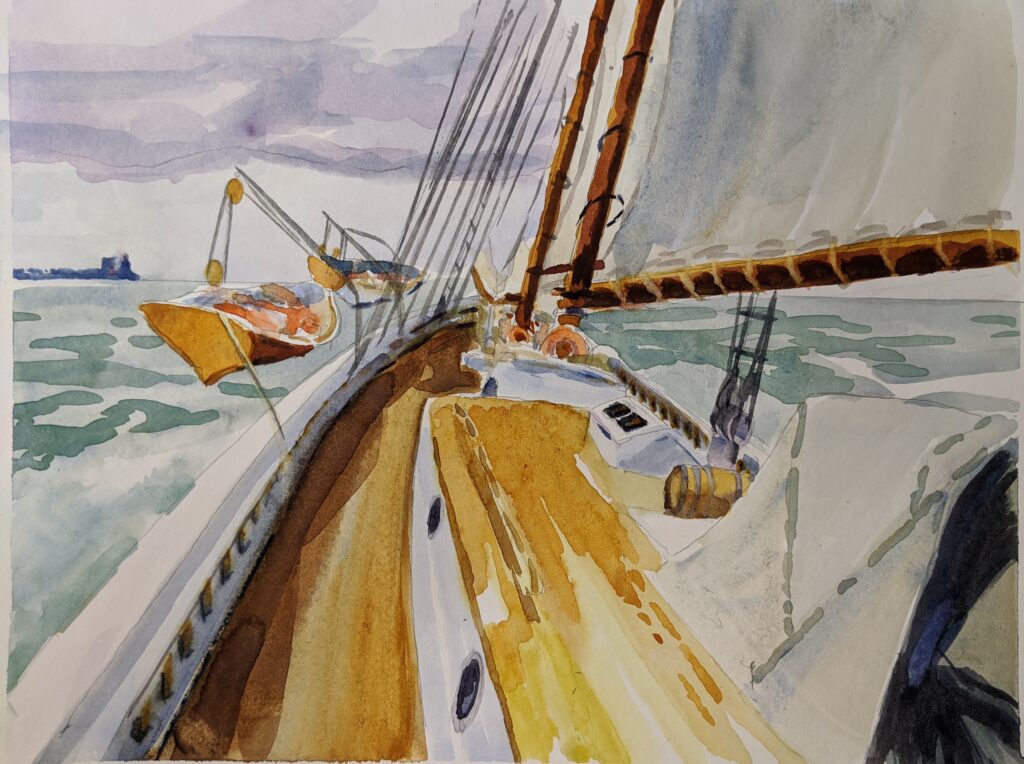

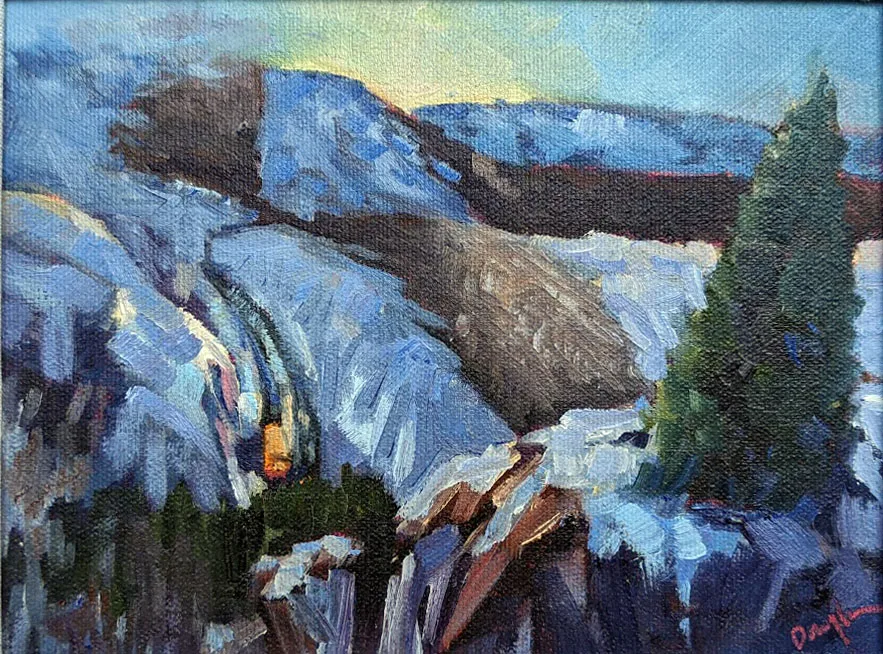

The contrast between the intense color in the foreground and the airy lightness of the great daylily bed at Merryspring appealed to me, even as I realized it would be a compositional bear and equally difficult to paint.

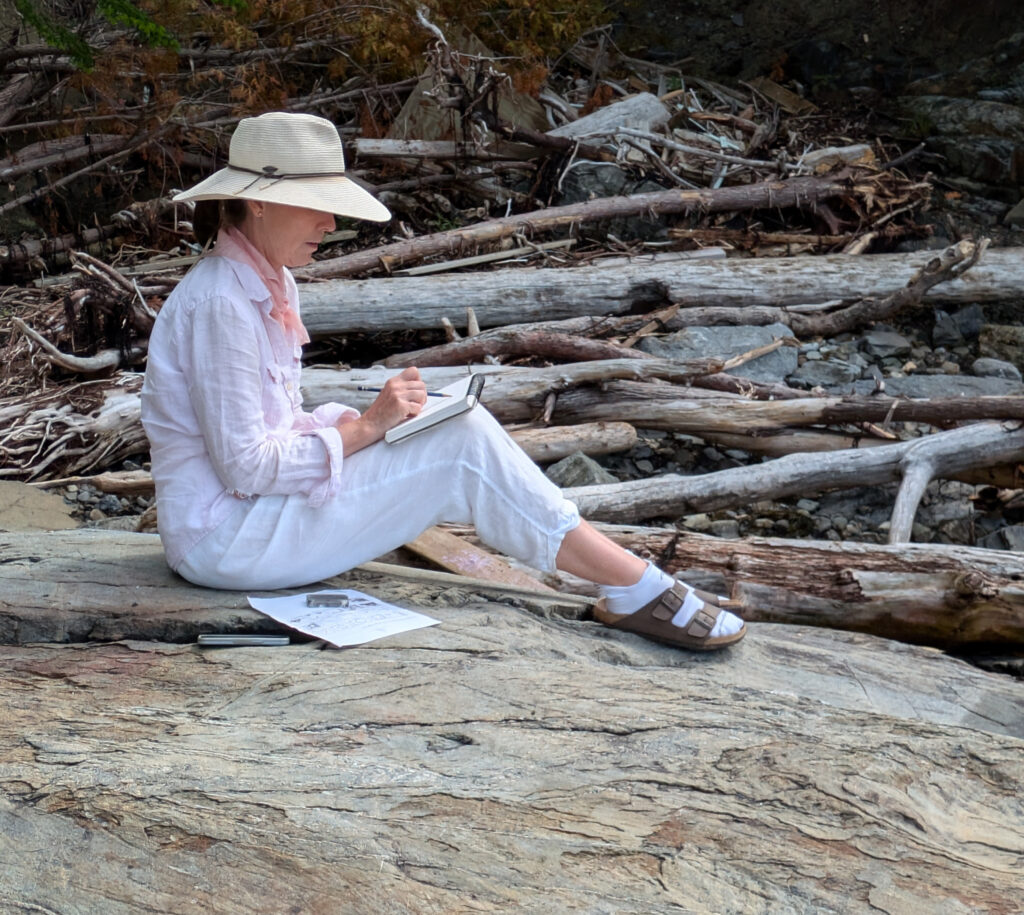

“Never proceed to paint until you have a drawing you love,” I tell my students. My problem was, I kept jabbering with passers-by. It’s a small town and I’m blessed with many wonderful friends. I didn’t finish my sketch until noon. Since I had to leave at 3 PM to get ready for the Camden Art Walk, it was time to fish or cut bait.

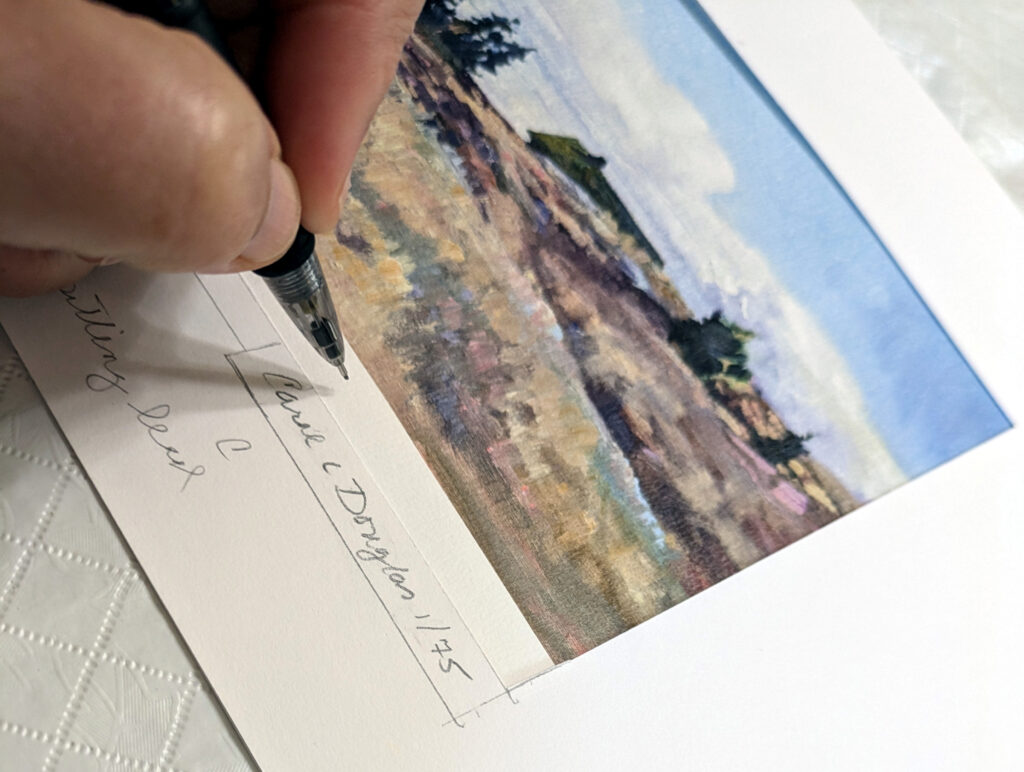

The featured artist for this year’s Garden Tour is Cassie Sano, who has studied landscape painting with me on and off for several years now. My students are passing me left and right in their Cadillacs.

This canvas is certainly not overworked, since I finished it at warp speed. It was a good warm up for Camden on Canvas, which starts this morning.

As we do every year, Björn Runquist, Ken DeWaard, Eric Jacobsen and I started a last-minute text string debating where we should paint. Dithering is an important part of the plein air landscape painting process; after all, there might be something brilliant right around the corner.

But here in Camden there’s not a single intersection or overlook that wouldn’t make the bones of a good painting. I know what I’m doing, and I suspect the Three Musketeers do too. The good lord willing and the creek don’t rise, I’m rowing out to Curtis Island on Friday and painting on Sea Street on Saturday. But double-check at the information kiosk on Atlantic Avenue just to make sure.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.