As I write my next class, Applied Color Theory, I am building a framework of the most important aspects of color and light for the painter. Color theory is a comprehensive framework that starts with the color wheel and works out from there. If you know your way through the following concepts, you don’t need more color theory. If you’re fuzzy about them, perhaps it’s time for more study.

Hue, Chroma and Value These are the three properties of color.

Color Harmonies This is the idea that certain color combinations are more pleasing to the eye and can evoke specific moods or responses.

Color Context This includes how colors affect each other when placed side by side and the psychological effects of color.

Color Systems and Models We all learned subtractive color (the classic color wheel) in school, but additive color behaves differently. Knowing how light combines will give you a better grasp on color temperature.

Color and Culture Colors have cultural overtones; for example, we believe red is ‘hot’, blue is ‘cool’ and closely-analogous colors ‘clash’. How important are these ideas to painting, and how much of our color sense is just fashion?

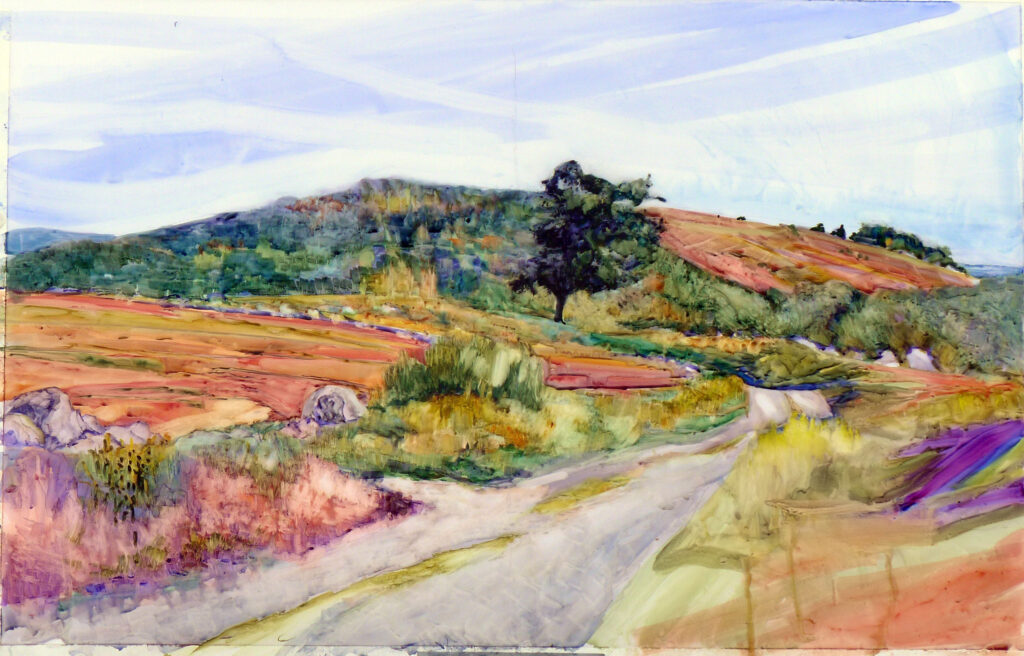

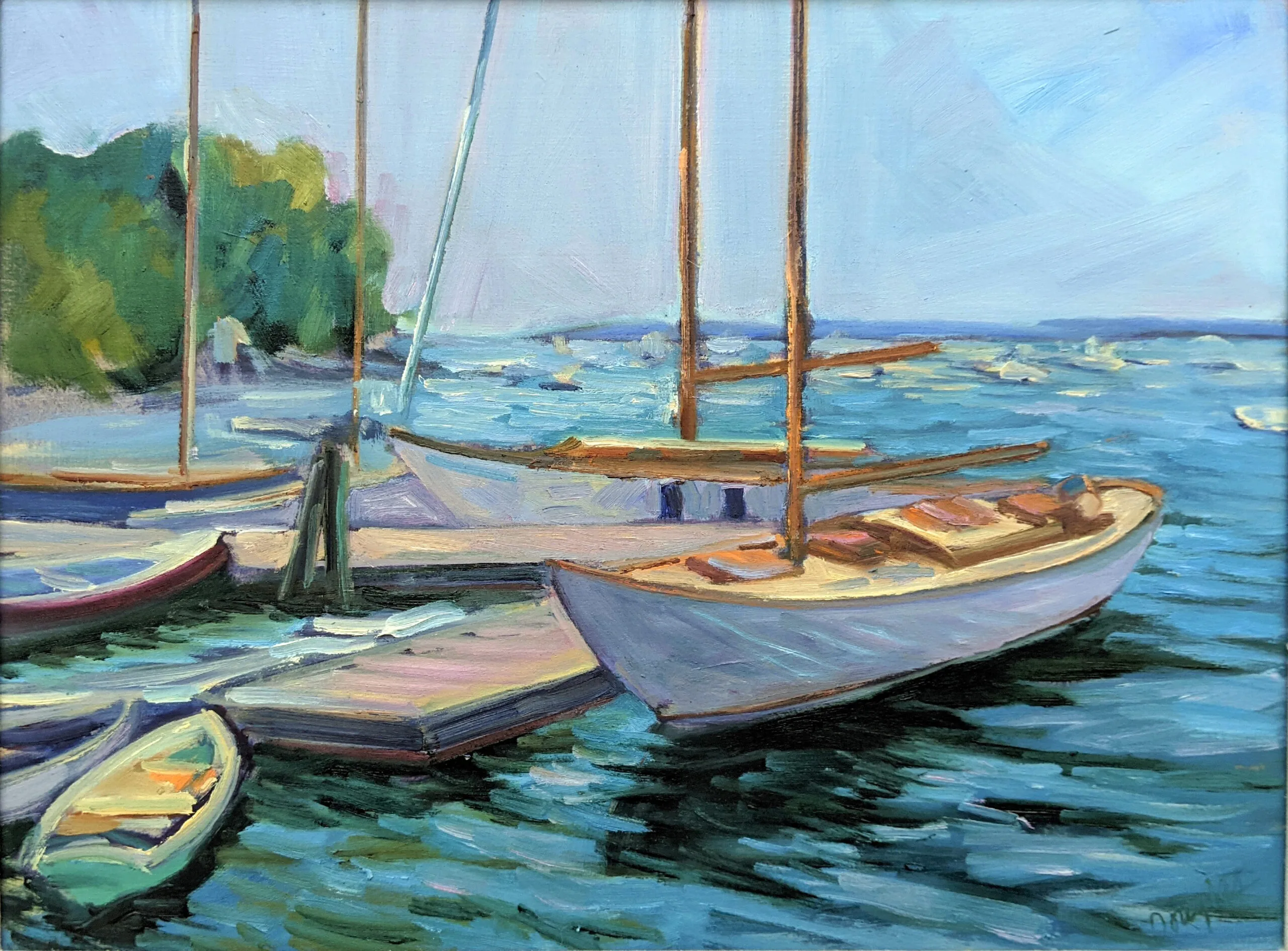

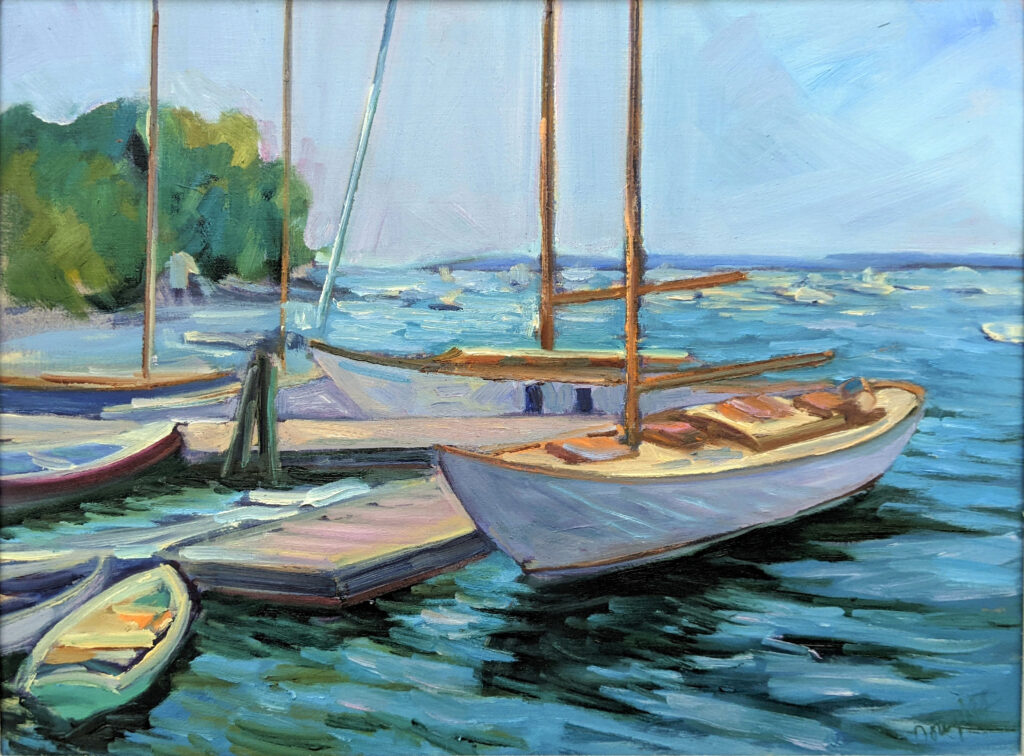

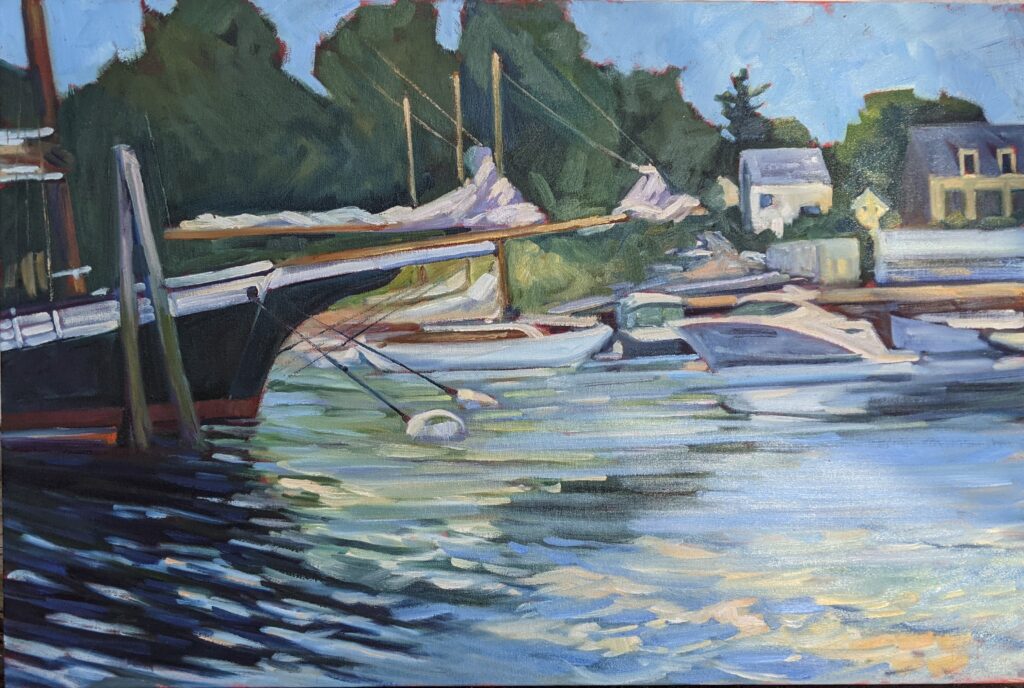

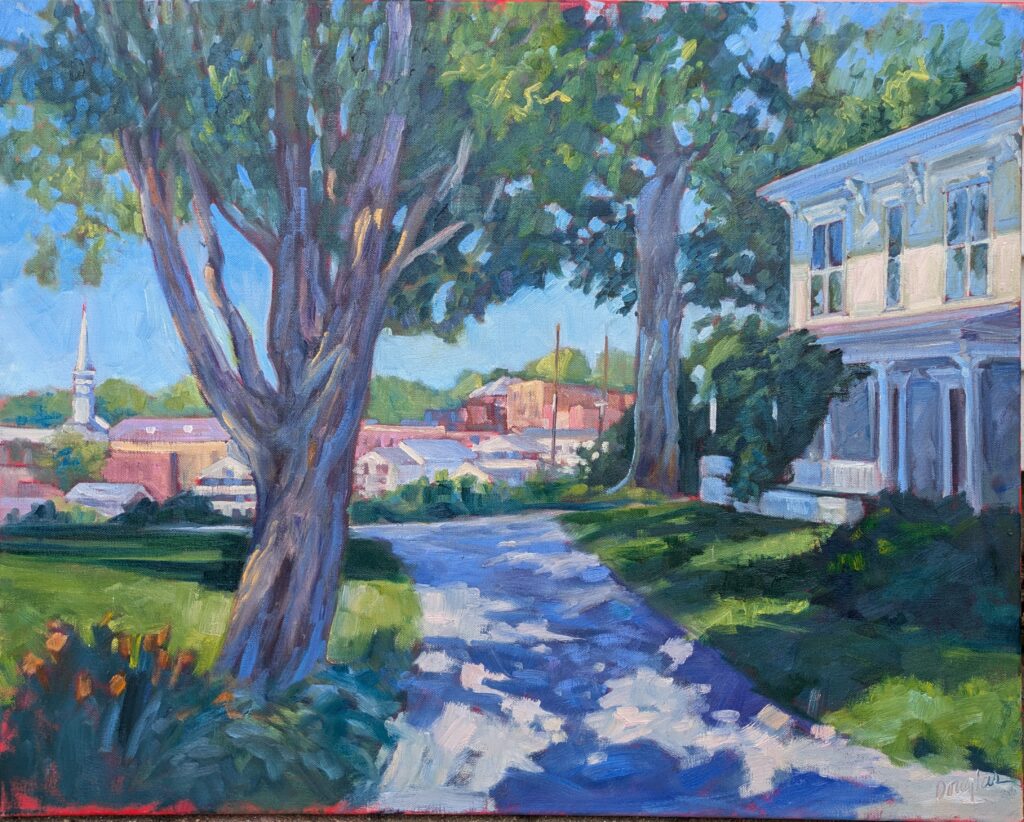

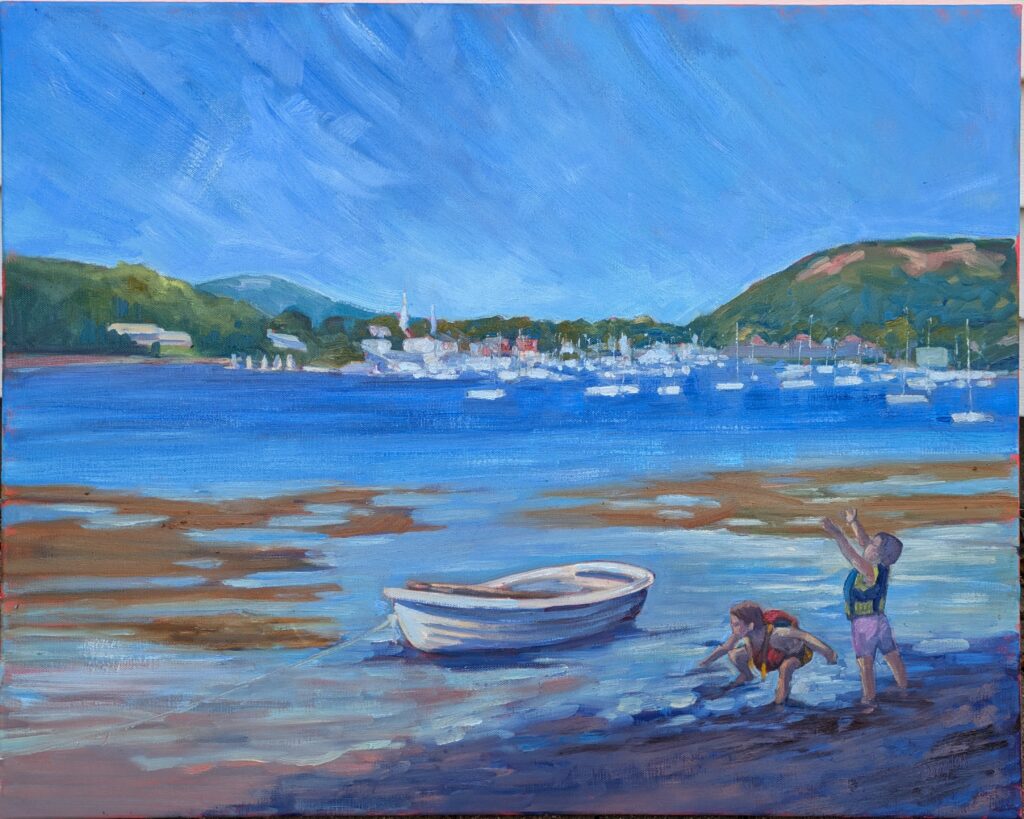

Color temperature All light has a color. All shadow has color. How do we figure them out?

Light direction and intensity Light and shadow are fundamental compositional elements. That includes whether light is soft and diffuse or hard and direct. Closely related is:

Reflectivity Whether an object is matte or shiny affects how it plays in the color sphere.

Transparency and Translucency The ability of a surface to transmit light affects how light is depicted. Transparent objects (like glass) and translucent objects (like frosted glass or thin fabric) have different light interactions from opaque objects.

Atmospheric Perspective Light behaves in predictable ways the farther you are from the object. Can you articulate the order in which color falls off?

Mood Light can significantly influence the mood and emotional impact of a painting. Bright, intense light can create a sense of drama or tension, while soft, diffused light can evoke calmness and serenity.

Time of Day and Season The color and quality of natural light change throughout the day and across different seasons, affecting how scenes are depicted.

Can I do all that in six weeks?

I’ll do my best. This painting class is open to all mediums and skill levels.

It will run for 6 weeks on Tuesdays, 6-9PM EST. Participants will be sent a zoom link.

Dates:

August 20, 27

Sept 3, 10, 24

October 1

I’m prewriting this before I hit the road to teach at the Schoodic Institute and in the Berkshires. I don’t know how many seats are available for this class by the time you read this. Check here; you won’t be able to register if it’s full.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.