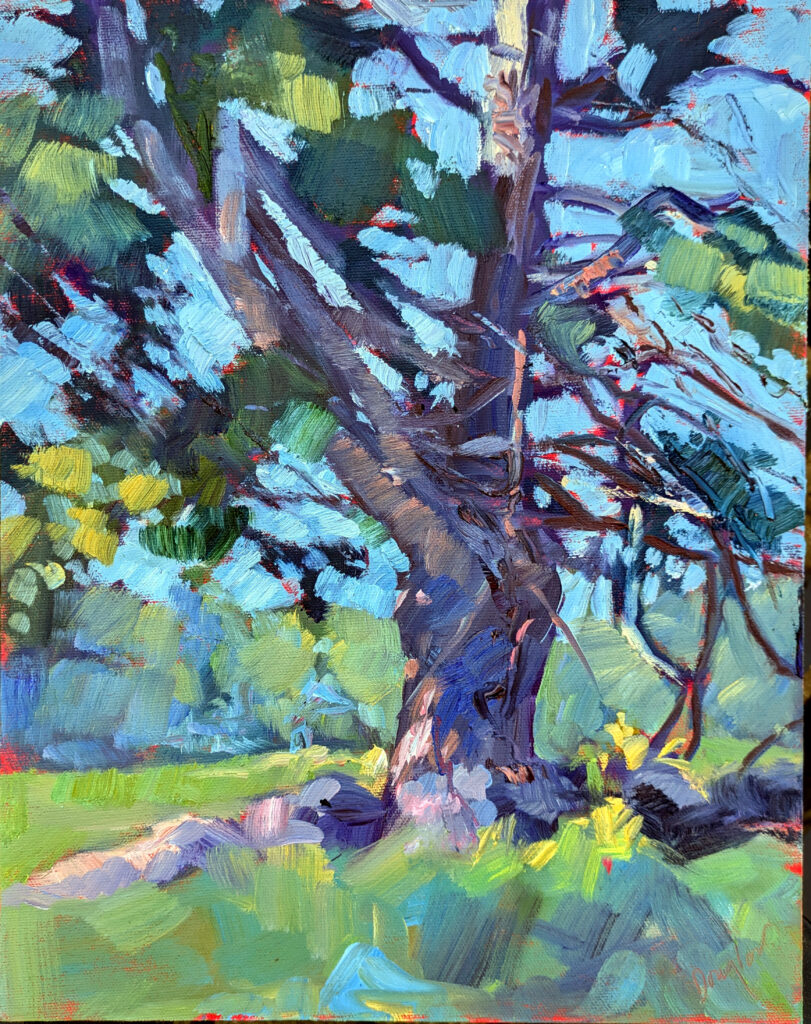

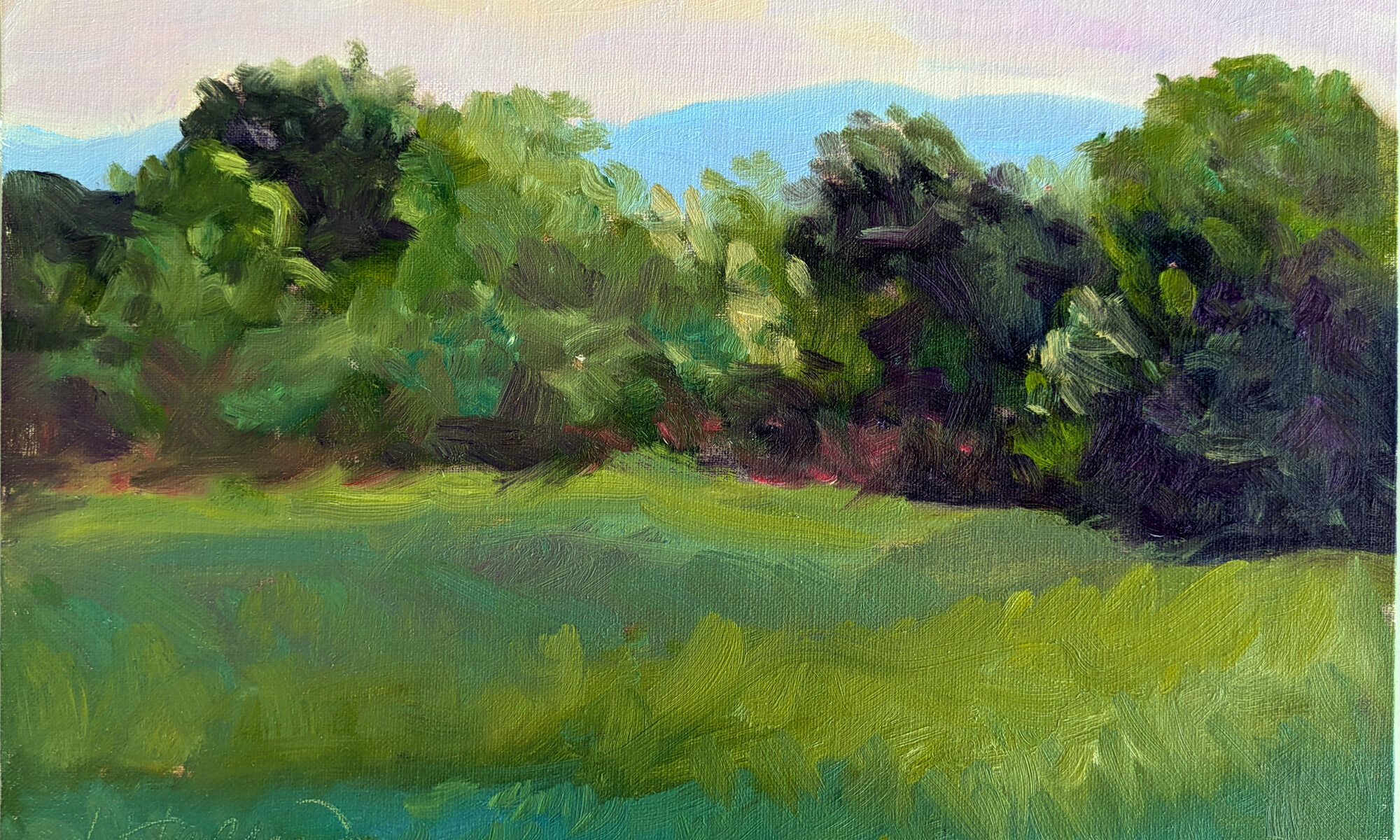

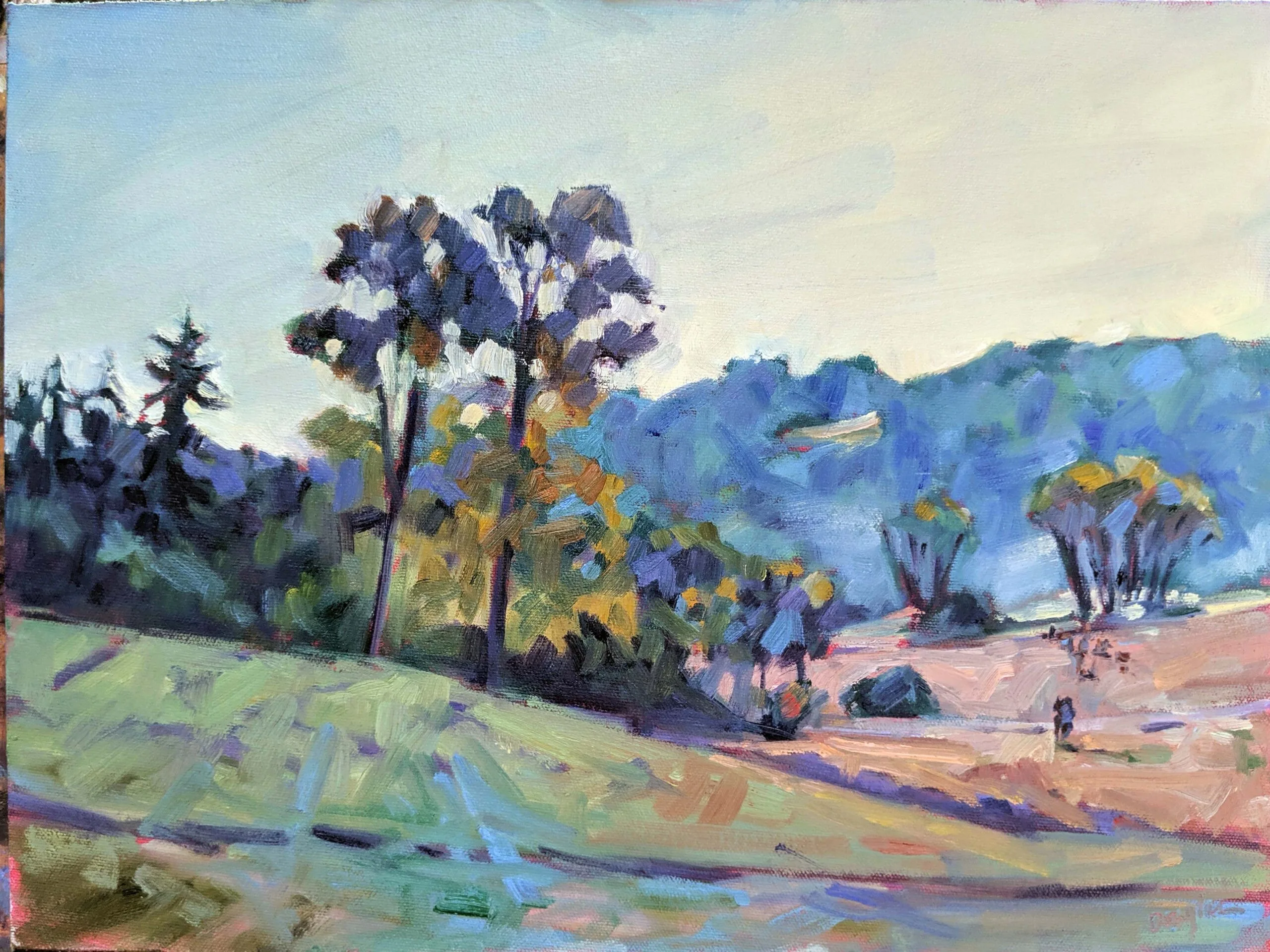

There is a young maple tree that I watch from my living room. This morning, it’s green overlaid with bronze. The maple behind it has a golden hue where it’s hit by the sun, but the part in shadow is a very dull blue. Closer to my house, the neighbor’s tree is developing dull violet overtones.

We old-timers say that maple trees start turning color before the kids go back to school. That’s not strictly true, because maple trees change their color throughout the season, starting with the brilliant red buds that we recognize as one of the first signs of springs. New leaves are chartreuse and mature into the full-throated, deep, dull “wall of green” that’s the undoing of many painters. There summer sits for a few hot weeks before it begins to slide inexorably into the cooler air and warmer tones of fall. By autumn’s end, all the deciduous leaves will be gone except those of the young beeches and oaks, which will dry yellow and bronze on their stems and create a quiet susurration in the winter woods.

But ask us what color a tree’s leaves are, and we’ll invariably say, “green.” We won’t specify the glossy dark green of summer oak leaves, or the delicate light green of the katsura tree. (I have one in my back yard, and as the leaves dry and fall, they smell like apple pie.)

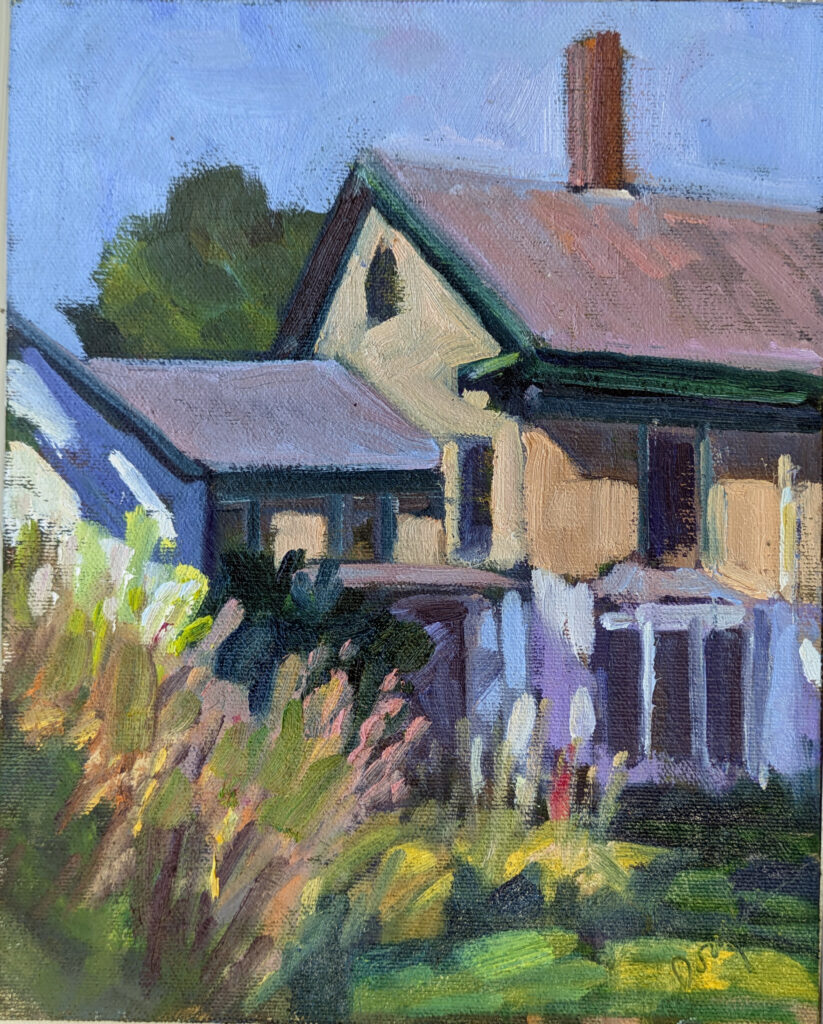

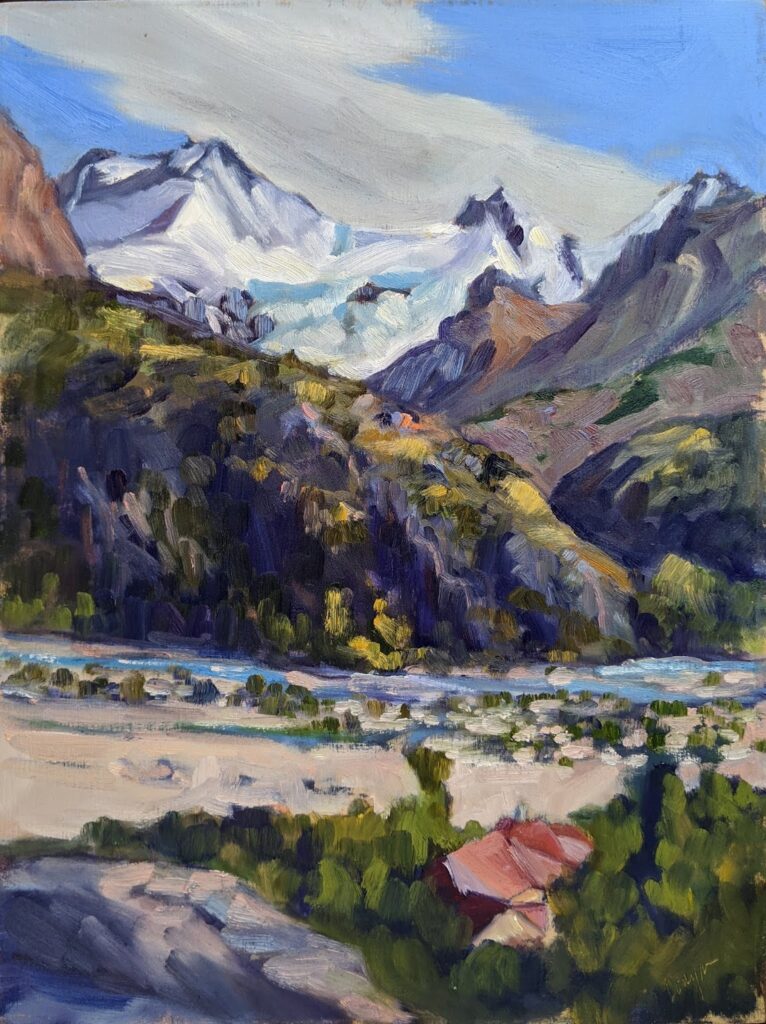

The green that many painters use for foliage bears about the same relationship to the natural world’s green as Gatorade does to juice.

Do you see what I see?

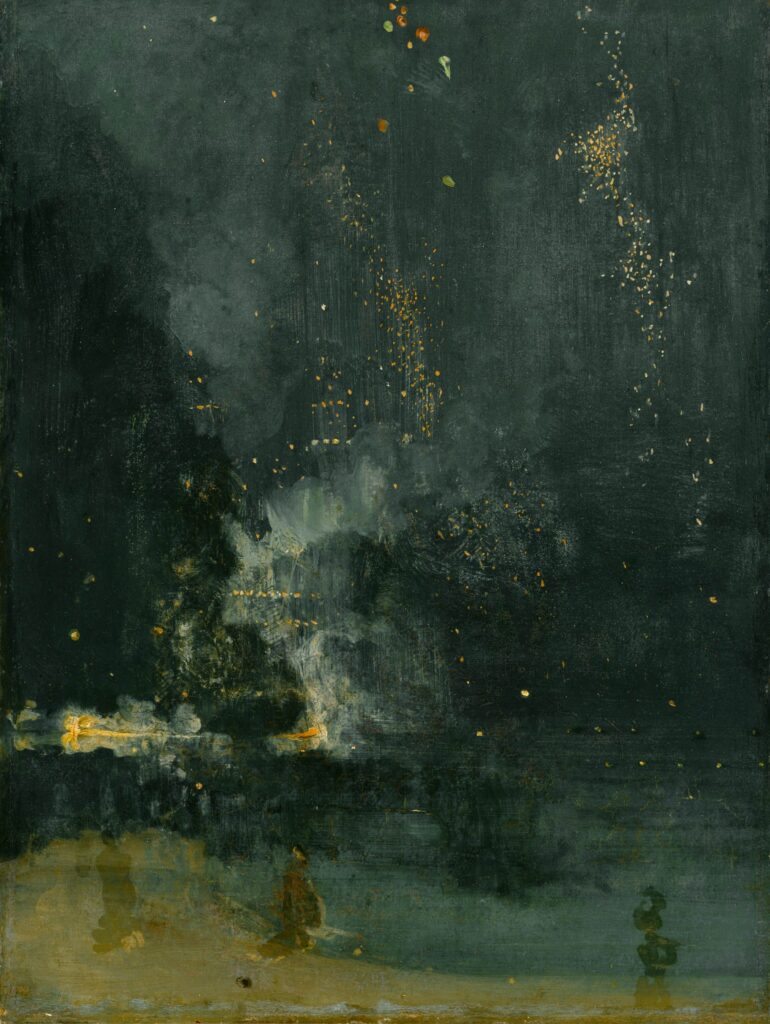

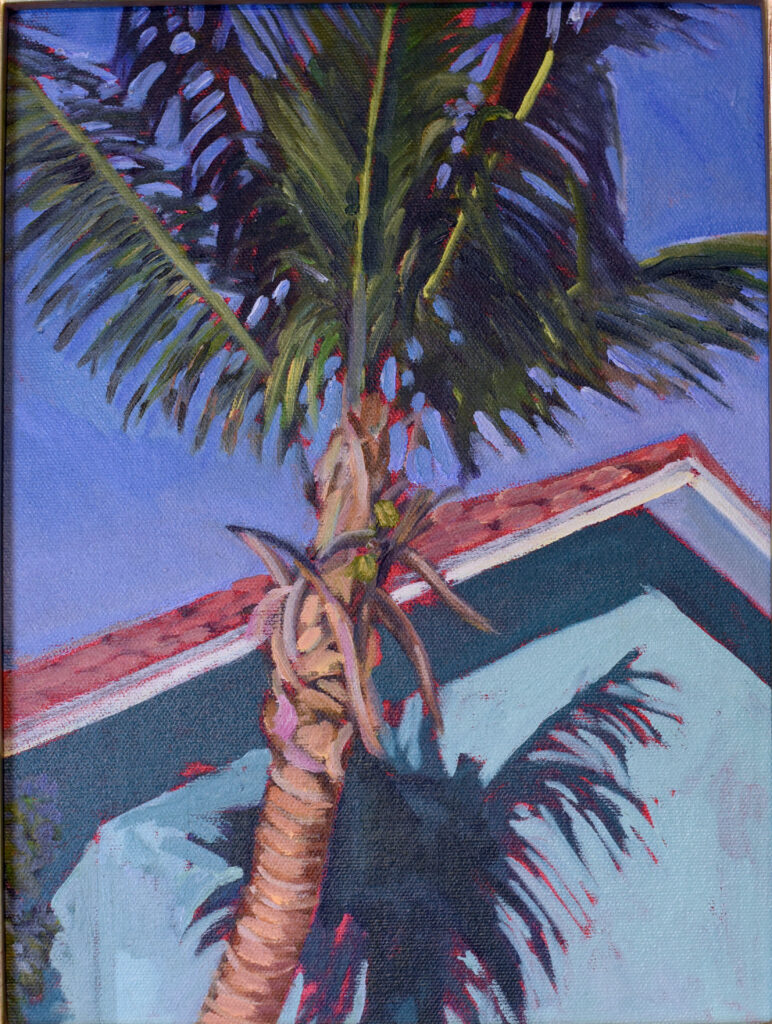

Sometimes I paint with sunglasses on, because I like painting contre jour and the light hurts my eyes. As much as people tell you not to do that, I never notice much problem matching values; my glasses are limiting the light reflecting from my paint and canvas as much as they are the light bouncing off the ocean. (Where they make a difference is in specular highlights, but forewarned is forearmed.)

Visual perception varies from person to person, but within our own brain, we make consistent adjustments. If you always see things as pinker than I do, you’ll see your paints that way, too, and unconsciously make the correction. Not that we really know what anyone else sees; how could we measure that?

Are you looking or thinking?

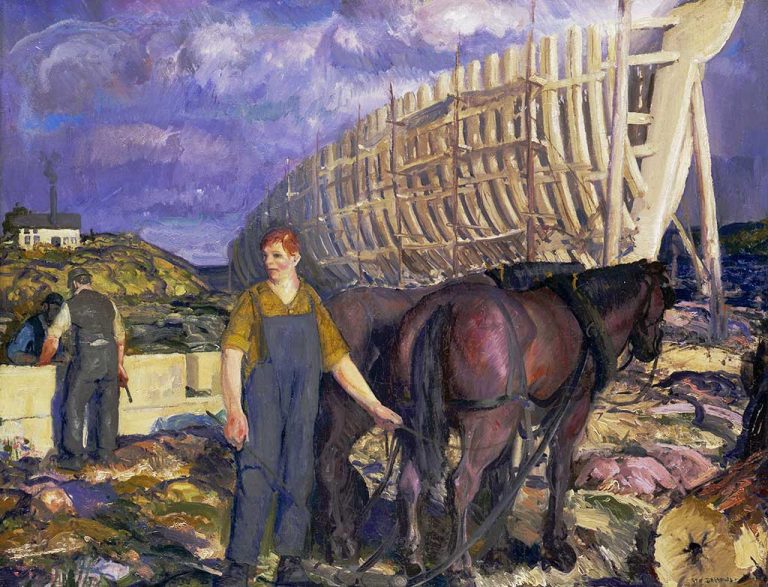

We humans are too smart for painting. We paint with our reason rather than our eyes. For example, we ‘know’ that the irises of the eye are round. We paint that without noticing that for most of us, our top lids cut off a wedge of this pie shape. We know that barns are red, so we don’t notice that the bright red barn on a far hill is in fact objectively brown; our minds interpolate the color for us.

What do you really look like to others?

“Who is this old woman looking at me in the mirror?” my mother once asked me. Most of us carry around a mental snapshot of ourselves that’s a combination of all our prior selves, real or imagined. That can make a candid photo or unexpected compliment tough to take.

That’s, I think, the same phenomenon as described above. Our inner selves know us rather than see us objectively.

What’s the solution?

Time and practice are the great healers for this problem. Meanwhile:

• Consciously look at things as if you were seeing them for the first time.

• Take the time to measure; that forces you to be objective.

• Draw or paint the same subject from different angles.

• Look for subtle color shifts and patterns.

• Observe light and shadow without thinking about what object you’re drawing.

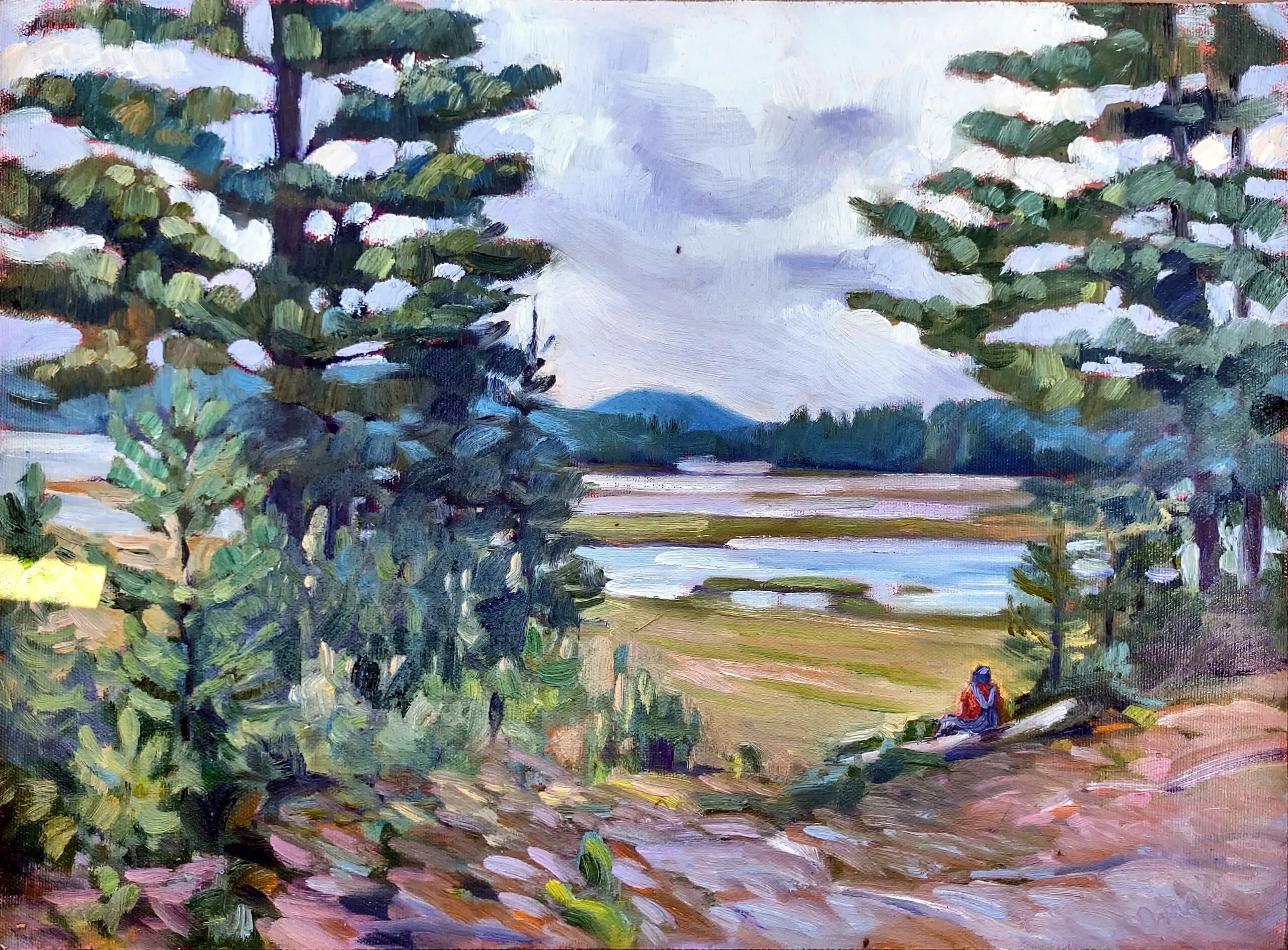

Mark next Friday on your calendar

Grand opening

Carol L. Douglas Gallery at Richards Hill

Friday, September 13, 5-7 PM

394 Commercial Street, Rockport, ME 04856

For more details, see here.

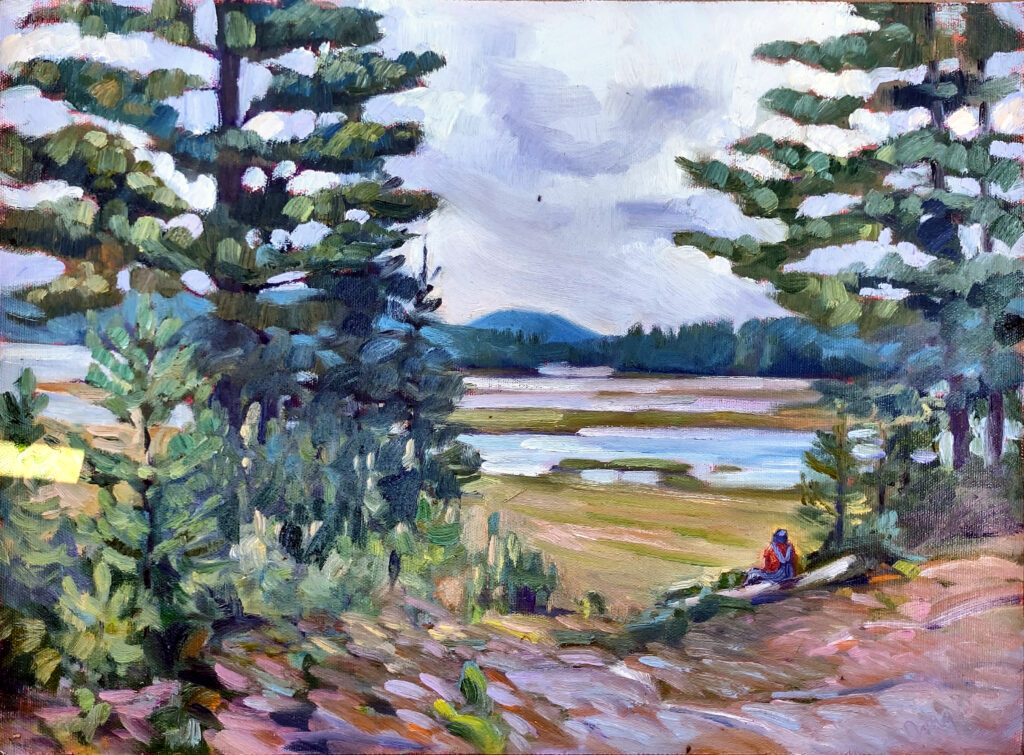

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.