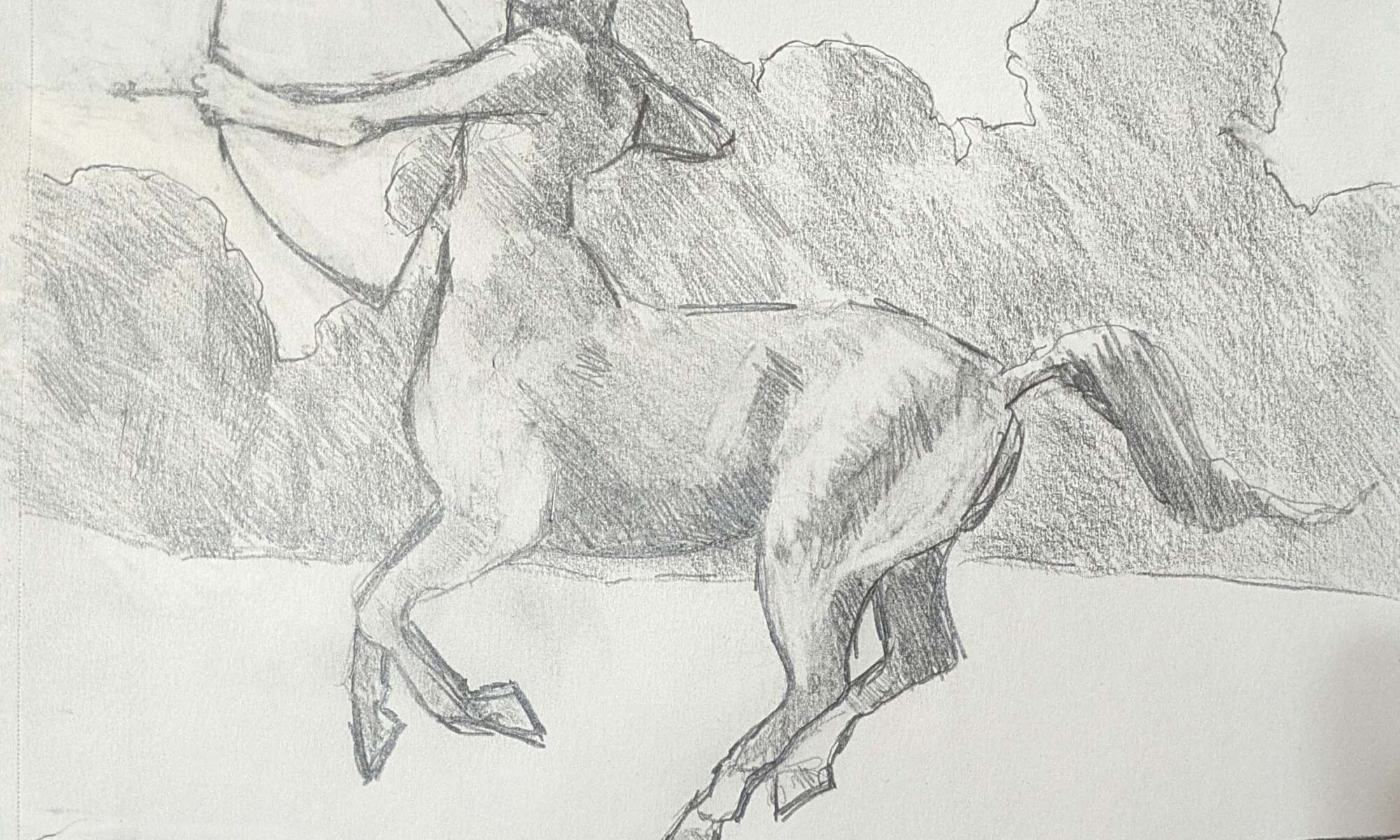

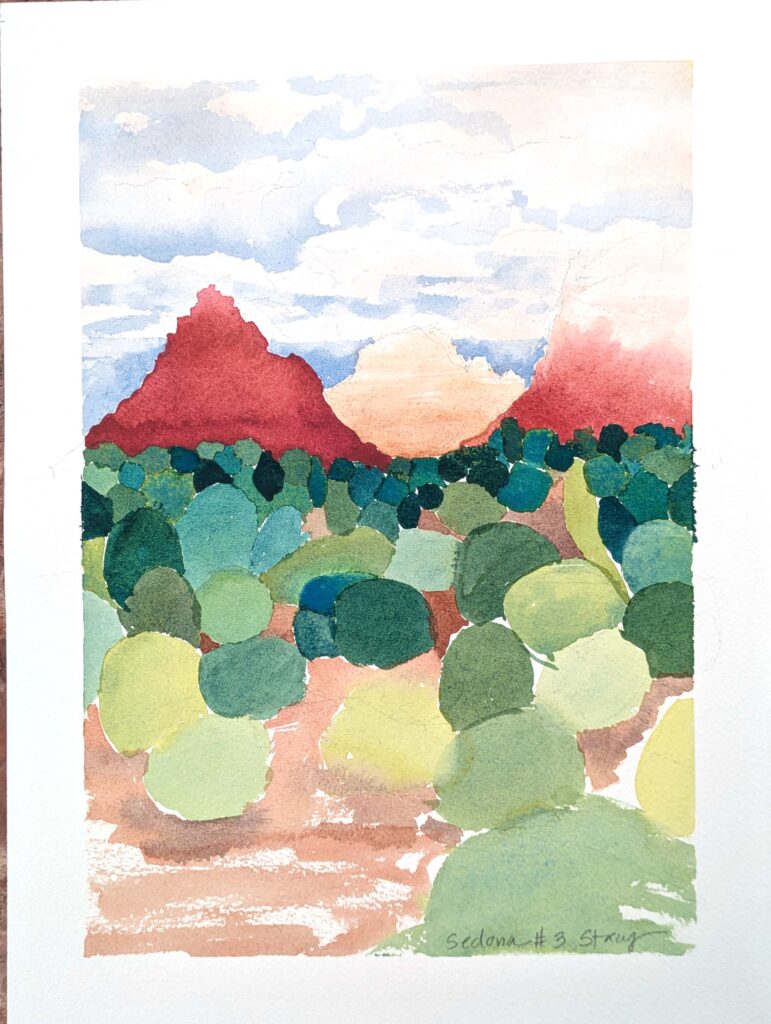

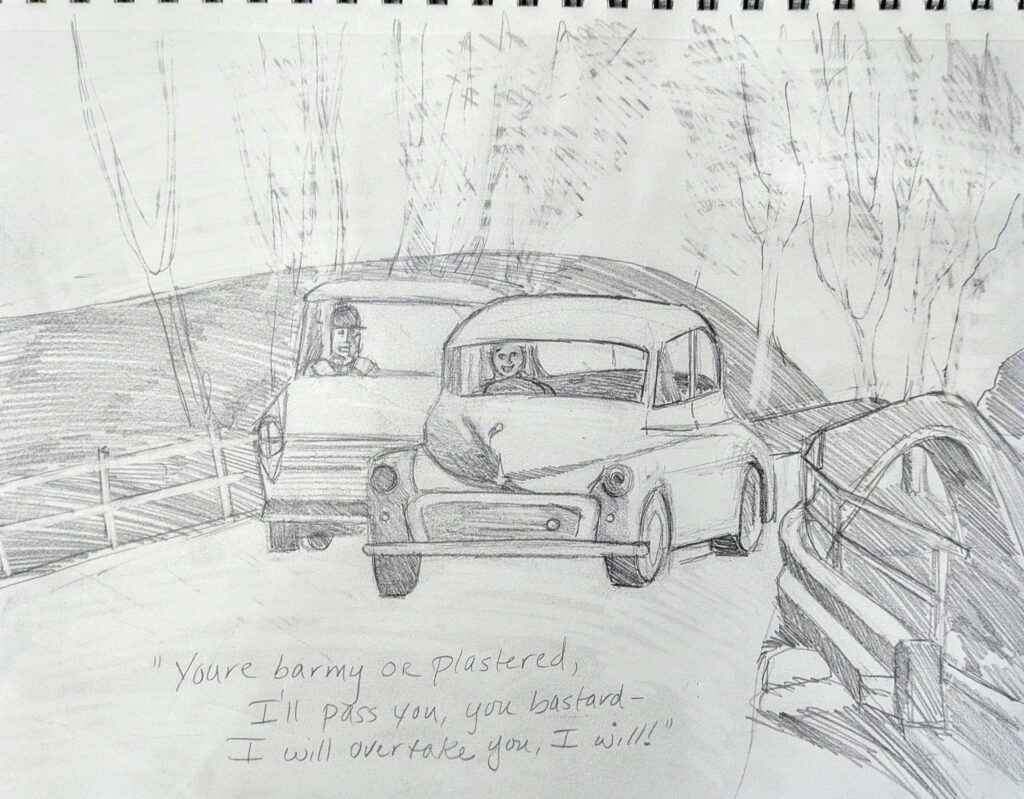

The 1960s and ‘70s were no time to be a traumatized child. Drawing and doodling saved my sanity. So why do some educators persist in limiting doodling in their classrooms?

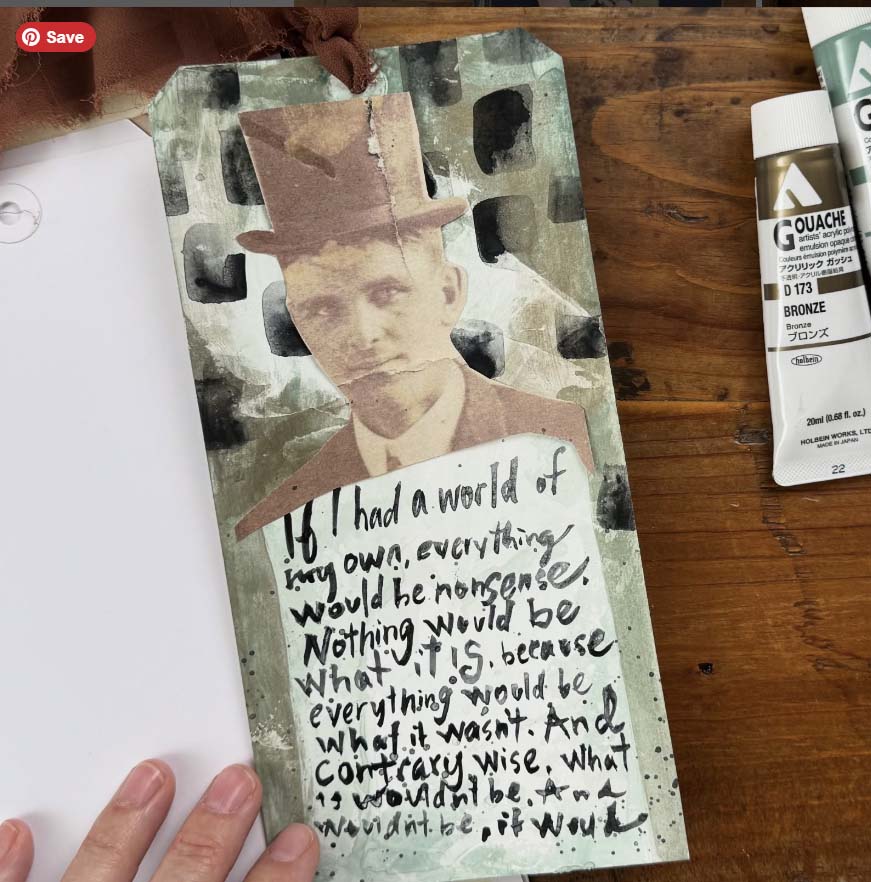

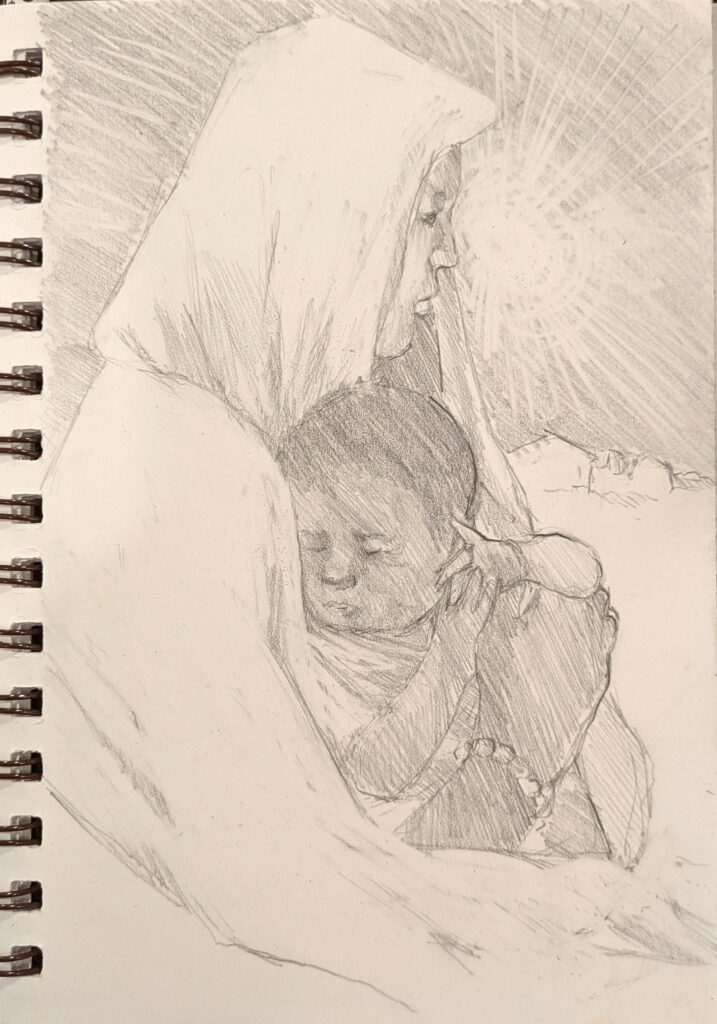

Doodles are found on the margins of ancient manuscripts and cave walls, which means that spontaneous acts of drawing have been with us for far longer than we’ve penned our kids up in school.

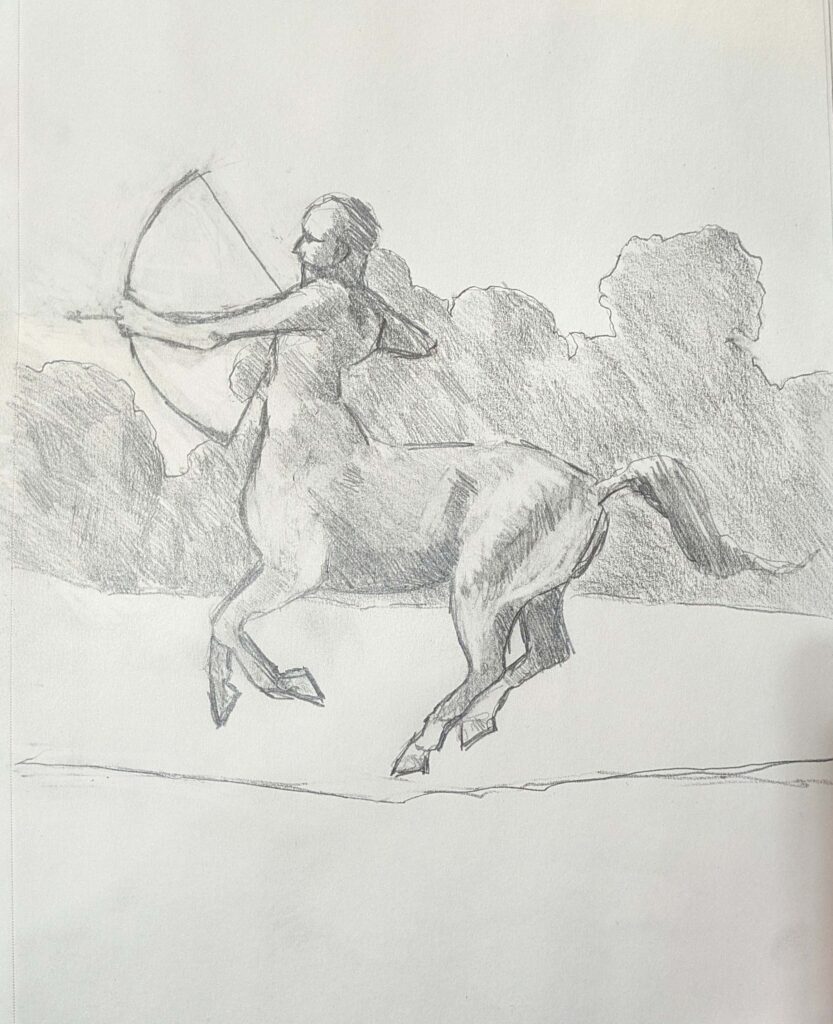

Research shows that doodling helps with memorization and concentration. Our minds are free to wander when our hands are busy. Of course, none of that was known when I was in school; I imagine my teachers just thought I was hopeless.

A 2009 study showed significantly better memory retention among doodlers than among non-doodlers. Perhaps that’s because drawing relieves stress.

I take notes on my laptop, and it’s a terrible habit. Whether we ever look back at them or not, writing notes results in better retention. More words are better than fewer, and writing by hand is better than tapping them out on a mechanical device. For one thing, you can’t draw all over your phone screen.

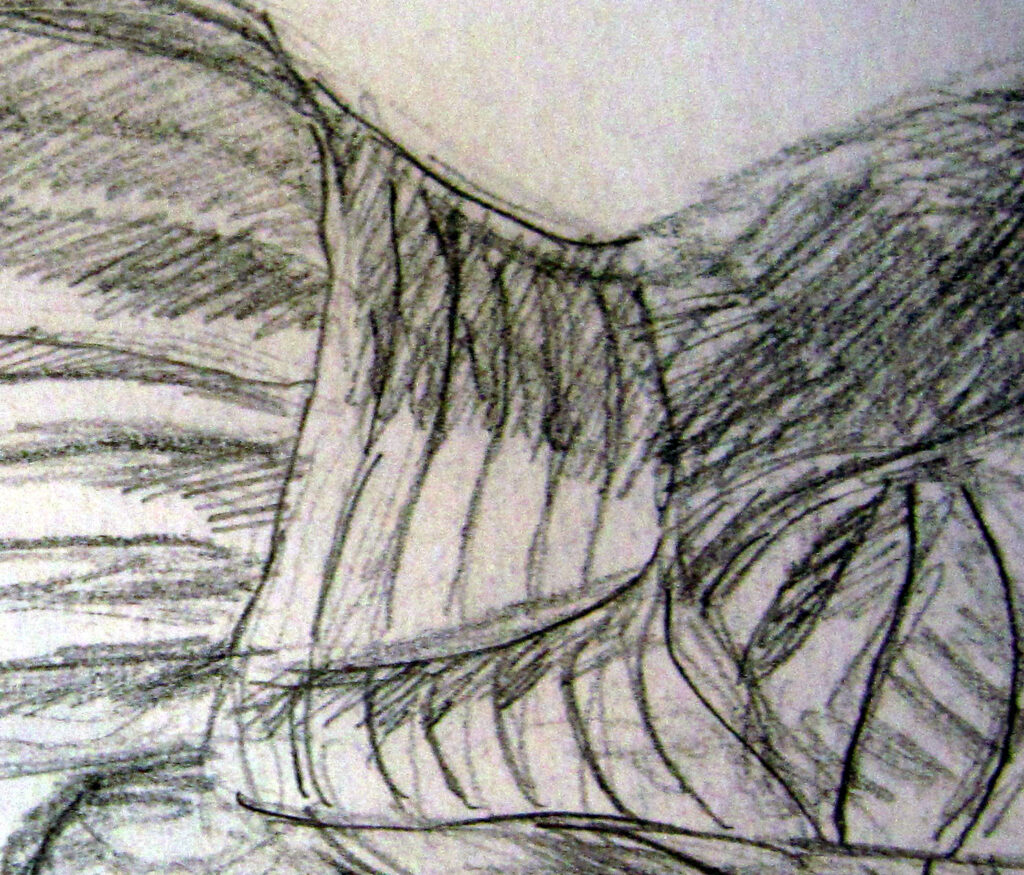

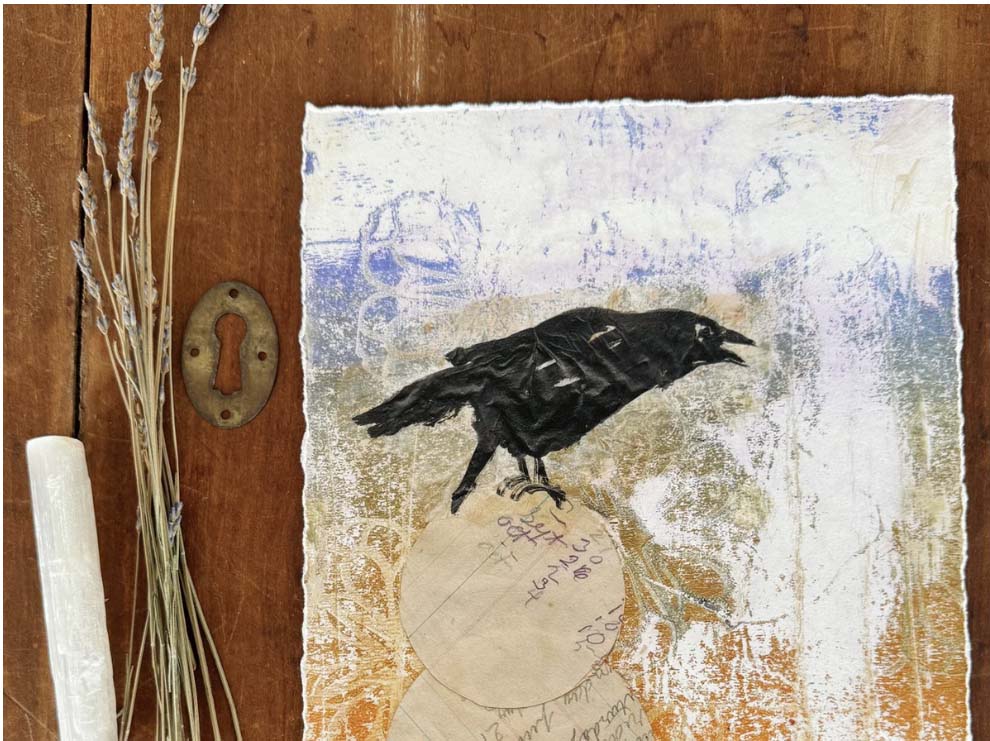

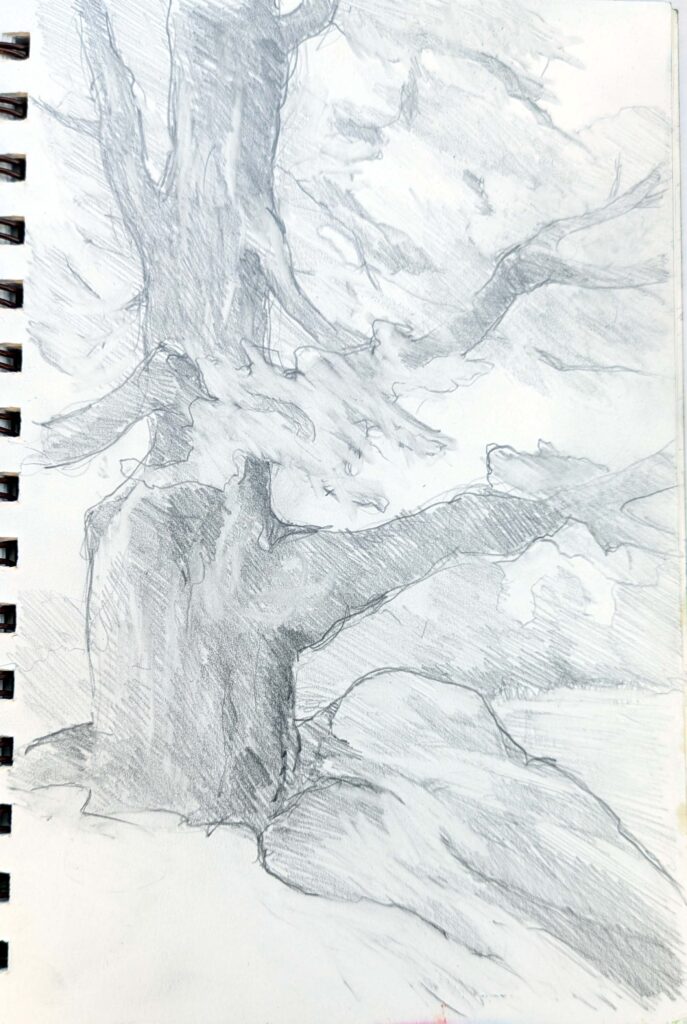

The key lies somewhere in our muscle memory, because drawing instead of writing results in even better memory retention. It doesn’t matter if what we’re drawing is ‘relevant’ or whether the pictures are objectively good.

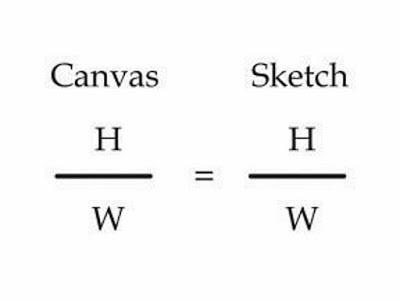

Doodling and drawing (which I would classify as forms of active daydreaming) are means of bypassing conscious thinking. There are times when I’m drawing and listening and need to think out measurement, anatomy or perspective. However, I never tune out what’s being said.

Doodling is said to be a form of fidgeting. It’s less obnoxious than what I’d do without a sketchbook: whisper to my neighbor, tap my knee, or make faces at the kid in the next row. Even at 66, I’m not very good at sitting still.

Why did the benefits of doodling go unrecognized for so long?

I had two high school painting students in the same year. M. was a stellar student and his teachers never minded him drawing in class. S. was, sadly, much more like me: a poster child for ADHD. He got in trouble for doodling. He needed the outlet and was perversely denied it because of his attention problems. To his teachers, he seemed inattentive or bored.

Doodling can be seen as a distraction. Teachers, like everyone else, have personal styles, and some prefer tightly-structured classrooms. Educators, so sorely-pressed to meet top-down academic standards, may think doodling undermines those objectives.

Embrace the benefits of doodling

My son-in-law recently thanked me for letting him know that “you’re allowed to draw in church as long as you’re an artist.”

I reminded him that an artist is someone who makes art, so by definition every doodler is an artist. Until the recent past, the definition of ‘artist’ or ‘musician’ was much more fluid, because people had to make their own entertainment, diagrams, and decorations. Is it coincidence that, as we’ve stopped drawing and making our own music, our society has become so anxiety-laden?

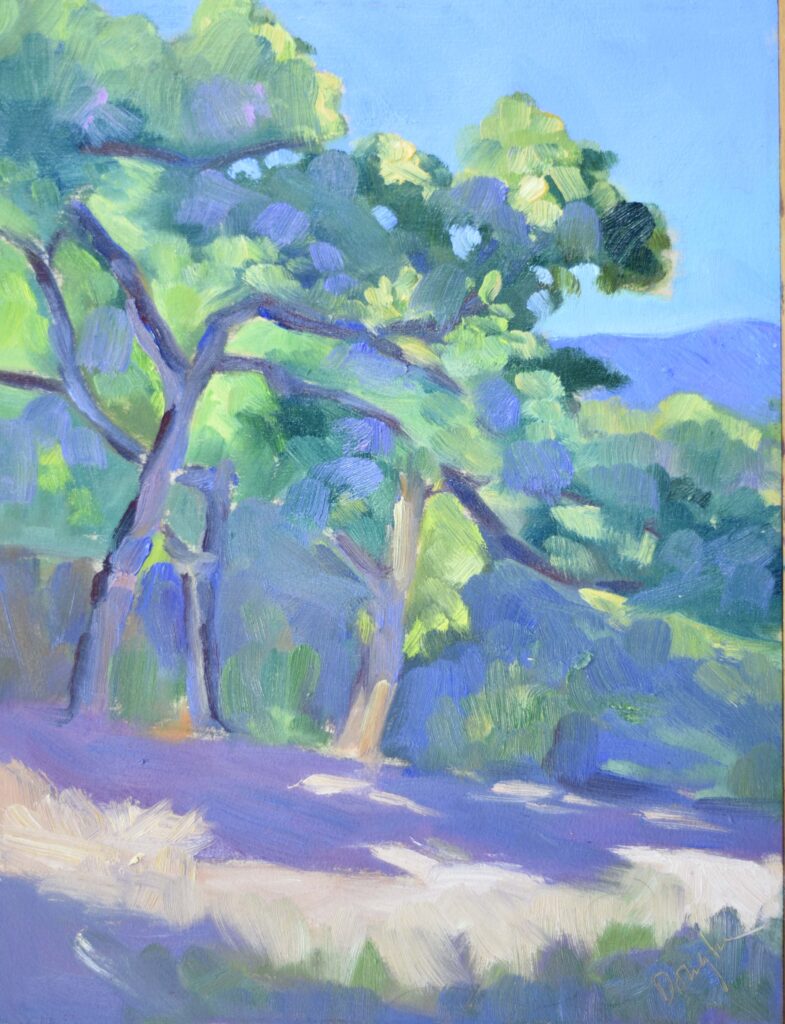

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

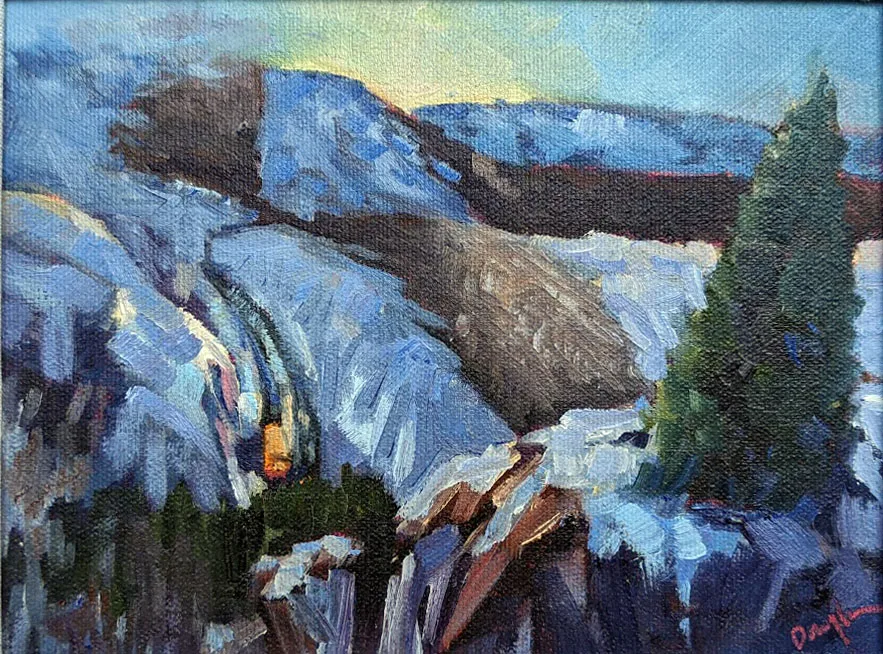

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

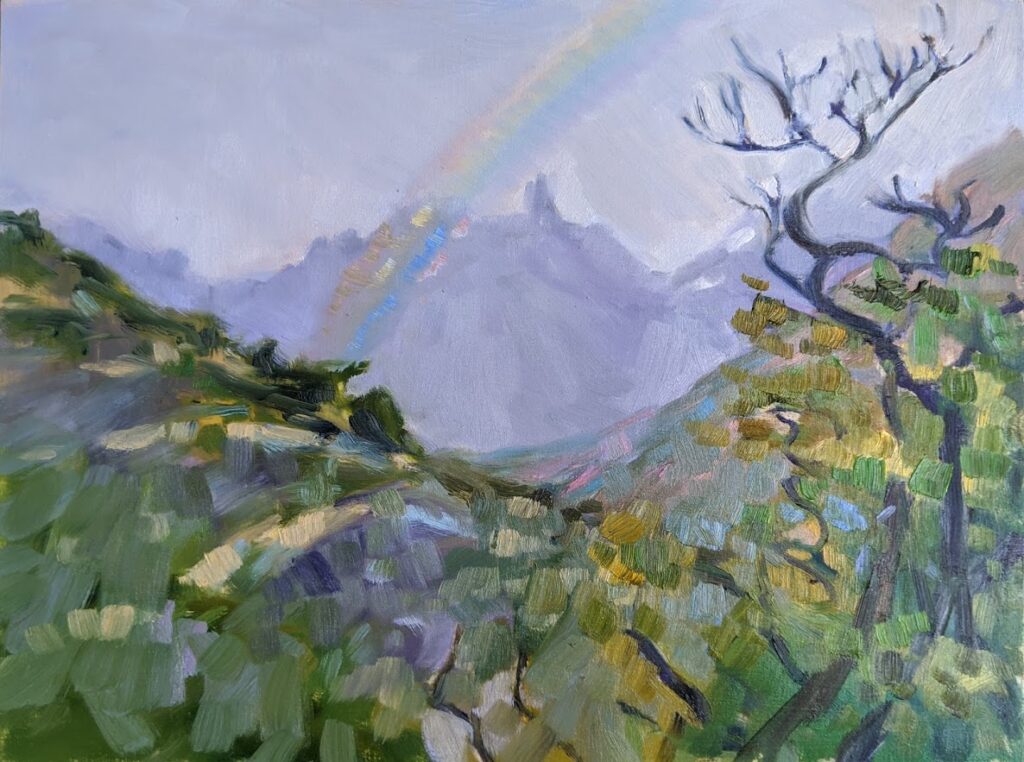

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.