|

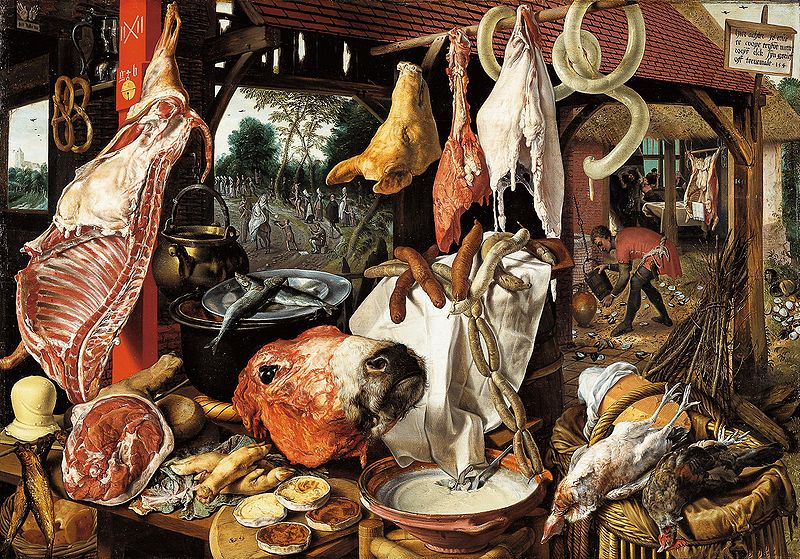

| Butcher’s Stall with the Flight into Egypt, 1551,Pieter Aertsen |

My friend Dan Gowing was writing his Sunday school lesson this week when he realized just how efficient Jesus was with the miracle of the loaves and the fishes. The Gospel of Mark records that there were twelve baskets left after feeding 5,000 men and their families. Dan’s conclusion is that you can’t actually get anything you want from Jesus’ restaurant but you just might find you get what you need.

My holiday motto generally is, “What’s worth doing is worth doing to excess.” In that I am a typical American. Our Thanksgiving dinner alone usually has about twelve baskets of leftovers.

In November, I postedabout Norman Rockwell’s iconic Freedom from Want and how its table is almost bare by modern standards. When Rockwell painted this a mere 70 years ago our self-identity was still Puritan. Today we wallow in outsized appetites, and we’re all pretty fat. In fact, we’re far more like the Dutch Golden Age than our own recent ancestors. Of course, back then the Dutch were rich like us.

On the other hand, most of us miss the point of those Dutch paintings entirely. If we see them just as a celebration of bounty or a cock’s crow of vanity, we’re missing the warning sign buried in them.

Shop, with the Flight into Egypt, top, is in fact an allegory. The Holy Family, inset in a window frame, distributes alms to the poor as they leave. A merry group is seen eating shellfish (a symbol of lust) through the other window. The sign at the top tells you that the land is for sale, leading you to understand that all of this is available at a moral price.

Several cultural forces in the Dutch Republic led to their love of still life. The rise in interest in natural science in the 16th century supported a concurrent rise in realism in painting (trompe l’oeil being the highest expression of this). By the 17th century, the Dutch Republic dominated world trade and had a vast colonial empire. They operated the largest fleet of merchant ships in the world.

But while they were rich and famously religiously tolerant, they were also strictly Calvinist. Icons were forbidden in the Dutch Reformed Protestant Church. Painters were forced to deal with religious subjects through symbolism. Their vanitaspaintings point out the transience of our earthly pleasures.

|

| Flowers in a Silver Vase, 1663, by Willem van Aelst, includes a pocketwatch (time), poppies (death), roses (Christian faith), tulips (folly), dragonfly (transience), and butterfly (resurrection). |

This was particularly easy with flowers. A language of flower symbolism had developed through the Middle Ages. These were both positive (such as the rose and lily representing love in both its divine and human manifestation) and negative (the poppy representing death).

The presence of symbols of impermanence, such as candles, hourglasses, a book with pages turning, or buzzing flies, reminded the viewer that sensory pleasures are ephemeral.

The modern equivalent, of course, is the food photograph. Its similarity is in the excess, but it lacks self-awareness.

Let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in Maine in 2014 or Rochester at any time. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops!