We can smile at a little Russian boy who lived almost 800 years ago, and think of how he reminds us of ourselves at that age.

|

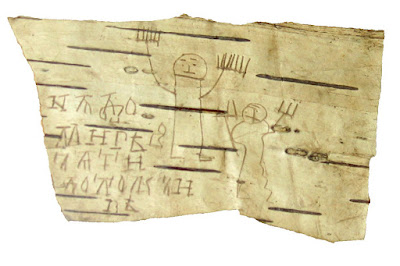

| Drawing by Onfim of Novgorod, c. 1260. All illustrations courtesy of Wikipedia. |

Onfimwas a little boy who lived in the area of Novgorod in the 13th century. What became of him is a mystery, but we know that in 1260, at the age of 6, he dutifully did his homework, and then decorated it with doodles.

Onfim scratched his texts into soft birch bark, which was preserved in the clay soil of the region. These birch bark sheets are called beresty, and there are nearly a thousand of them, dating from 1050 to 1500 AD. The vast majority of them are commercial transactions, legal documents, and Bible verses, but a few give us a glimpse into more ephemeral aspects of medieval Slavonic culture.

|

| In this fragment, Onfim started off copying a Bible verse but got distracted. |

Onfim—like little children everywhere—loved to draw. If you’ve ever spent time with a child of six, you’ll be impressed by two things in Onfim’s scant oeuvre. First, Onfim was almost exactly as literate as a similar child in modern American culture, dutifully writing out his alphabet and simple rote sentences. Second, his drawings are classic, not just in style, but in content. Little boys love action scenes, and Onfim was no exception.

Onfim was drawing in what psychologists call the schematic stage of art development, which is, I presume, how they have estimated his age. He had developed a ‘person’ symbol that was easily recognizable, with a head, trunk and limbs, albeit in very rough proportion. Living in the Middle Ages, he also had a ‘horse’ symbol, just as a modern child might include a ‘car’ symbol. As with many children, he played fast and loose with details, including the number of fingers on his people. For kids, these aren’t important facts.

|

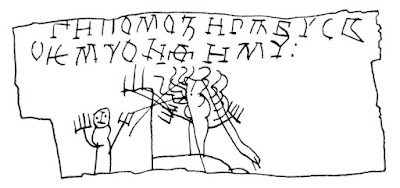

| Gramata 200, by Onfim. |

Gramata 200’s text is an alphabet and Onfim’s name. In the drawing there’s a horse, a weapon, and a defeated enemy. It’s a fantastical drawing of a battle scene. Psychologists say that children of this age can’t think abstractly. However, it’s obvious that they have a great fantasy life.

|

| Gramata 203, by Onfim. |

Gramata 203 also includes a figure on horseback, with either absurdly wavy hair or something else we don’t understand, and another figure standing. The text reads, “Lord, help your servant Onfim.” That’s a conventional medieval statement that may or may not have anything to do with the drawing.

My experience raising kids tells me that their minds don’t generally require much of a connection. Onfim’s teacher may have assigned the text, and then wandered away to do something else, leaving the lad to deface his bark paper. “Oh, Onfim,” his mother may have sighed. “I can’t keep you in beresty. How do you expect to grow up to be a successful trader like your father if you’re constantly doodling on your papers?”

|

| Gramata 199, by Onfim. The reverse is just his schoolwork. |

In Gramata 199, the horse announces, “I am a beast.” Our young artist has added a dedication, “Greetings from Onfim to Daniel.” Were the boys passing notes, or was Onfim just dreaming about getting outside to play with his pal? We’ll never know.

What we can take from Onfim’s doodling is the universal nature of children’s art. The stages children grow through as they mature are integral, rather than learned behavior. Put a pencil in a toddler’s hand and he will scribble with it. Put a pencil in a young boy’s hand today, and he will draw people and cars, or, if he’s raised with them, guns. Children draw what’s in the fantasy space in their heads. While there are cultural overtones to their choices, the fundamentals are constant.

Drawing is a child’s first recorded communication; writing comes later and ultimately supersedes it. Why is that? I suspect that for most children, the transition from fantasy to realism is hard work. But in that first precious burst of artistic expression, we recognize our universal humanity. We can smile at a little Russian boy who lived almost 800 years ago, and think of how he reminds us of ourselves at that age.