Here in the countryside, her subjects love her.

|

| Shop window display in Cumbria |

Every small town we’ve walked through has been decorated for the Jubilee. That’s not with big-box generic décor, either, although there are Jubilee flags and bunting everywhere. Every little shop window and many, many front gardens sport tributes from the heart—handmade signs, memorabilia from the Coronation, and many, many teacups of the kind your grandmother collected.

|

| A laundromat in Haltwhistle, Cumbria |

It's not my country, she’s not my Queen, but the sentiment chokes me up. This is England’s famous red wall, the Labour heartland that went Conservative in the last election. In other words, it’s in political flux. There are both conservative and workingmen’s pubs in these villages, but none of that touches the Jubilee. The Queen truly transcends politics in a way Americans don’t understand. This Jubilee is her celebration.

|

| Every pub is decorated for the Jubilee. |

I am an unabashed fan of the Queen. She reminds me of my mother and all the women of her generation—stoic, composed, hardworking, redoubtable and dignified. I miss them, terribly.

|

| The Jubilee is tied with memories of WW2, which are made more poignant by the current Ukraine war. |

The Washington Post opined recently that the Queen should retire. We Americans are not entitled to an opinion (something we should practice saying regularly about a whole host of things). The British monarchy has had no impact on America for 250 years. Any road, the question of whether she’s ‘fit’ for the role is absurd. The modern monarchy is largely her creation, and for all we know she’ll keep on defining it.

|

| The Queen Bee and her subject bees in Gilsland. |

I will be in Yorkshire for the Jubilee celebrations proper, but there could be no better place to observe them than right here in Brampton, Cumbria—or any of the other little villages we’ve passed through. There will be prayer vigils and parties for the old people. Tomorrow night, there will be beacons lit across England, including along Hadrian’s Wall. These will range from “private bonfires to full-blown spectaculars with fireworks, choirs, pipers, and buglers.”

|

| The Queen's corgis in a large yarn-bomb in Brampton, Cumbria. |

I’ve been to Britain before, but always to big cities or World Heritage Sites. This time, I’m waiting out the rain in country bus stops and drinking in rural pubs. This England is to London as Pecos, NM is to New York. I had breakfast yesterday with a Shropshire farmer. We discussed the labor shortage, just as I might with my Maine neighbor.

|

| In the window of an Indian restaurant in Brampton. |

Two nights ago, we stayed at The Centre of Britain in Haltwhistle. It’s in a stone building that wraps around a 15th century Border Reivers' Pele Tower. It’s ridiculously atmospheric, and it’s for sale for a fraction of the price of a boutique inn in Maine. You’d have to deal with muddy boots, but if you want to throw over your current life for one in a small English village, email the proprietors here. The beer, I promise you, is very, very good.

|

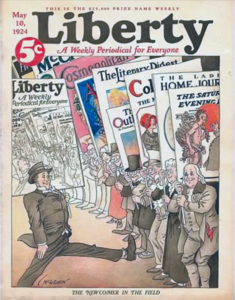

| Many people have pulled out treasured memorabilia from the Coronation in 1952. |