A friend is a friend, and love is love, no matter if it comes by airmail or through the internet, or in person.

|

| My mother and her cousin Gabriel on her last trip to Australia. |

My brother gave me a thumb drive containing about 500 scanned slides from my childhood. They’re very interesting, but they are largely of an era when my parents still only had three children—my sister Ann, my brother John, and, eventually, toddler me.

They went on to have three more—my brothers David, Robert and Daniel. Then John and Ann died in two separate, horrible accidents. My children have only heard stories about them, so their interest is natural. But I could almost not bear the pain of those photos. They’re gripping images of another life entirely, before my family was blown apart by cataclysm. We were miserable for so many years that I’d almost forgotten that we were once happy.

|

| My brother John, me, and my sister Ann kicking up our feet in the Niagara River. |

On the other hand, Doug and I are in Albany with our own four adult children and three grandchildren. They’re nice kids. All of them are productively employed; three of the four are happily married. They love each other enough to want to live in the same city. I understand exactly how blessed I am.

Last year’s blog on this date was called, Joy and tragedy are two sides of the same coin. It was about our first COVID year, but it’s universally true. We lose people we love, and then we gain new people to love. The cycle grows more marked over time, but none of us are immune. Grief is the price we ultimately pay for love.

I have friends who have never escaped the acute phase of grief. I lived there for several decades myself. Faith helps, but it comes with its own questions.

For me, the key to surviving has been to keep my pain in a small box and resolutely look outward and forward. I wasn’t always this way. After my father died, I took on the role of ‘memory keeper.’

|

| Our lovely boat, now long gone, on the wall at Rich Marine in Buffalo. |

Eventually, I realized that I didn’t need to do that. Happiness wasn’t somehow disloyal to the past. If there is omniscience from beyond the grave (and I doubt that, on theological grounds), I don’t think they’d want me to be permanently miserable.

My husband and I don’t exchange Christmas gifts. Now that our kids are grown, there’s seldom anything under our tree. This year, however, I received a package from one of my online students. It contained a cute little ornament that looks just like me. There was also a package marked ‘do not open until Christmas.’ It was squishy and for some reason I decided that it was a stollen.

I was wrong; it was a collection of fine oil-painting brushes from a group of my online students. To say I was speechless, shocked and moved is an understatement. I couldn’t imagine why anyone would give me such a lovely gift. “We call that being ‘surprised with love,’” said the instigator.

I haven’t met all these students ‘in the real world.’ I’m no longer certain that such a distinction even exists. The line between real-world and internet contact is now so blurred as to be almost meaningless.

|

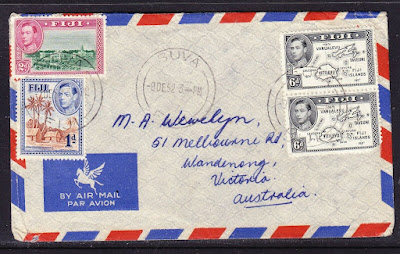

| You young’uns may have never seen an airmail letter. It was a thin, parchment paper and you filled every inch of it with script, because it was expensive to mail. (Courtesy ebay) |

My mother and her cousin-in-law in Australia wrote to each other for five decades, starting in the early 1960s. They never met in person until middle age, but they were always friends; decades of indirect contact forged intimate relationship.

I remember telling my youngest that his online friendships were not ‘real’. I’m afraid I owe him an apology. A friend is a friend, and love is love, no matter if it comes by airmail or through the internet, or in person.

In a few minutes, I’m going to head over to my eldest daughter’s house and play with my grandkids and look resolutely forward and outward. Have a blessed, happy new year, my friends.