Even though this truck and I have only been shacking up for a few months, it feels like we’ve known each other forever. We’re soul mates.

|

| Painting from the bed of my truck yesterday. Note the dog in the back window. (Photo courtesy Eric Jacobsen) |

I’m a little under 5’6”, which is two inches taller than the average American woman (whoever she is). That makes me, objectively, not short. But I married a tall man. Predictably, all my kids are tall. I’m always craning my neck to natter at them, and bustling along when we walk. It’s given me a complex.

It doesn’t help to paint with Ken DeWaard and Eric Jacobsen. Ken’s nearly a foot taller than me, and Eric’s just a smidge less lofty. For me to paint the view they see, I need to stand on a box. That’s inconvenient. Last week, Ken and I painted a pile of glorious orange lobster buoys. His angle was perfect, but mine was obscured by a kid’s slide.

|

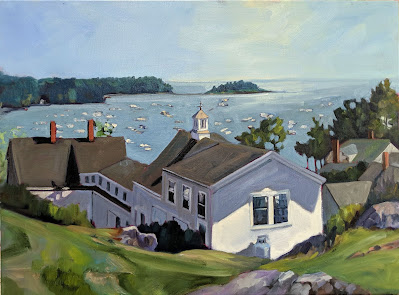

| Three Chimneys, oil on canvasboard, 11X14, $869 unframed, was painted from the bed of my pickup truck this week. |

My trip to Wyoming in January was two-fold. I explored a ranch in Cody that I’ll be using as a base for a workshop this September. And I collected a 2010 Toyota Tundra that previously belonged to my pal Jane Chapin.

This truck and I had a history. Jane and I once nearly drove it off a cliff-edge. We then backed out through a thicket of piñons. It’s only fitting that they’re my scratches now.

I also painted Hermit Peak from its bed. Jane was too cool to paint from a lawn-chair in a pickup truck so she stood in a snowdrift and froze. That day was when I realized that I desperately wanted a pickup truck. It was pure chance that it ended up being the same truck.

|

| Maple, oil on canvasboard, 12X16, $1159 unframed, was painted from next to my truck. I did get stuck in the mud and had to use 4WD to get out. |

Maine has eco-warriors in their hybrids and sensible Subarus, but get out of the bigger towns and pickup trucks abound. I drove a Prius for 278,000 miles and my son now has it. But the pickup truck provides protective coloration when I’m loitering around docks and country roads. Think of me as a toad blending in with the forest floor.

Plus, it makes me feel really, really tall.

|

| All I need is a cooler and an awning. (Photo courtesy of Eric Jacobsen) |

Eric—coincidentally—has the same make and model truck. His has a cap, which is convenient because he never has to put anything away; he just tosses wet paintings inside and they’re there weeks or months later when he feels like finishing them. But the cap means Eric can’t stand in the bed of his truck and paint. That’s a major disadvantage.

Still, they’re awfully cute parked next to each other. We painted at Owls Head this week—me in the bed of my truck, he with his easel set up nearby (making us almost exactly the same height, dammit). It occurred to me that our trucks looked just like cruisers in their little slips in Wilson Harbor. In the evening, yachters would set up their deck chairs, pop beers, and chit-chat across the docks. As a teenager, I sneered. Today, I love the idea.

|

| Fishing shacks at Owls Head, not yet finished. |

“All I need is a cooler and an awning,” I told Eric. A bimini top? It would be cute but expensive. A party tent? A ladder rack with a fabric awning attached with Velcro? Extra points if I can find Sunbrella™ in camo.

But wait, there’s more! The jump seat in the back folds up, and the space it leaves is just the right size for a primitive porta-potty. It might not be quite the thing for downtown Portland, but it works just fine in rural Maine.

|

| A bucket with a toilet seat… and tinted windows. |

Sigh. Even though this truck and I have only been shacking up for a few months, it feels like we’ve known each other forever. We’re soul mates.