Coronavirus has closed McDonalds all over America. That’s tough on the long-distance driver.

|

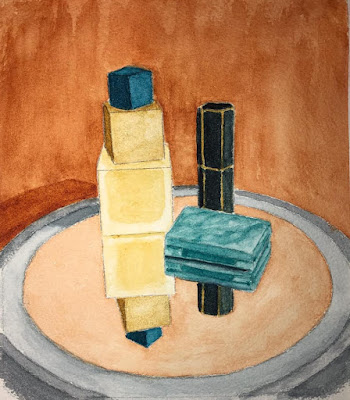

| Wind River Canyon, by Dwight Perot. |

I thought I knew all there was to learn about the pipi sauvage, the business of peeing in open spaces. I’ve managed it on four continents. It’s less of an issue for men, whose clothing is designed for it. Women have to get creative about finding a place to crouch, but it can be done, even on the high plains without so much as a scrub pine in sight.

It’s not that Wyoming doesn’t have beautiful rest stops; they do. But once you leave the interstate, you leave the conveniences behind. For both genders it’s gotten worse with the advent of COVID. McDonalds, that defender of long-distance drivers’ bladder health, has closed its lobbies in many states. It’s the tumbleweed or adult diapers in the age of Coronavirus.

|

| The upthrust east of the Rockies, called High Plains, is beautiful, desolate and windy. Photo by Dwight Perot. |

The pipi problem was just the last in a line of small inconveniences. I never seem to be able to get on a plane and land three hours later, unruffled, at my destination. Perhaps that’s in part because I live 90

Since I left Colorado in the early 80s, Stapleton Airport has been replaced by Denver International Airport. Like everything else on the Front Range, it’s bloated beyond function. It took way too long to cut loose with our bags and rental car. I was exhausted, but I soldiered on through dinner with family, and gratefully went to bed almost 24 hours after I’d risen.

|

| Anticlines make for beautiful painting. Photo by Dwight Perot. |

At 2 AM, I was awakened by a ringing doorbell. I peered out through the window slats and decided it was prudent to ignore. The doorbell rang again, this time accompanied by a maglight. It was a cop. He’d noticed a car door open; had we been burgled? The hoarfrost inside my rental car told the story; I’d just been too tired to close it. They say that exhausted drivers are as impaired as drunk ones, and that’s a warning I should heed.

The development that blights Colorado’s Front Range mercifully ends north of Fort Collins. I found a porta-potty in a city park in Cheyenne and struck northwest towards Cody. That route takes you east of the mountains, but the payoff is a fabulous climb through the Wind River Canyon, surely one of the great beauty spots in America. High plains drifting is not as dramatic as the mountain peaks of Colorado, but just as beautiful. My geologist son and I traced geological strata as we drove. Artists love anticlines because they produce wonderful angles; geologists love them for their oil deposits.

|

| The beautiful Wind River. Photo by Dwight Perot. |

We easterners must hydrate when we get to the Rockies. That unfortunately makes the pipi rustique problem an urgent one. North of Casper, I met my bête noire in the form of gale-force winds. Privacy wasn’t the issue; but peeing in a crouching position was darn near impossible. Men can just aim downwind; as for me, I’ll be doing laundry later today.

|

| Approaching Cody. Photo by Dwight Perot. |

I dumped the rental car in Cody and met up with Jane Chapin, who’d driven down from the ranch to collect us. There’s an amazing 360° mountain view from the ranch-house, and I can’t wait to paint. But first I must slap my plates on the truck I’ve driven out to collect, still scratched from the time we decided it was more prudent to back up through piñon than drive over a cliff. “That’ll buff out,” Jane had said. I’m still laughing about it two years later, and now it’s my truck, not hers. Yes!