If you don’t have technique, nobody’s going to notice your emotional content.

|

| Boating, 1874, by Édouard Manet, courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s beautifully composed, serene and yet energetic. |

In one of my classes, an advanced student (who has probably won more awards than me) asked why I focus on systematic painting. “What about emotion and feeling?” she asked.

Oddly enough, for all that we’re social beings, our souls are insulated. We are born alone, and we die alone. At times in between, the lucky among us carry on conversations with each other or with God. But our emotional intelligence is very personal and private. We can share it if we choose to, but I doubt others can influence it. The best we can do is encourage others to be moral and empathetic.

|

|

Self Portrait at 28, 1500, by Albrecht Dürer, courtesy the Alte Pinakothek. Is it possible to have a crush on a man who’s been dead for 500 years? |

That doesn’t mean I can’t teach students to see and recognize beauty. This is why I often have my students look at and learn to analyze great paintings. I’m a firm believer in the non-linear, associative, synthetic mind, and our sympathetic intelligence. “Think with your gut” is not just an expression. If you’ve ever been truly terrified, you know that only a small part of you is controlled by your rational mind. Beneath that, we run on very primitive lines. The interchange between that and our rational minds is what drives creative expression.

|

| The Census at Bethlehem, 1566, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, courtesy Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. I love how Brueghel always pushes the main action into a corner. Just like life. |

But art—no less so than mathematics—is an intellectual discipline. Most great painters approach the problem in the same way: they make design decisions, color decisions, and lay their paint down in the prescribed manner handed down to us over centuries.

Why do they do that? Because it works.

|

|

Late Afternoon, Monhegan Island, by Rockwell Kent, courtesy Jamie and Phyllis Wyeth Collection. It’s always a toss-up between Lawren Harris and Kent. The light is spectacular, the colors are the essence of sunset. |

System is liberating. If you doubt that, consider the last time you flailed around trying to make a picture and ended up with mush. It happened because you either forgot what you were doing or changed your mind in mid-painting.

I used to write music. It sometimes shocks me to sit down at the piano and realize I no longer can run through chord progressions automatically. How did I ever learn that? By learning lots of music by rote. I read it, I regurgitated it, and occasionally, I managed to be lyrical with it. Now that I’ve forgotten it all, I can’t express any emotion through the keyboard.

|

|

Moonrise, 1894, by David Davies, courtesy National Gallery of Victoria. It’s simple, austere and powerful. |

On the other hand, I’ve painted more than a thousand paintings. Occasionally I surprise myself by being brutally honest, as I was with The Dooryard, painted last week. Its emotional kick wasn’t conscious but it comes from a deep and real place: that’s my darkened bedroom window.

I don’t have to ask myself, “can I do this?” I know the process and I approach a painting the same way every time. Knowing the limits means I know where I can push. I can rise above the technical issues to occasional lyricism.

|

| Haymaking (Les Foins), 1877, Jules Bastien-LePage, courtesy Musée d’Orsay. Exhaustion is something I understand intimately, and he has expressed it so poignantly. |

Does that get stale? Of course not. There is enough mystery in painting to keep me working until I die. Recently, Colin Page told me he was studying John Singer Sargent boat watercolors. Colin certainly knows how to paint, and he has a process that works. But that doesn’t mean he’s stopped searching.

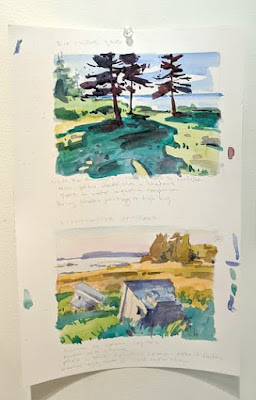

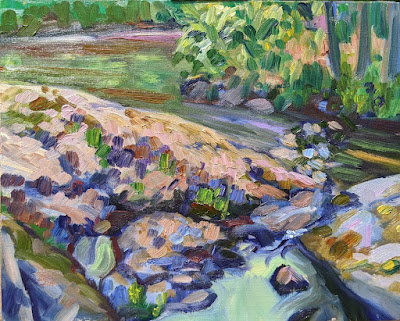

Your assignment is to identify your current five favorite paintings and tell me why you love them. Since I’ve demanded that of you, I gave you mine as illustrations for this post. Don’t get too excited. The list might change tomorrow.