Art has allowed me to look at pain, grief and dislocation obliquely, instead of confronting them head-on.

|

| Carrying the cross, by Carol L. Douglas, courtesy St. Thomas’ Episcopal Church, Rochester, NY. |

You may have noticed that I haven’t done much this week. I finally collapsed from the ailment we dragged back from South America. Despite a slew of tests, no pathogen has yet been identified. However, our nurse-practitioner treated the symptoms. I’m almost back in fighting form, albeit very tired. Hopefully, my fellow travelers will recover as quickly.

Yesterday I attended a virtual meeting. One of my fellows, normally a very cheerful woman, was awash with anxiety. “I can’t paint!” she confessed. “I go in my studio and start, and then I go back and turn on CNN.” Later, I asked her if there was anything I could do to help. She elaborated. Her daughter has had COVID-19; she knows a young person currently on a vent and has lost another friend from it. She—like me—is from New York, the epicenter of this disease. That’s where our kids, friends and family are, and there’s nothing we can do to help them.

My heart goes out to her. It’s an awful thing to feel helpless in the face of disaster.

|

| The Curtain of the Temple was Rent, by Carol L. Douglas, courtesy St. Thomas’ Episcopal Church, Rochester, NY. |

When we were

waiting out our confinement in Buenos Aires, I was thoroughly disinterested in the non-existent landscape. It was not until the end that I decided to start painting what I felt instead of what I saw. That’s not necessarily easy for a realist to do directly (although we’re all doing it indirectly). That’s why I started with the idea of

home, and then moved to Blake’s

Jerusalemfor inspiration. I could look at my feelings of

griefand dislocation obliquely, instead of confronting them head-on.

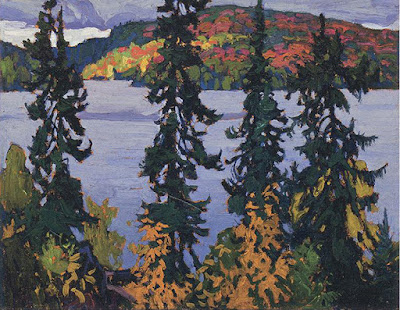

Twenty years ago, I was asked to do a set of

Stations of the Cross for St. Thomas’ Episcopal Church in Rochester, NY. The request was made in the summer; by September I’d been diagnosed with a colon cancer that had perfed the bowel wall and spread to nearby lymph nodes. I had four kids, ages 11 to 3. My primary goal was to stay alive long enough to see them raised.

Finishing an art project seemed almost frivolous in the circumstances. I was especially disinterested in one that dealt with the horrific events leading up to the Crucifixion. That year was a late Easter, too, so by the time Holy Week arrived, I had a rough version finished, which I delivered in book form. (In some ways, I prefer it to the final Stations, for its very rawness.)

|

Veronica, by Carol L. Douglas, courtesy St. Thomas’ Episcopal Church, Rochester, NY. And before you correct me, I’m perfectly aware that Veronica is medieval fan-fic, but I think it points to a very human need to ameliorate suffering.

|

I drew in my hospital bed, from my couch, during the hours of chemotherapy. I wouldn’t have told you I was engaged or enthused in the least. When I was well enough, I arranged a massive photoshoot and took reference photos. The final drawings were finished the following year. They weren’t my best work, I thought, but at least they were done.

And yet, and yet… they’ve been in use for two decades since. And every Holy Week, I get a note from a parishioner telling me how much they appreciate them. I’ve certainly gotten more meaningful mail about them than about any other work of art I’ve ever done.

This year, St. Thomas’—like the rest of Christendom—is shuttered, its people observing the rites from afar. I’m not sure how I’m going to approach Good Friday in a season already penitential in the extreme, but there’s something to be said for routine, ritual, habit and movement. That goes for painting as much as for faith.

May God bless you this weekend with a radical new way of seeing things, in Jesus’ name, amen.