Learn how to draw a pie plate, dish, cup, or vase. I’m throwing in my pie crust recipe, so you can learn to make a pie, too.

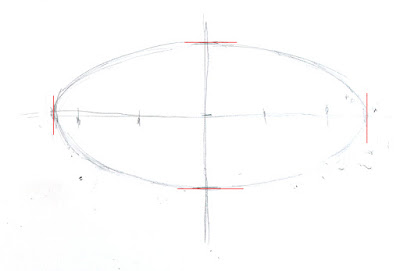

When drawing round objects, we have to look for the ellipses, which are just elongated circles. Ellipses have a horizontal and a vertical axis, and they’re always symmetrical (the same on each side) to these axes.

|

|

The red lines are the ellipse and its vertical and horizontal axes. The two sides of the axes are mirror images of each other, side to side and top to bottom.

|

This is always true. Even when a dish is canted on its side, the rule doesn’t change; it’s just that the axes are no longer vertical or horizontal to the viewer.

|

|

Same axes, just tipped.

|

As always, I started by

taking basic measurements, this time of the ellipse that forms the inside rim of the pie plate. (My measurements won’t match what you see because of lens distortion.)

|

|

This was where I learned that I couldn’t balance a pie plate on the dashboard in my husband’s old minivan.

|

An ellipse isn’t pointed like a football and it isn’t a race-track oval, either.

It’s possible to draw it mathematically, but for sketching purposes, just draw a short flat line at each axis intersection and sketch the curve freehand from there.

|

|

The inside rim of the bowl.

|

There are actually four different ellipses in this pie plate. For each one, I estimate where the horizontal axis and end points will be. The vertical axis is the same for all of them.

|

|

The horizontal axis for the bottom of the pie plate.

|

Next, I find the horizontal axis for the rim, and repeat with that. It’s the same idea over and over. Figure out what the height and width of each ellipse is, and draw a new horizontal axis for that ellipse. Then sketch in that ellipse.

|

|

Three of the four ellipses are in place.

|

Because of perspective, the outer edge of the rim is never on the same exact horizontal axis as the inner edge, but every ellipse is on the same vertical axis. We must observe, experiment, erase and redraw at times. Here all four ellipses are in place. Doesn’t look much like a pie plate yet, but it will.

|

|

Four ellipses stacked on the same vertical axis.

|

If I’d wanted, I could have divided the edge of the dish by quartering it with lines. I could have then drawn smaller and smaller units and gotten the fluted edges exactly proportional. But that isn’t important right now. Instead, I lightly sketched a few crossed lines to help me get the fluting about right. It’s starting to look a little more like a pie plate.

|

|

The suggestion of rays to set the fluted edges.

|

Now that you’ve tried this with a pie plate, you can practice with a bowl, a vase, a wine glass, or any other glass vessel.

|

|

Voila! A pie plate!

|

Meanwhile, here’s my pie-crust recipe. Nobody in their right mind would ask me to cook, but I can bake.

Double Pie Crust

2.5 cups all-purpose white flour, plus extra to roll out the crusts

2 tablespoons sugar

1 ¼ teaspoon salt

12 tablespoons lard, slightly above refrigerator temperature, cut into ½” cubes.

8 tablespoons butter, slightly above refrigerator temperature, cut into ½” cubes.

7 teaspoons ice water

Thoroughly blend the dry ingredients. (I use a food processor, but the process is the same if you’re

cutting the fat in by hand.) Cut in the shortening (lard and butter) with either a

pastry blender or by pulsing your food processor with the metal blade. It’s ready when it is the consistency of coarse corn meal. (If it’s smooth, you’ve overblended.) Sprinkle ice water over the top, then mix by hand until you can form a ball of dough. If the dough seems excessively dry, you can add another teaspoon of ice water, but don’t go nuts.

Divide that ball in two and flatten into disks. Wrap each disk in wax paper, toss the wrapped disks into a sealed container and refrigerate until you’re ready to use them.

Don’t worry if the dough appears to be incompletely mixed or the ball isn’t completely smooth; mine comes out best when it looks like bad skin.

Let the dough warm just slightly before you start to roll it out. And while you don’t want to smother the dough with flour when rolling, you need enough on both the top and the bottom of the crust that it doesn’t stick. If you’re doing this right, you should be able to roll the crust right up onto your rolling pin and unroll it into your pie plate with a neat flourish.

(If you’ve never rolled out a pie crust,

watch this.)

I use this crust for single- or double-crusted, fruit and savory pies.