I have an opening in Tenants Harbor and am teaching a free modeling class in Camden. If you still miss me after that, it’s your own darn fault!

|

| Glade, by Carol L. Douglas, watercolor on Yupo paper |

There will be wine

I’m setting up right now for an opening next weekend, September 7, from 5 to 7 PM. This is a duo show with Midge Colemanat the Jackson Memorial Library in Tenants Harbor, ME. I’ll be showing work I did last September at the Joseph Fiore Art Center. These are eight sets of large paintings. One is in watercolor, its mate is in oils, and each pair is of the same subject. They address the question of how working in alternating media, back-to-back, would influence an oil painter. A year later, I have the answer, which I’ll share with you on Saturday evening.

This is the first time they’ll be shown as an integrated set, and the first time I’ve shown watercolors in a serious way. Students are sometimes surprised that I teach watercolor, but it’s a delightful medium that I’ve been painting in since I was very young. Watercolor has the advantage of being very portable and light.

| Round Pond, by Carol L. Douglas, oil on canvas |

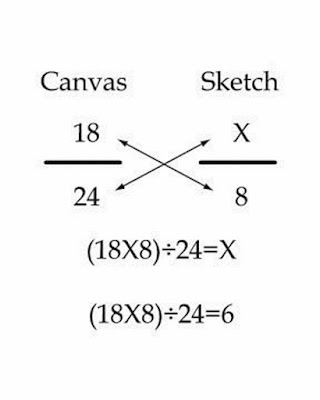

That isn’t true of these paintings. The size was dictated by a watercolor full sheet, so both the oils and watercolors are 24X36” in dimension.

The Jackson Memorial Library is a gem—a perfect place to display artwork. It’s a new building set close to the school so that kids can walk a short distance through the woods for their library classes. It was tailor-made to be a great art space.

Saturday, September 7, 5-7 PM

Jackson Memorial Library

71 Main Street

Tenants Harbor, ME 04860

Jackson Memorial Library

71 Main Street

Tenants Harbor, ME 04860

|

| Michelle reading, by Carol L. Douglas, oil on canvas |

You should be in the pictures!

Earlier, I’ll be teaching a free introduction to figure drawing for models and artists, offered by the Knox County Art Society at the Camden Lions Club. If you’ve ever toyed with the idea of being a figure model but are unsure about what it entails, this is for you. Artists get the free benefit of being there to draw along.

I’m an experienced figure teacher, but this is first time I’ve ever taught models how to strut their stuff. I’m working with an experienced figure model. She will demonstrate short, medium, and long poses. Prospective student models don’t have to doff their clothing for this session.

Artists interested in sampling a life drawing session are also invited to attend, to both observe the instruction and to draw.

I’ll be covering the history, practice and protocols of nude modeling; gestural/athletic poses; reclining, crouching, bending, standing poses; changing direction; considerations of negative space; torso twisting; working with the lighting; positioning of limbs; facial expressions; using props; and incorporating fabric folds.

|

| Couple, by Carol L. Douglas, oil on canvas |

If they wish, students completing the session will be considered for paid modeling assignments for Camden Life Drawing.

The session runs from 9:30 to noon and is free to all; the suggested donation for artists is $10. Advance registration is requested. Contact David Blanchard, 207-236-6468.

Saturday, September 7, 9:30 AM to noon

Camden Lions Clubhouse

10 Lions Lane

Camden, ME 04843

Camden Lions Clubhouse

10 Lions Lane

Camden, ME 04843