Judging art is very subjective. You can’t take the results personally, or the process will chew you up.

|

| Tom Sawyer’s Fence, by Carol L. Douglas |

This weekend, a reader asked for help in choosing slides to apply to her first plein air event. She recognizes that her favorites might not be a juror’s favorites. Every artist feels like he or she could be better at this, including me. I’ll share what I’ve observed, but I’d welcome your input.

Apply for shows that match your level of experience. Think of these events like applying to college: there are dream, target and safety schools. Later on, you can throw money away applying to dream schools, but for your first event, a safety or target school is a smarter choice. How can you tell what level the event is geared to? Look at the prize money. The bigger the prize money, the fiercer the competition to get in.

Look at last year’s participants. Are they painting at a level you feel comfortable challenging? If not, find a different event to start with. There are many of them out there, and you’ll have a much better experience if you’re not thrown at the first hurdle.

|

| Parrsboro Sunrise won a prize but I can’t seem to make it photograph well. |

Take good photos of your work. One of my best paintings from 2018 won’t be in my submissions because I don’t have a decent photo of it—it was gone before I got a color-balanced picture. It’s very difficult to take a good photo of a very wet oil painting in the back of your car, but try your best. The photo should meet the minimum pixel requirements of the application. If all you have is a low-res cell phone photo, send something else.

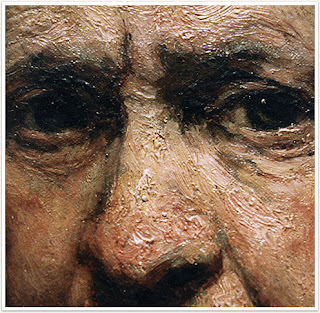

I did a few paintings in 2018 on very smooth boards, just to experiment. One of them won a prize at

PIPAF, so the board has nothing to apologize for, but it has no tooth. That meant that my paintings have little impasto, and that in turn makes them look out-of-focus in photos. It’s maddening, because they’re beautiful in life, just not so nice in the digital world.

|

| Jonathan Submarining apparently made me happier than it made anyone else (except Jonathan’s grandmother, who bought the painting). |

Ask a trusted friend to look over your submissions. I have a painting from a few years ago that I adore, Jonathan Submarining. It was of a bunch of kids in a sailing lesson on a riotous day, and it was painted very fast, standing in the tide, with a fierce wind threatening to knock over my easel. But nobody scanning hundreds of photos will ever know what was involved in getting that painting right.

It took a disinterested friend to point that out to me. Sometimes, we’re the worst judges of our own work. We see the struggle instead of the finished product.

|

| Santa Fe Sunset, by Carol L. Douglas. |

Look at your work as thumbnails first. If a juror has a hundred applicants and has to look at five slides each, that may be all they ever see of your work—unless something about it really stands out to them.

Familiarize yourself with the entry juror, if that information is public. I’m not saying you should paint like him, but you ought to understand what’s important in his work. If every painting he does is carefully drafted and includes buildings and canyon walls, don’t send three structure-free marsh paintings and expect to be his favorite. If he’s a luminist, he’ll respond to light, and if he’s a brilliant compositor, he’ll respond to design.

Even so, I think it’s a mistake to pitch too closely to the entry juror. A lot of shows don’t identify the entry juror at all. Some use a committee. In any case, try to mix it up. If you can handle radically different subjects well, you demonstrate your versatility and your drawing chops.

|

| Best Buds is a favorite from my 2018 season. While it was within the parameters of the show it was done in, it wasn’t actually done outdoors, so I won’t be using it for my slides. |

Consider the order of your images. Online jurying systems allow you to define the order in which slides are viewed. If the entry juror is looking at your slides in sets, he’s going to read them left to right, just as he reads text. Make the first and last images particularly compelling—the first one to catch his interest and the last one so you’re remembered.

For heaven’s sake, don’t cheat. There are all kinds of carefully formulated ‘rules’ about what constitutes plein air, and most of them are hot air. But if you didn’t do the painting outdoors, on location, don’t include it among your slides.

Don’t feel bad if you don’t get in, even if you’re a much better painter than some of the people who did. There are often factors involved in jurying that you don’t know about, such as a need to have more watercolorists, or geographical representation. Or, the juror just woke up hating sunsets that morning. Judging art is a very subjective experience and you can’t take the results personally, or the process will chew you up.