It’s just like a job search.

|

| Yes, gallery representation is an attainable goal. |

“I guess I really don’t know how to get gallery representation,” an experienced artist told me. “I tried a couple times, unsuccessfully.” As with a job search, you have to try many times before you get there.

There are no shortcuts.

Make sure your website is up-to-date. It should include your newest work, dimensions, media, and, optionally, prices. A neat, easily-navigated portfolio of photographic images, including current curriculum vitae (CV), is good to have in reserve, but don’t plan on taking it around and sticking it in gallerists’ faces. Instead, introduce yourself, hand the gallerist your card, and follow up with an email.

Don’t assume you have to talk to the top dog. A good gallerist trusts his or her assistants’ judgment.

Do your research. If you’re mass-mailing enquiries, you’re doing it all wrong. At a minimum, you should have visited all the galleries in an area before you approach even one.

Don’t approach a top gallery if you’re an emerging artist. It’s a waste of time. Be sure you like the galleries you approach. While there are often vast differences in style, there are always commonalities, too. Visualize your work on their walls. Are you a good fit?

When you write, direct gallerists to an online portfolio—either your website or one you made especially for them. Always include a current curriculum vitae (CV). Ask the gallerist to review your work against their future needs. Talk about your experience and why you think you’re a good fit. And remember—there are lots of candidates out there. Rejection may have nothing to do with your skills; the gallery may simply be overloaded.

|

| Doing this event in Camden Harbor started my relationship with Camden Falls Gallery. (Photo courtesy Howard Gallagher) |

No stealth visits

When I’m scoping out galleries, I make it clear that I’m an artist, not a buyer. I don’t ask to show my work at that visit; I give them a card and follow up with an email if I’m interested.

Misrepresenting yourself is a terrible way to start a new relationship. Many of my best conversations with gallerists have been because I’m an artist.

Respect their time

Never stop to chat when they’re changing their show. They won’t appreciate the interruption. Likewise, don’t interrupt a potential sale, ever. If they say they review portfolios at a specific time, respect that.

|

| Historic Fort Point, by Carol L. Douglas. This painting at another event started my relationship with the Kelpie Gallery. |

Maintain your image on social media

You love Facebook; gallerists do too. Be professional, up-to-date, and informative, and don’t include information that will shoot you in the foot.

Reverse engineer resumes

Identify a few regional artists whose careers you admire. Their CVs are usually on their websites. You can track their progress from local shows to important galleries. This will give you ideas on what paths to follow.

|

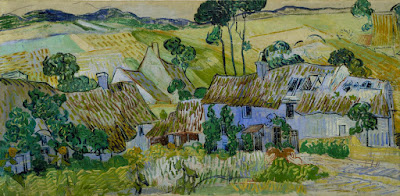

| A Little Bit of Everything, by Carol L. Douglas, oil on canvasboard, long since sold. |

Choose a smart path in

Almost every gallery invitation I’ve received has been the result of an event I did in that community. Gallery owners pay attention to them, especially when they organized the event. If the gallery you’re interested in hosts group shows, apply to them.

I (almost) never turn down an opportunity to show my work, but I know the difference between my local farm and a university gallery. Not every venue is a resume builder.

The studio visit

Should you be lucky enough to net a studio visit, be neat, clean and organized. This is your workspace, and it shouldn’t look like a party house or boudoir. Don’t expect miracles, and don’t try to push the gallerist into taking work he or she doesn’t like.

And, above all, be nice.