We should remember that pinch in the pocketbook when we draw up our supply lists.

|

|

Plastic wrap, by Carol L. Douglas. I can paint without cadmium yellow or cadmium red, but not without cadmium orange.

|

During my absence last week, one of my students took a workshop with another painter, an excellent artist I quite admire. Studying with other teachers is good practice. It reinforces what is essential. And since every teacher has ideas that are simple preference, it helps put those in perspective, too.

Before she went, we spent time talking over the supply list. A student should go into a class with the materials the teacher has requested; otherwise she is hobbled from the beginning. On the other hand, I have had too much experience to not be skeptical of supply lists, which often include everything but the kitchen sink.

True to form, she came back with three or four unopened tubes of paint. I really wish teachers would stop doing that. It’s expensive and its irresponsible.

|

| Teachers should strive to help students navigate through color space. This was a class exercise by Jennifer Johnson. |

I moved a tube of Cadmium Green around for years. It currently lists at $24.95 for 37 ml. It’s a great color for the sallow greens in skin tones, but an effect that can easily be approximated with black and yellow. I was painfully poor the year I took that class, but we never touched the tube.

I’ve come to feel the same way about Cerulean Blue in oil painting. It’s a heavy, dense blue that sells for $34.95 for 37 ml. I learned to paint skies with it, and there is nothing more luscious. Still, skies can be painted quite adequately with Ultramarine or Prussian Blue, which cost exactly a third of what Cerulean costs.

However, because it’s dense and opaque, Cerulean Blue occupies a niche in watercolor that can’t be easily filled by other pigments; hence it stays on my watercolor palette.

|

| Cobalt violet is beautiful but hardly indispensable. |

Cobalt Violet is another very pricey pigment that can be approximated at a fraction of the cost. Note that I said “approximated,” rather than mixed. You can’t mix a respectable Cerulean Blue or Cobalt Violet hue. (For an explanation of hues and other arcana of paint tubes,

see here.) You can only learn ways to paint with less expensive pigments. When possible, that should be the starting point for the teacher. Let your students shop for their Cadillacs on their own.

Our responsibility is more than just financial. We have a duty to train up new artists in safe, environmentally-friendly techniques. All three of the colors I mentioned above are toxic inorganic pigments. They’re harmless as paint, unless you eat or bathe in the stuff. The problem lies in their manufacture (and, to a lesser extent, their disposal). There’s only one plant currently making cadmium pigments in the US, under our strict environmental and worker-safety controls. That means the pigments in your paint are probably coming from offshore, and we have no idea if the process is safe or not.

It’s nearly impossible to clear all the inorganic pigments off our paint-tray, but we can minimize their use. My palette still contains cadmium orange, I’m afraid, because I’ve never found an analog that answers.

|

| Part of my goal is to teach people to mix colors rather than buy them. |

Then there is the question of substrates. Most beginning students are fine with cheap boards, with the caveat that once they start selling work, they need to move up to an archival-quality board. The problem is in the backing, and that’s an issue for future conservators, not for painting class. When I was a student, we worked as often on gessoed paper as on canvases. There is absolutely no reason to make your students buy archival boards for value exercises.

The exception to this is in watercolor and pastel. In both cases, the substrate is as important as the pigment. But even here, one can buy decent-quality student products.

The flip side of this is the teacher who’s afraid to tell his or her students what to buy at all. I find it’s helpful to just list what you carry and work from there, being mindful that some things are just preference, not necessities. Be specific—if you want sanded pastel paper, specify that, for example. But don’t be so specific as to be restrictive. If a student is using a phthalo blue, there’s no point in having him replace it with Prussian blue. They function in the same niche.

Here are my supply lists:

I’m happy to share them with painting students and as a template for teachers to create their own supply lists, but please don’t copy them without credit!

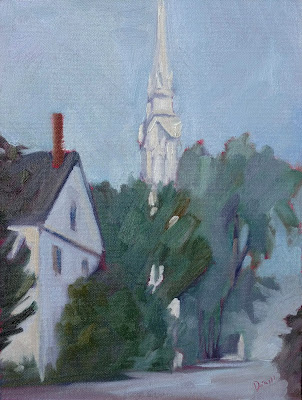

I’ve got one more workshop available this summer. Join me for Sea and Sky at Schoodic, August 5-10. We’re strictly limited to twelve, but there are still seats open.