Time to ditch Daylight Savings Time, and move Maine to the Atlantic Time Zone

|

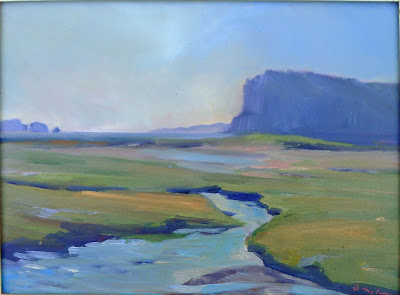

| Marsh with running tide, Carol L. Douglas. These are my finished paintings from Parrsboro. |

Crossing into New Brunswick, the Mainer goes from the Eastern Time Zone to the Atlantic. There’s one more time zone to the east on our continent, the little-known Newfoundland Time Zone, which is staggered on the half-hour. This is followed only on Newfoundland, its offshore islands, and the most southern parts of Labrador.

As weird as that is, it’s no weirder than the sprawling Eastern time zone, which starts somewhere around Grande-Rivière, Quebec, and runs to Ontonagon, Michigan. Sunrise in Grande-Rivière was at 4:17 AM this morning. It was at 6:03 AM in Ontonagon. That’s an unwieldy span.

|

| Headlands, Carol L. Douglas |

Our pre-clock ancestors marked the time of day by measuring with a sundial, making noon whatever time the sun was directly overhead. They weren’t worried that this was slightly different down the road. After all, if you walked from Winchester to Canterbury, any difference in the time would be lost along the way.

Greenwich Mean Time was established to aid navigators to determine longitude at sea. Nobody changed their clocks to match it; they just carried on with solar time right up to the 19th century.

|

| Breaking Dawn, Carol L. Douglas |

Enter the railroads. It was a bit difficult to set a schedule when towns fifteen minutes apart by train used different time systems. By the middle of the 19th century, British rail companies were using Greenwich Mean Time and portable chronometers to standardize time keeping in Britain, although it was a tough sell in places. British clocks from this period sometimes had two minute hands, one for railroad time, and one for local time. But by 1880, Greenwich Mean Time was the standard for Great Britain.

|

| Low tide, Carol L. Douglas |

Here, time was confused in a uniquely American way. Every railroad company had its own standard time, based on where it was headquartered. Its schedules were printed in its own system, leaving the stationmaster at an important junction with the unenviable task of translating several different train lines’ timetables into local time. The solution was multiple clocks, one for each railroad.

Standardization was reached on Sunday, November 18, 1883, known as “The Day of Two Noons,” when each railroad station clock was reset as it reached the standard-time noon. The western limit of Eastern Standard Time was my home town of Buffalo, NY. That’s more than 700 miles east of the current western boundary.

|

| Fox River School, Carol L. Douglas. |

Last fall, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

issued a report recommending that their state ditch Eastern Standard Time “under certain circumstances.” Effectively, it would get rid of Daylight Savings Time—hurrah—and put Massachusetts on Atlantic Time year round.

|

| My quick-draw of Parrsboro and its mudflats. |

I’m all for ditching Daylight Savings Time nationwide. It’s a meaningless exercise that throws our internal clocks off twice a year. I’m also in favor of switching Maine to Atlantic Time. The sun rises 25 minutes earlier in Halifax than it does here. That puts our internal rhythms more in tune with the Maritime provinces than with Michigan.

The problems of such a switch are overstated. If we can do business with Californians and Australians, we can probably figure out the time difference with New York.

|

| A kindly carpenter made teepees for Cathy LaChance and me. Only in Canada! |

It gets dark mighty early here in the winter—Boston’s earliest nightfall is just 27 minutes later than in Anchorage. Since I live 185 miles north and east of Boston, it’s even worse here. Correspondingly, it gets light awfully early in the summer as well.

Have mercy on us, legislators, and let us get some rest.

Just one more workshop this calendar year, but it’s an awesome one! Sea and Sky at Schoodic, August 5-10. Be there or be square.