A new dating technique calls into question what it means to be ‘human’.

|

The ladder-shaped figure dates back at least 65,000 years, making it Neanderthal in origin. Courtesy P. Saura, Science.

|

The first recognized artists in the western canon are Bezalel and his assistant, Aholiab, who

decorated the Tabernacle sometime between 1400 and 500 BCE, depending on who’s dating the book of Exodus. Polygnotus of Thasos, who worked in the mid 5th century BC, was a superstar in ancient Greece, as was his student Pheidias. But of their actual work we know nothing except copies and descriptions.

The oldest extant western art is all anonymous, the work of early Homo sapiens. Our ancestors, after all, have been scrawling on walls for at least 80,000 years. Why they did this, we don’t know, but we do know that art-making is a uniquely human activity, linked to our higher reasoning skills.

|

|

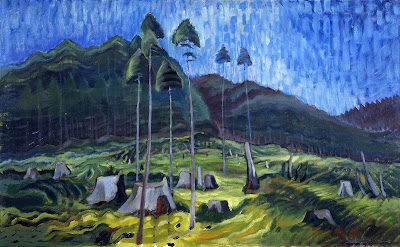

Snowbound, 1911, Charles R. Knight. This is our traditional understanding of Neanderthal culture.

|

Our slower-witted cousins, the Neanderthals, didn’t have those skills, and thus didn’t create and embrace culture as did Homo sapiens. For that and anatomical reasons, we call them

archaic humans, implying that they weren’t quite up to Homo sapiens’ standards. In fact,

Carl Linnaeus used the word

sapiens because it means ‘wise’.

Or that’s what anthropologists thought until recently. A study

published in Science this past February indicates that Neanderthals weren’t nearly as low-brow as we thought. They too created art.

We know that in Africa, Homo sapiens adorned their bodies with pigments and wore beads. There’s some indication that Neanderthals in Europe did the same thing, but anthropologists have always assumed this was something they borrowed from Homo sapiens as the latter arrived in Europe.

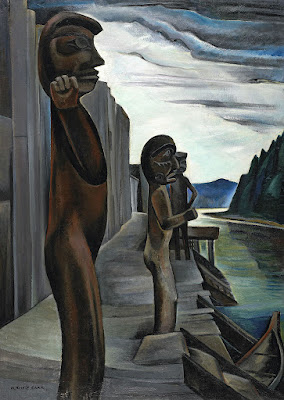

Cave art is a step up in the decorative arts, just as painting is a step up from applying makeup. We’ve always assumed that the cave art seen in Europe was the work of recently arrived Homo sapiens. Of course, that was guesswork, since the art can’t be accurately radiocarbon dated.

Radiocarbon dating is useless for mineral-based pigments. Even when our ancestors were using something organic—like charcoal—contamination issues and sample destruction made radiocarbon dating nearly impossible.

Researchers turned to the mineral deposits that form in caves, called speleothems. Stalagmites and stalactites are the most visible examples, but deposits form in all caves. These can be dated by measuring the natural decay of trace amounts of uranium. This is called

uranium-thoriumdating.

Speleothems form over the surface of cave paintings just as they do everywhere else. Researchers realized that these can give us a latest-possible date without affecting the artwork itself. “In

La Pasiega, in northern Spain, we showed that a red linear motif is older than 64,800 years. In

Ardales, in southern Spain, various red painted stalagmite formations date to different episodes of painting, including one between 45,300 and 48,700 years ago, and another before 65,500 years ago. In

Maltravieso, in western central Spain, we showed a red hand stencil is older than 66,700 years,”

wroteChris Standish and Alistair Pike.

|

| Neanderthal tools |

“[T]he types of paintings produced (red lines, dots, and hand stencils) are also found in caves elsewhere in Europe, so it would not be surprising if some of these were made by Neanderthals, too,” wrote the authors.

According to our current understanding, Neanderthals lived in Eurasia from 250,000 to 40,000 years ago, disappearing about 5000 years after the arrival of Homo sapiens. We first assumed they were made extinct by Homo sapiens’ superior culture; we now believe they were absorbed into the surviving population. That makes more sense if we consider that they had the same capacity for symbolic thinking as their African cousins. We now know that Neanderthals made tools,

built structures, used fire, made art, and buried their dead. In short, they were every bit as human as Homo sapiens.