At an age when modern kids are munching on Tide Pods, Abbie Burgess ran a lighthouse on a rock in the sea.

|

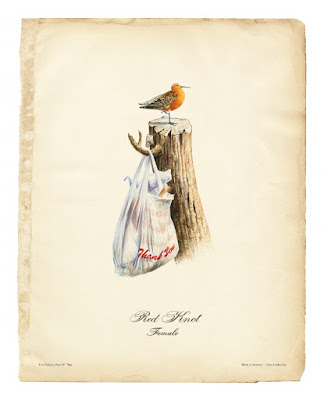

| A 19th century engraving of the girl lighthouse keeper. Courtesy Elinor DeWire Collection. |

Matinicus Rock is a treeless, windswept outcropping of about 30 acres. It’s about twenty miles off the mainland, but it’s on the approach to Penobscot Bay.

Its first keeper lasted four years before going ashore to die. The second keeper also died after a short tenure. A tremendous storm in January 1839 forced a total reconstruction. Keeper Samuel Abbott was forced to take refuge in the attic with his family during the storm of February, 1842. He thought they were all going to die.

Samuel Burgess, was appointed the light’s keeper in 1853. He moved to the lighthouse with his wife Thankful and four of their children. Abbie was the oldest girl there.

|

|

Courtesy Elinor DeWire Collection.

|

She ran the light, freeing her father and brother to fish for lobster. The lamps used lard oil. “[T]hey were more difficult to tend than these lamps are, and sometimes they would not burn so well when first lighted, especially in cold weather when the oil got cold,” she wrote.

Abbe worried that, in the case of a great storm, she would be unable to move her invalid mother to safety. In December, 1855, she moved her mother’s bedroom to the lighthouse itself.

The cutter that was supposed to have supplied them in September had never shown up. By January, food and lamp oil were running low. Samuel Burgess sailed to Rockland for supplies. Shortly thereafter, a Nor’easter blew up.

|

|

Matinicus Light House. Designed by Alexander Parris, drawn by Brown and Hastings, engineers, March 28, 1848.

|

“…Father was away. Early in the day, as the tide arose, the sea made a complete breach over the rock, washing every movable thing away, and of the old dwelling not one stone was left upon another. The new dwelling was flooded, and the windows had to be secured to prevent the violence of the spray from breaking them in. As the tide came, the sea rose higher and higher, till the only endurable places were the lighttowers. If they stood we were saved, otherwise our fate was only too certain.

“But for some reason, I know not why, I had no misgivings, and went on with my work as usual. For four weeks, owing to rough weather, no landing could be effected on the rock. During this time we were without the assistance of any male members of our family. Though at times greatly exhausted with my labors, not once did the lights fail. Under God I was able to perform all my accustomed duties as well as my father’s.

“You know the hens were our only companions… I said to mother: ‘I must try to save them.’ She advised me not to attempt it. The thought, however, of parting with them without an effort was not to be endured, so seizing a basket, I ran out a few yards after the rollers had passed and the sea fell off a little, with the water knee deep, to the coop, and rescued all but one. It was the work of a moment, and I was back in the house with the door fastened, but I was none too quick, for at that instant my little sister, standing at the window, exclaimed: “Oh, look! look there! the worst sea is coming.”

That wave swept the old house off the rock.

The chickens proved their salvation. The Burgesses survived on a daily ration of a cup of cornmeal and an egg for the next three weeks.

|

| Abbie Burgess Grant |

Samuel Burgess lost his job after the election of 1860. He was replaced by Capt. John Grant. Abbie stayed on to train Grant and ended up marrying his youngest son, Isaac. They tended the Matinicus Rock Light for fourteen years, having four sons while there. They then moved to

Whitehead Light off St. George.

Abbie Burgess Grant died in 1892 at the age of 53. “Sometimes I think the time is not far distant when I shall climb these lighthouse stairs no more,” she wrote. “I wonder if the care of the lighthouse will follow my soul after it has left this worn out body!”