When my friend Susie arrived at the farm where we’d agreed to meet, she raised her arms and said, “Paradise!” It was a lovely farm alright, but Paradise?

We wandered. We looked at bales of hay in a pole barn and hiked to a rise where we could look down on the dairy barns. (Marilyn and Susie had previously met the farmer.) This was indeed a well-run and beautiful farm, set in a gently sloping valley.

I asked them why they liked this place. Susie said she was enthralled by the colors and the roll of the land. Marilyn said she saw the human figure in the sinuous twists of the hills.

The Bristol Hills aren’t breathtaking but they are gently beautiful. Long ranges of blue hills overlap in the distance. I never respond to these hills in their purely natural state. I need to see that slash of pale gold in a faraway upland field to understand the lavender and indigo and green of the woods.

The Kingdom of Heaven is in some ways a cooperative venture between God and man. So is this landscape. No wonder Susie called it “Paradise.”

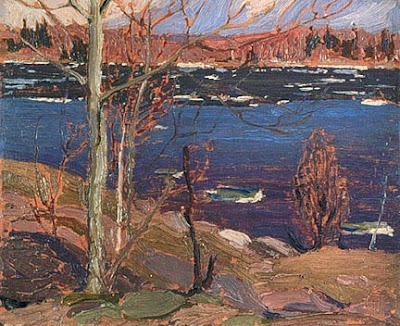

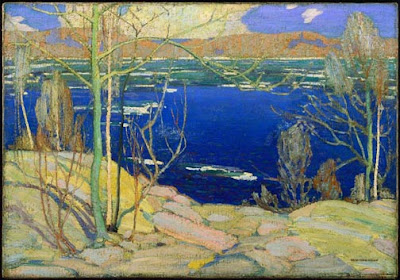

I continue to try to paint in the spirit of the Group of Seven and Tom Thomson. This isn’t really their kind of scene, but the wide disked field presents some of the paint handling issues they addressed. I chose this view for the difficulties presented by that large neutral foreground.

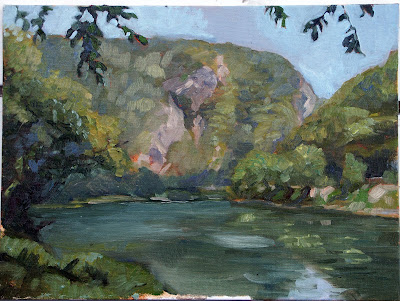

I was working on a 16X20 canvas, a breath of fresh air after all the small studies I’ve done this month. I started with an underpainting in Gamblin’s Transparent Earth Red. You can read more about their transparent Mars colors here.

Although I’ve been trying to work much dryer, the transition from board to untoned canvas makes that a little more difficult. The shadow above the hills is from erasure and isn’t really part of the value study.

Here is the midpoint of my painting. I have decided to do a potentially ugly thing and include the fringe of green at the bottom. As long as the value of the green and the brown are close, I don’t think it will be too awkward-looking.

I still have to unify the sky (yes, there were clouds; they showed up after I started). I have to figure out a paint-handling technique that works for the disked field and make some drawing adjustments on the hill to the right. But, oops! My easel fell and dumped my painting into the ditch.

There are bits of gravel, seeds, and dirt all over the right side of my canvas. The solution is to stop painting, let the surface harden up, and knock the debris loose with a palette knife. Oh, well. I was ready to quit anyway.

BTW, this is my painting buddy Susie:

Ironically, when they aren’t wearing billowing white shirts and off-kilter ball caps (to keep the glare out of their eyes) they are both very elegant women.